The Hooded Menace: A Century and a Half of the Ku Klux Klan’s Enduring Shadow

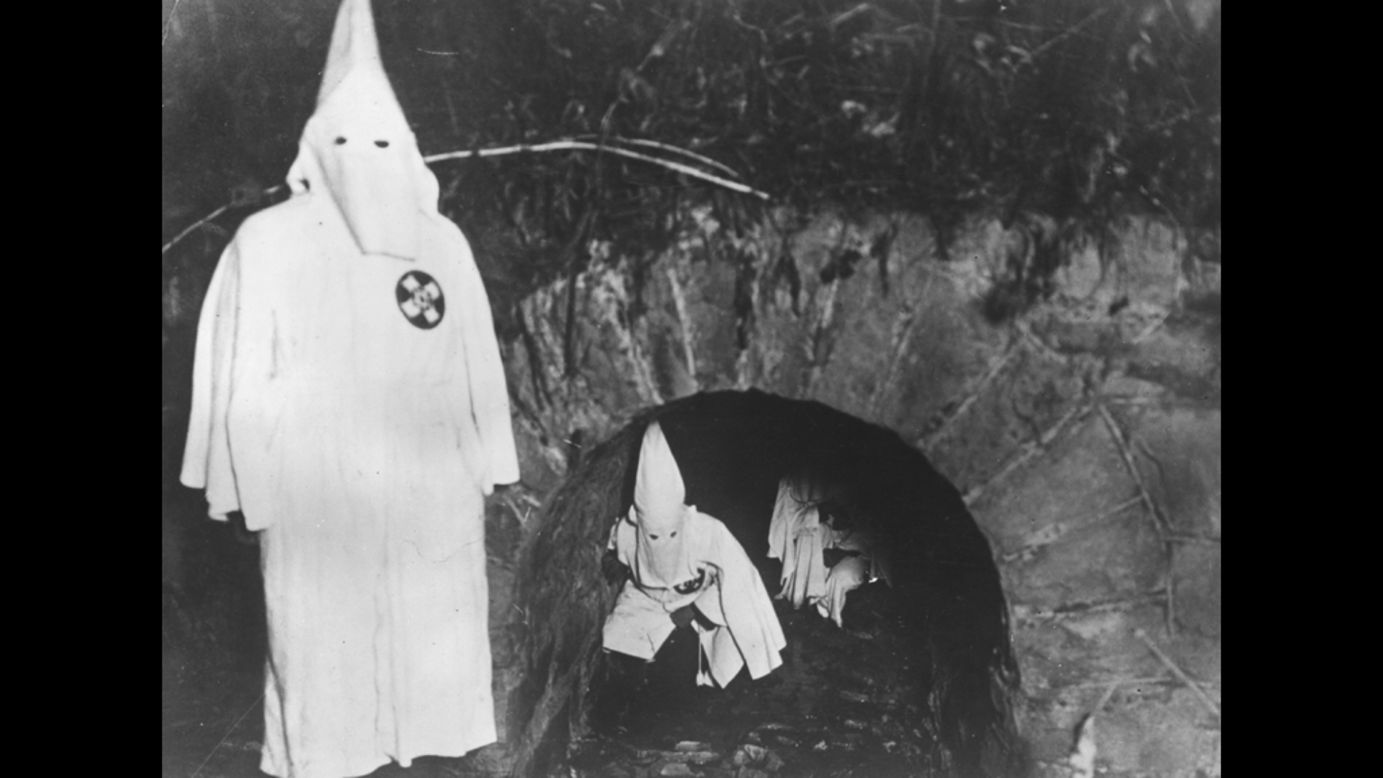

Few symbols in American history evoke as much visceral revulsion and chilling dread as the image of the white-hooded figures of the Ku Klux Klan. For over 150 years, this notorious organization has haunted the nation’s conscience, a stark embodiment of racial hatred, nativism, and violent extremism. From its origins in the ashes of the Confederacy to its fragmented, though still virulent, modern iterations, the KKK has consistently sought to undermine the ideals of equality and justice, leaving a blood-stained legacy that continues to resonate in the fabric of American society.

The story of the Ku Klux Klan is not a singular, monolithic narrative, but rather a series of distinct, yet ideologically linked, movements that rose and fell in response to specific historical contexts. Each iteration shared core tenets of white supremacy and an unwavering commitment to maintaining a racial hierarchy, often through terror and intimidation.

The First Klan: An Invisible Empire Born of Reconstruction

The first incarnation of the Ku Klux Klan emerged in Pulaski, Tennessee, in December 1865, just months after the end of the Civil War. Initially, it was conceived by six former Confederate officers as a social club, a secret fraternity for bored young men in a defeated South. The name itself, "Ku Klux," is thought to derive from the Greek word "kuklos," meaning circle, while "Klan" was added for alliteration.

However, its playful origins quickly devolved into something far more sinister. As Reconstruction policies took hold – granting voting rights to Black men and allowing them to hold political office – the Klan rapidly transformed into a white supremacist terrorist organization. Its primary aim was to restore white control, suppress the political and economic advancement of newly freed slaves, and intimidate "carpetbaggers" (Northerners who moved South) and "scalawags" (white Southerners who cooperated with Reconstruction efforts).

Members, often disguised in white robes and hoods to appear as ghosts of Confederate soldiers, engaged in a campaign of intimidation, flogging, arson, rape, and murder. They targeted Black voters, Republican officeholders, and anyone who supported racial equality. The psychological warfare was as potent as the physical violence; the specter of the Klan loomed over Southern communities, enforcing a brutal social order.

Nathan Bedford Forrest, a revered Confederate cavalry general, became the first Grand Wizard of the Invisible Empire, though his actual level of control over the disparate local chapters is debated. By the early 1870s, facing federal intervention through the Enforcement Acts (also known as the Ku Klux Klan Acts), which allowed President Ulysses S. Grant to suspend habeas corpus and use federal troops to suppress the Klan, the first iteration largely faded, its reign of terror curtailed, but its ideology deeply embedded.

The Second Klan: A National Phenomenon of Nativism and "100% Americanism"

The Klan experienced a dramatic resurgence in the early 20th century, a rebirth fueled by a potent cocktail of anxieties: rapid industrialization, increasing immigration from Southern and Eastern Europe, the Great Migration of Black Americans to Northern cities, and a deep-seated fear of social change. This Second Klan was formally re-established on Stone Mountain, Georgia, on Thanksgiving night, 1915, by William J. Simmons, a former Methodist preacher and fraternal organization promoter.

Crucially, this revival was heavily influenced by D.W. Griffith’s controversial film, "The Birth of a Nation," released in 1915. The film, a racist epic that glorified the first Klan as saviors of the white South and depicted Black men as sexual predators and dangerous figures, played a monumental role in popularizing the Klan’s imagery and ideology nationwide. President Woodrow Wilson even screened the film at the White House, famously remarking, "It is like writing history with lightning, and my only regret is that it is all so terribly true."

Unlike its predecessor, the Second Klan cast a far wider net of hatred. While maintaining its anti-Black stance, it expanded its targets to include Catholics, Jews, immigrants, and those deemed "un-American." It championed a form of aggressive "100% Americanism," advocating for strict moral codes (often Prohibition), Protestant supremacy, and a return to what it perceived as traditional values.

This era marked the Klan’s peak in terms of membership and political influence. By the mid-1920s, its estimated membership ranged from 3 to 6 million people, extending far beyond the South into states like Indiana, Oregon, and Colorado. Its members included politicians, police officers, and respected community leaders. They held massive public rallies, paraded in their distinctive robes, and openly engaged in political organizing. In some states, Klan members controlled legislatures and governorships.

However, the Second Klan’s decline was as swift as its rise. A series of scandals, internal power struggles, and increasing public disillusionment led to its rapid loss of influence by the late 1920s. The most damaging was the 1925 conviction of D.C. Stephenson, the Grand Dragon of the Indiana Klan, for the rape and murder of a young woman, which exposed the hypocrisy and criminality at the organization’s highest levels. The Great Depression further eroded its base, as economic concerns overshadowed nativist fears.

The Third Klan: Resurgence in the Civil Rights Era

After a period of dormancy during World War II, the Klan once again surged into prominence in the 1950s and 1960s, driven by its fierce opposition to the burgeoning Civil Rights Movement. This Third Klan was not a unified national organization but rather a collection of independent, often rival, chapters and factions. Their shared goal, however, was to resist racial integration and maintain segregation through any means necessary, including extreme violence.

This era saw some of the most heinous acts of terror attributed to the Klan. They bombed homes, churches, and synagogues, murdered activists, and assaulted peaceful protestors. Notable atrocities include:

- The 1963 bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, which killed four young African American girls.

- The 1964 murder of civil rights workers James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner in Mississippi, immortalized as the "Mississippi Burning" case.

- The 1965 murder of Viola Liuzzo, a white civil rights activist from Michigan, after the Selma to Montgomery march.

The federal government, particularly the FBI under J. Edgar Hoover, increasingly targeted the Klan, using informants and counterintelligence programs (COINTELPRO) to disrupt its activities. Public outrage over the Klan’s brutality, coupled with effective legal action and the eventual passage of landmark civil rights legislation, gradually weakened its power. Many Klan members were eventually prosecuted for their crimes, often decades later, bringing some measure of justice to their victims’ families.

The Modern Klan: Fragmented and Fading, Yet Still Present

Today, the Ku Klux Klan exists as a shadow of its former self. It is no longer a singular, powerful organization but a collection of disparate, often tiny, and mutually hostile groups, typically numbering in the low thousands nationwide. These groups frequently operate under various names, such as the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, the Loyal White Knights, or the United Klans of America.

While their numbers have dwindled significantly, their core ideology remains unchanged: white supremacy, anti-Semitism, homophobia, and xenophobia. They often align with broader white supremacist and neo-Nazi movements, finding common ground in shared hatreds. The internet has provided a new platform for recruitment and propaganda, allowing these groups to connect with sympathizers across geographical boundaries and spread their messages of hate with relative ease.

Despite their diminished size and influence, modern Klan groups still occasionally hold rallies, engage in cross burnings (often on private property), and attempt to recruit new members. Their presence serves as a stark reminder that the ideology of racial hatred, though pushed to the fringes of mainstream society, has not been eradicated.

An Enduring Symbol of Hate

The Ku Klux Klan’s enduring legacy is a dark stain on the American narrative. It represents the persistent struggle against racial prejudice and the fragility of democratic ideals when confronted by organized hatred. Each time the Klan has resurfaced, it has exploited societal anxieties and divisions, demonstrating how easily fear and ignorance can be weaponized.

While the days of millions of robed Klansmen openly parading in city streets are thankfully long past, the lessons of the KKK’s history remain profoundly relevant. It serves as a powerful cautionary tale about the dangers of unchecked extremism, the corrosive nature of racial hatred, and the constant vigilance required to uphold the principles of equality, justice, and human dignity for all. The hooded menace may be diminished, but the shadow it casts serves as a perpetual reminder of America’s ongoing journey toward a more perfect union.