The High Water Mark: Gettysburg, A Nation’s Crucible

The summer of 1863 was a season of profound reckoning for the fledgling United States. Four score and seven years after its founding, the nation found itself locked in a brutal civil war, testing whether a government "of the people, by the people, for the people" could long endure. It was against this backdrop of national existentialism that the most famous, and arguably most decisive, battle of the American Civil War unfolded: the Gettysburg Campaign. A collision of titans, a brutal three-day struggle in the rolling hills and farmlands of Pennsylvania, Gettysburg would carve its name into the annals of history as the "High Water Mark of the Confederacy" and forever alter the trajectory of a divided nation.

Lee’s Bold Gambit: From Chancellorsville to Pennsylvania

Fresh from his stunning victory at Chancellorsville in May 1863, where his Army of Northern Virginia had brilliantly outmaneuvered and defeated a Union force twice its size (albeit at the cost of his indispensable corps commander, Stonewall Jackson), General Robert E. Lee felt emboldened. The Confederacy, however, was in a precarious state. Vicksburg, the last Confederate stronghold on the Mississippi River, was under siege, threatening to split the South in two. Economic woes and dwindling resources plagued the Confederate home front.

Lee envisioned a daring offensive: a thrust north into Pennsylvania. His objectives were manifold: to relieve pressure on Vicksburg, to disrupt Union supply lines, to draw the Army of the Potomac away from Washington D.C., and, most crucially, to force a decisive battle on Union soil. A major victory in the North, Lee believed, could shatter Union morale, potentially lead to European recognition of the Confederacy, and perhaps even compel Washington to sue for peace. It was a high-stakes gamble, but Lee, a general famed for his audacity, was willing to take it.

On June 3, 1863, the Army of Northern Virginia, nearly 75,000 strong, began its march. The Union, initially caught off guard, reacted by sending its own Army of the Potomac – over 90,000 men – north in pursuit. Just three days before the battle, President Lincoln, frustrated with the cautious Major General Joseph Hooker, replaced him with Major General George G. Meade, a less flamboyant but highly competent officer. Meade, a Pennsylvanian himself, suddenly found himself tasked with defending his home state and, indeed, the Union itself.

A critical misstep for Lee during the advance was the absence of his cavalry commander, Major General J.E.B. Stuart. Stuart, riding off on an ambitious raid around the Union army, deprived Lee of his "eyes and ears," leaving him largely blind to the movements and strength of Meade’s forces as they converged. This intelligence vacuum would prove costly.

Day 1: July 1, 1863 – The Unexpected Collision

The battle began almost by accident. On the morning of July 1st, Confederate forces, under Lieutenant General A.P. Hill, marched east towards the small crossroads town of Gettysburg, largely seeking shoes from a rumored supply in town. They were met by Union cavalry under Brigadier General John Buford, who immediately recognized the strategic importance of the high ground south of the town. Buford’s dismounted troopers fought tenaciously, delaying the Confederate advance and buying precious time for Union infantry to arrive.

"They will attack you in the morning and they will come with a rush," Buford had accurately predicted, setting the stage for the desperate stand. The first Union infantry to arrive was the I Corps, led by the charismatic Major General John Reynolds. Reynolds, a Pennsylvanian beloved by his troops, personally directed his men into position. Tragically, he was killed early in the fighting, becoming the highest-ranking officer on either side to die at Gettysburg. His loss was a profound blow to the Union command.

Despite initial Union resistance, the sheer weight of Confederate numbers began to tell. More Confederate forces, under Lieutenant General Richard Ewell, arrived from the north. The Union I and XI Corps, stretched thin and outflanked, were eventually overwhelmed. They collapsed and retreated in disarray through Gettysburg, seeking refuge on the hills south of town: Cemetery Hill and Culp’s Hill.

This high ground, naturally defensible, became the Union’s salvation. Major General Winfield Scott Hancock, sent by Meade to assess the situation, quickly organized the retreating troops into a defensive line. The day ended with a critical decision by Ewell. Ordered by Lee to take Cemetery Hill "if practicable," Ewell hesitated, believing the Union position too strong and his men too exhausted. This decision, or lack thereof, allowed the Union to solidify its hold on the crucial high ground, a strategic error that would haunt the Confederacy.

Day 2: July 2, 1863 – The Bloody Flanks

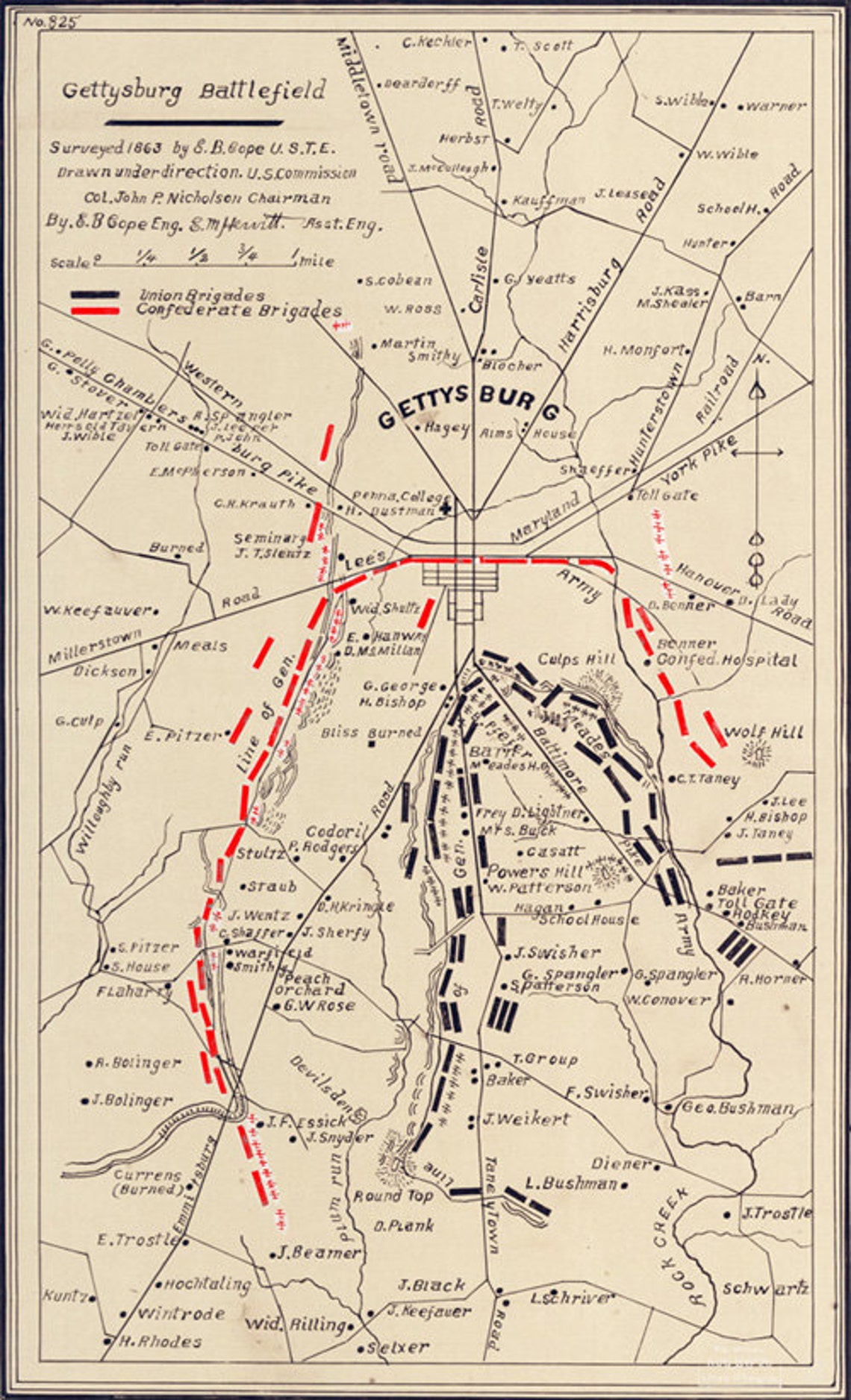

Overnight, both armies converged on Gettysburg. The Union formed a strong defensive line resembling a fishhook, with Culp’s Hill and Cemetery Hill forming the barb and bend, and Cemetery Ridge stretching south to two rocky outcroppings: Little Round Top and Big Round Top.

Lee, still confident of victory, planned a massive assault on the Union flanks. He ordered Lieutenant General James Longstreet, his trusted "Old Warhorse," to attack the Union left, while Ewell was to demonstrate against the Union right and attack if the opportunity arose.

Longstreet’s attack, however, was delayed, and when it finally came in the late afternoon, it met a Union line in a state of flux. Major General Daniel Sickles, commanding the Union III Corps, had controversially moved his troops forward from Cemetery Ridge to a more exposed position on higher ground at the Peach Orchard and Devil’s Den, creating a salient vulnerable to attack from multiple sides.

The fighting that erupted in the Peach Orchard, the Wheatfield, and Devil’s Den was among the most brutal of the war. Union and Confederate soldiers clashed in close quarters, the landscape becoming a bloody tableau of desperate charges and countercharges. Casualties mounted rapidly on both sides.

The most famous action of the day occurred at Little Round Top. This seemingly insignificant hill, if taken by the Confederates, would have allowed them to enfilade the entire Union line on Cemetery Ridge. Barely defended, it was saved by the heroic actions of Colonel Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain and his 20th Maine Regiment. Low on ammunition, Chamberlain ordered a desperate, but ultimately successful, bayonet charge down the hill, routing the attacking Confederates and securing the Union flank. It was a pivotal moment, described by many historians as saving the Union army.

Meanwhile, Ewell’s attacks on Culp’s Hill and East Cemetery Hill were largely unsuccessful, though some Confederate troops briefly gained a foothold on Culp’s Hill, setting the stage for renewed fighting the next morning.

Day 3: July 3, 1863 – The High Water Mark

Despite the heavy losses and the failure to break the Union lines on Day 2, Lee remained undeterred. Against the advice of Longstreet, who advocated for a flanking maneuver, Lee decided on a frontal assault against the center of the Union line on Cemetery Ridge. He believed the Union flanks were now too strong and that a concentrated blow at the center, after a massive artillery barrage, would shatter Meade’s forces.

The morning began with renewed, ferocious fighting on Culp’s Hill, as Union forces successfully drove back the Confederates who had gained ground the previous evening. Then, around 1 p.m., the "Great Cannonade" began. For nearly two hours, over 150 Confederate cannons pounded the Union positions on Cemetery Ridge. The earth trembled, the air filled with the roar of artillery and the screams of shells. Union artillery responded, creating a deafening symphony of destruction. Yet, despite the terrifying spectacle, much of the Confederate fire overshot its mark, doing less damage than intended.

At approximately 3 p.m., after the bombardment ceased (partially due to Union artillery intentionally slowing its fire to make the Confederates believe their guns had been silenced), the order was given. Brigadier General George Pickett, along with divisions from Hill’s and Longstreet’s corps, formed into a massive line, nearly 12,500 strong, and began their fateful march across the open fields towards Cemetery Ridge, a distance of nearly a mile.

This became known as "Pickett’s Charge." It was an awe-inspiring, yet utterly doomed, display of courage and sacrifice. As the Confederates advanced, they were met by a murderous hail of Union artillery, then rifle fire. The lines withered, men fell by the hundreds, but they pressed on. A few Confederates managed to breach the Union line at a place known as "The Angle," momentarily reaching the stone wall. This was the "High Water Mark of the Confederacy" – the furthest north the Confederate army would ever penetrate, and the closest it would come to victory.

But the Union defenders, reinforced and fighting desperately, held firm. The Confederates, lacking support and decimated, were forced to retreat, leaving behind thousands of dead, wounded, and captured. The charge had been a catastrophic failure.

As the shattered remnants of his division returned, a devastated General Pickett famously told Lee, "General, I have no division." Lee, taking full responsibility, replied, "It’s all my fault. It is I who have lost this fight, and you must help me out of it the best way you can."

While Pickett’s Charge unfolded, a significant cavalry battle took place three miles to the east, on East Cavalry Field. J.E.B. Stuart, finally back with Lee, attempted to flank the Union right and exploit the anticipated breakthrough on Cemetery Ridge. He was met and decisively repulsed by Union cavalry, including a brigade led by the young and audacious Brigadier General George Armstrong Custer.

The Aftermath and Legacy

The Battle of Gettysburg concluded with a decisive Union victory. The Confederate army, shattered and exhausted, began its long, somber retreat back to Virginia on July 4th. Meade, cautious and battered himself, did not pursue with the vigor Lincoln desired, allowing Lee’s army to escape across the Potomac. Despite Lincoln’s disappointment, the strategic victory was immense.

The cost was staggering. In three days, approximately 51,000 soldiers became casualties – killed, wounded, or missing – making Gettysburg the bloodiest battle in American history. The Union suffered around 23,000 casualties, while the Confederacy endured approximately 28,000, representing over a third of Lee’s army.

Gettysburg, coupled with the fall of Vicksburg to Union forces on July 4th, marked the true turning point of the Civil War. The Confederacy would never again launch a major offensive into Union territory. From this point forward, the South was largely on the defensive, its resources dwindling, its manpower exhausted. The dream of independence, while not yet extinguished, had been dealt a mortal blow.

Four months later, on November 19, 1863, a portion of the battlefield was dedicated as a national cemetery. There, President Abraham Lincoln delivered his immortal Gettysburg Address, a mere 272 words that redefined the purpose of the war and the meaning of American democracy. He spoke not of victory, but of sacrifice, of a "new birth of freedom," and of the enduring principle that "government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth."

Gettysburg remains a powerful symbol of national struggle and resilience. It was a crucible where the fate of the nation hung in the balance, a testament to the courage and suffering of ordinary men, and a stark reminder of the immense human cost of war. More than just a battle, Gettysburg was a pivotal moment that ensured the Union would endure, setting America on an irreversible path towards becoming the united nation it is today. Its echoes resonate still, a silent testament to the "high water mark" that forever changed the course of American history.