The Indelible Stain: Slavery, Division, and the Crucible of the American Civil War

Few chapters in American history are as searing, as morally complex, and as profoundly transformative as the intertwining narratives of slavery and the Civil War. It is a story of a nation born of high ideals, yet stained by a brutal "peculiar institution" that would ultimately tear it asunder, demanding a cataclysmic conflict to forge a more perfect, albeit still imperfect, union. From the arrival of the first enslaved Africans to the thunder of cannon fire, this saga charts the trajectory of a republic wrestling with its original sin, culminating in a violent reckoning that redefined freedom itself.

The year 1619 marks a grim genesis, as a Dutch ship arrived at Point Comfort, Virginia, carrying "20 and odd" enslaved Africans. This was not merely the beginning of forced labor in the nascent colonies, but the planting of a seed that would grow into a deeply rooted economic and social system. Initially, the legal status of these individuals was fluid, often akin to indentured servitude. However, over time, the demand for cheap labor in the burgeoning tobacco, and later cotton, sugar, and rice plantations of the South, solidified their fate. By the late 17th century, chattel slavery—a system where enslaved people were considered property, not persons, and their bondage was hereditary—became firmly entrenched in law and custom.

This peculiar institution was the bedrock of the Southern economy. Vast plantations, stretching across the fertile lands from the Carolinas to Louisiana, generated immense wealth for their white owners, but at an unimaginable human cost. Millions of Africans and their descendants were stripped of their dignity, their families, their culture, and their very humanity. They were bought, sold, beaten, raped, and worked from sunup to sundown under the constant threat of violence. "I was a slave – a slave for life," recounted Frederick Douglass, himself a former slave and towering abolitionist figure. "I was bought and sold, and passed from hand to hand. I was a thing."

Yet, even in the face of such profound oppression, resistance simmered. Covert acts of sabotage, feigned illness, and the preservation of African cultural traditions were commonplace. Overt revolts, though rare and brutally suppressed, like Nat Turner’s rebellion in 1831, sent shivers through the white South, leading to even harsher slave codes. The Underground Railroad, a clandestine network of safe houses and routes, offered a perilous path to freedom, guided by brave individuals like Harriet Tubman, who famously declared, "I never ran my train off the track and I never lost a passenger."

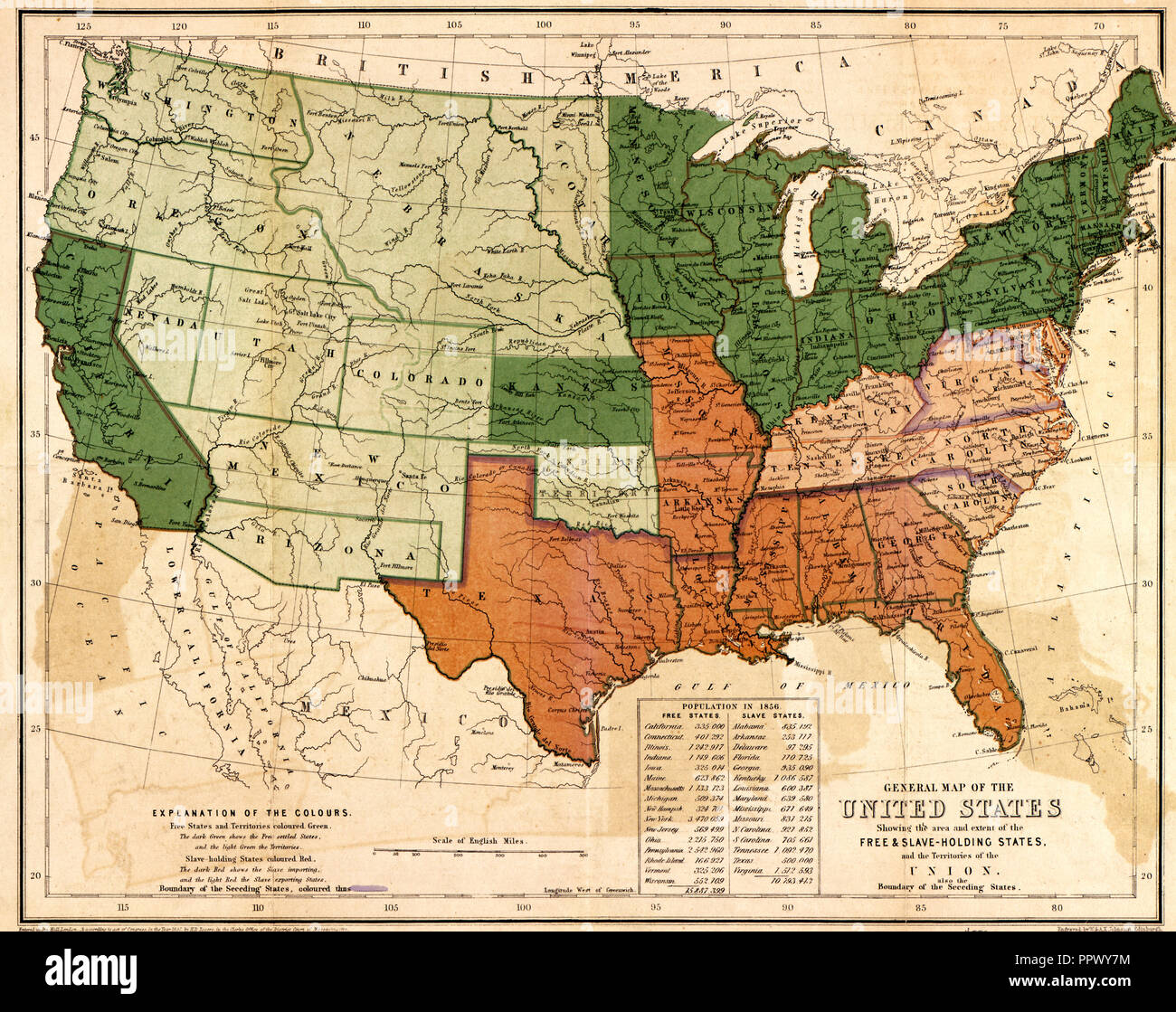

As the nation expanded westward, the question of slavery’s extension became the defining political battle. The delicate balance of power between free and slave states in Congress fueled a series of increasingly volatile compromises. The Missouri Compromise of 1820 attempted to draw a line, admitting Missouri as a slave state and Maine as a free state, while prohibiting slavery north of the 36°30′ parallel in the Louisiana Purchase territory. But this was merely a temporary balm.

Decades later, the Compromise of 1850, while admitting California as a free state, included a draconian Fugitive Slave Act, which mandated that all citizens assist in the capture of runaway slaves, denying them legal rights and turning many Northerners into unwilling participants in the institution. This act, perhaps more than any other, galvanized Northern opposition, transforming the abstract concept of slavery into a tangible infringement on individual liberties. Harriet Beecher Stowe’s monumental novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852), depicting the brutal realities of slavery, sold hundreds of thousands of copies, stirring moral outrage across the North and solidifying abolitionist sentiment.

The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, championed by Senator Stephen Douglas, ignited a fuse. It proposed that settlers in new territories decide on the legality of slavery through "popular sovereignty," effectively repealing the Missouri Compromise. The result was "Bleeding Kansas," a miniature civil war where pro-slavery and anti-slavery factions clashed violently, leaving scores dead and demonstrating the impossibility of a peaceful resolution.

The Supreme Court delivered its own devastating blow in the 1857 Dred Scott v. Sandford decision, ruling that African Americans, whether enslaved or free, could not be American citizens and therefore had no standing to sue in federal court. Furthermore, the Court declared the Missouri Compromise unconstitutional, asserting that Congress had no power to prohibit slavery in the territories. Chief Justice Roger B. Taney infamously declared that Black people "had no rights which the white man was bound to respect." This ruling shocked the North, undermining the very idea of a legal path to freedom and fueling the conviction that a "slave power conspiracy" was at work.

The stage was set for an "irrepressible conflict," a term coined by Senator William H. Seward. The newly formed Republican Party, largely a Northern, anti-slavery expansion party, gained momentum. When Abraham Lincoln, a relatively unknown lawyer from Illinois, won the presidency in November 1860 on an anti-slavery platform (though initially not an abolitionist), the South saw the writing on the wall. Within weeks, South Carolina seceded from the Union, followed swiftly by ten other Southern states, forming the Confederate States of America. Their secession documents explicitly cited the protection of slavery as their primary motivation.

The first shots of the Civil War rang out on April 12, 1861, as Confederate batteries fired on Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina. What many expected to be a short, glorious conflict quickly devolved into a protracted, brutal war. The Union’s initial aim was to preserve the nation, not to abolish slavery. Lincoln famously stated, "My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or to destroy slavery." However, as the war dragged on, the strategic and moral imperatives began to shift. Enslaved people fleeing to Union lines, declared "contraband of war," highlighted the institution’s vulnerability.

The turning point came in 1862. After the Union victory at Antietam, the bloodiest single day in American military history, Lincoln seized the moment. On January 1, 1863, he issued the Emancipation Proclamation, declaring all enslaved people in Confederate-held territory to be free. This act fundamentally transformed the nature of the war. It was no longer solely about preserving the Union; it became a war for human freedom. It also opened the door for African Americans to serve in the Union army, with over 180,000 Black soldiers joining the United States Colored Troops (USCT), fighting valiantly for their own liberation.

The subsequent years saw monumental battles that shaped the course of the war. Gettysburg (July 1863) marked the "high-water mark" of the Confederacy, as General Robert E. Lee’s invasion of the North was decisively repulsed. Simultaneously, Vicksburg fell to Union forces under Ulysses S. Grant, securing control of the Mississippi River and splitting the Confederacy. Grant’s relentless "total war" strategy, combined with General William Tecumseh Sherman’s devastating "March to the Sea," systematically dismantled the Confederacy’s ability and will to fight.

On April 9, 1865, Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox Court House, effectively ending the war. The cost was staggering: an estimated 620,000 to 750,000 soldiers died, more than in all other American wars combined until the Vietnam War. The South was devastated, its economy in ruins. Just five days after Appomattox, President Lincoln was assassinated, depriving the nation of its guiding hand in the arduous task of reunification.

The Civil War ultimately achieved its dual objectives: the preservation of the Union and the abolition of slavery. The 13th Amendment, ratified in December 1865, formally outlawed slavery throughout the United States. It was followed by the 14th Amendment (granting citizenship and equal protection) and the 15th Amendment (granting Black men the right to vote) during the Reconstruction era, attempts to build a truly multiracial democracy.

However, the legacy of slavery and the war cast a long shadow. The promise of Reconstruction was largely betrayed by the rise of white supremacy, Jim Crow laws, and systemic racial discrimination that persisted for another century. The scars of division, though healed by time and struggle, remain part of the national consciousness.

The American Civil War stands as a testament to the profound consequences of moral compromise and the ultimate triumph of fundamental human rights, bought at an almost unfathomable price. It was a crucible that forged a new nation, one irrevocably changed by the experience, forever grappling with the ideals it espouses and the historical realities it has faced. The story of slavery and the Civil War is not merely a chapter in the past; it is an enduring lesson in the ongoing journey towards justice and equality, a constant reminder of the vigilance required to uphold the principles of liberty for all.