The Invisible Scourge: Revisiting the 1918 Spanish Flu Pandemic

As the Great War neared its brutal climax in 1918, claiming millions of lives in the trenches of Europe, another, far deadlier enemy emerged from the shadows. Silent, indiscriminate, and invisible, it swept across the globe with a ferocity that dwarfed the battlefield’s carnage. This was the H1N1 influenza virus, colloquially known as the Spanish Flu, a pandemic that would infect an estimated one-third of the world’s population and kill at least 50 million people, with some estimates reaching as high as 100 million. It was a global cataclysm that reshaped societies, overwhelmed healthcare systems, and left an indelible mark on human history, yet remains, for many, a forgotten tragedy.

The moniker "Spanish Flu" is, ironically, a misnomer. Spain, a neutral country during World War I, had no wartime censorship of its press. When the illness struck its population, including King Alfonso XIII, Spanish newspapers reported on it openly and extensively. In contrast, Allied and Central Powers alike suppressed news of the burgeoning epidemic to maintain morale and avoid giving the impression of weakness. Thus, while the disease was raging worldwide, it was only in Spain that the public received honest reporting, leading to the false impression that the pandemic originated there.

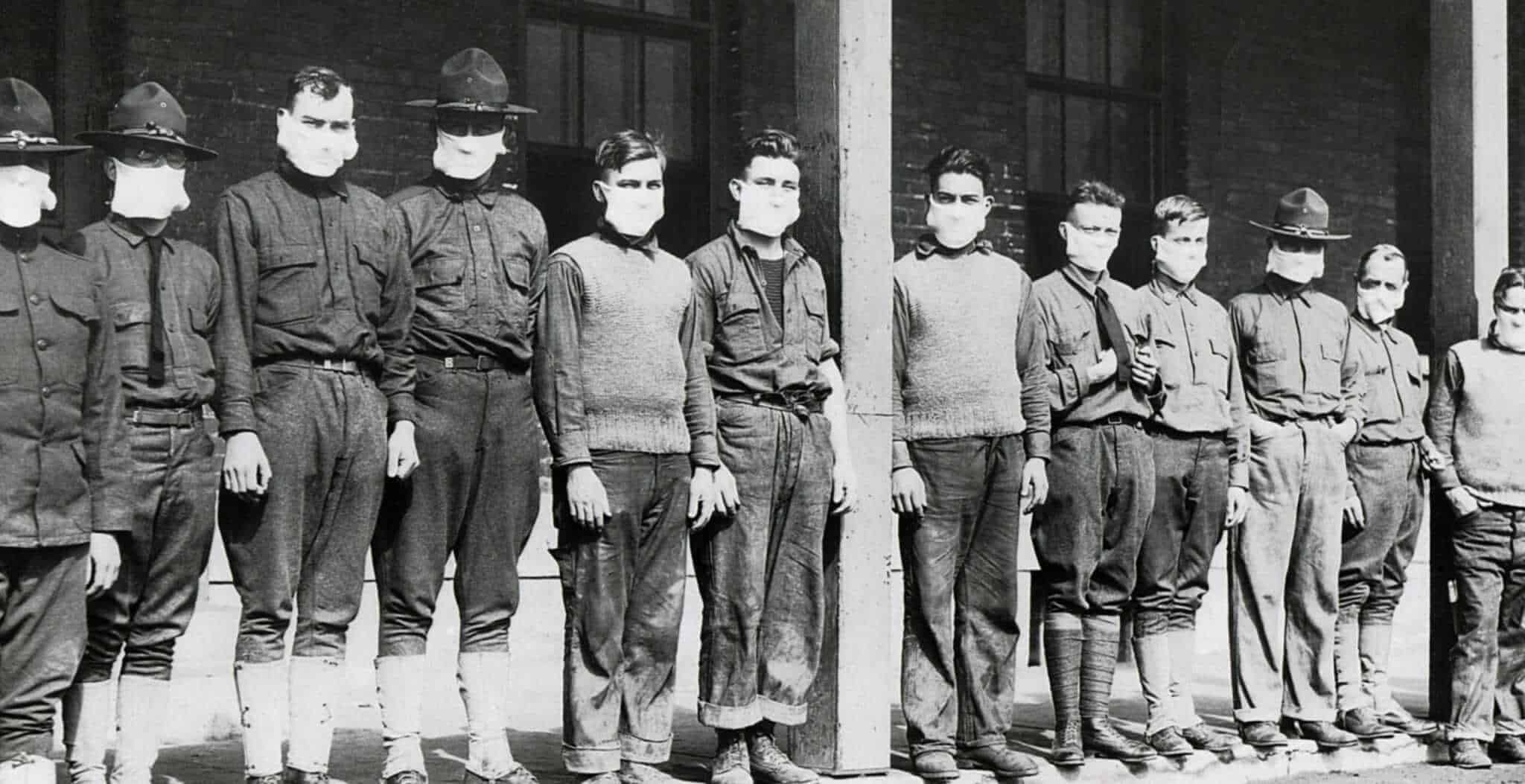

The true origin of the 1918 flu remains a subject of historical debate, but leading theories point to various locations, including a military camp in Kansas, USA; a British army base in France; or even East Asia. What is undeniable is that the confluence of World War I created a perfect storm for its rapid, global dissemination. Millions of soldiers, packed into crowded barracks and troop transports, became ideal incubators and vectors for the virus. As these troops moved across continents, they carried the unseen killer with them, sowing the seeds of contagion in every port and camp.

The first wave of the flu, in the spring of 1918, was relatively mild, often mistaken for a common cold. While disruptive, it caused little alarm. The calm, however, was merely the prelude to an unprecedented storm. The virus mutated, and by late summer and early autumn, a second, far more virulent wave erupted. This strain was particularly lethal, distinguishing itself from typical influenza by its "W-shaped" mortality curve. While most flu strains disproportionately affect the very young and the very old, the 1918 pandemic devastated young, healthy adults aged 20 to 40 – the prime demographic for military service and the backbone of society.

The symptoms were horrific and progressed with terrifying speed. Victims would initially experience fever, headache, and muscle pain. Within hours or days, however, their condition would deteriorate dramatically. A characteristic sign was "heliotrope cyanosis," where the skin, particularly the face and extremities, would turn a dusky blue or purple due as their lungs filled with fluid, leading to severe oxygen deprivation. Many patients would drown in their own bodily fluids, sometimes within 24 to 48 hours of their first symptoms. Dr. Victor Vaughan, a prominent American physician, famously described the scene at Camp Devens, Massachusetts, in September 1918: "The patients with the most profound toxemia… develop a cyanosis of the most marked type… It is only a matter of a few hours then until death comes, and it is a horrible death from suffocation."

The medical community of 1918 was largely powerless against such a foe. The concept of viruses was still in its infancy, and there were no antivirals, no antibiotics to combat the secondary bacterial pneumonia that often proved fatal, and no vaccine. Doctors and nurses, many of whom were already stretched thin by the war effort, worked tirelessly but often fruitlessly. Their tools were limited to palliative care: aspirin for fever and pain, camphor, quinine, and even bloodletting – remedies often ineffective and sometimes harmful, especially with the high dosages of aspirin sometimes prescribed, which could exacerbate lung damage.

Public health responses varied widely but shared common themes of desperation and inadequacy. Cities implemented quarantines, closed schools, theaters, churches, and other public gathering places. San Francisco famously passed an ordinance requiring citizens to wear gauze masks in public, enforced by "flu fighters" who would fine or arrest those who refused. Posters and newspaper advertisements urged hand washing, avoiding crowds, and covering coughs and sneezes – measures that sound remarkably familiar today. Yet, the sheer scale of the outbreak, coupled with limited scientific understanding and the ongoing war, meant these efforts were often overwhelmed.

The societal impact was profound. Daily life ground to a halt. Businesses closed, public transportation was disrupted, and essential services faltered as workers succumbed to the illness. Funeral homes were overwhelmed, and undertakers and gravediggers struggled to keep up with the grim procession of the dead. In many places, bodies piled up, sometimes buried in mass graves, a stark testament to the pandemic’s merciless efficiency. The psychological toll was immense; fear and grief permeated communities, leaving a generation scarred by loss.

As abruptly as it appeared, the lethal second wave began to recede by the winter of 1918-1919. A third, milder wave occurred in the spring of 1919, but by then, the virus had largely run its course, or perhaps mutated into a less virulent form, or a sufficient portion of the population had developed immunity. The 1918 H1N1 virus did not vanish; it continued to circulate seasonally for decades, eventually evolving into the common flu strains we still encounter.

The Spanish Flu, despite its devastating global reach, faded from public memory with surprising speed. Overshadowed by the end of World War I and the subsequent economic booms and busts, its narrative was largely suppressed or forgotten, perhaps because there was no clear enemy to defeat, no grand victory to celebrate, only collective trauma. Survivors rarely spoke of it, and academic interest waned for decades.

However, the ghost of 1918 has never truly disappeared. Its lessons, though slow to be acknowledged, are crucial. The pandemic underscored the terrifying potential of a novel respiratory virus to cripple societies and economies. It highlighted the critical importance of public health infrastructure, rapid scientific response, and transparent communication. The development of modern virology, vaccine technology, and global health surveillance systems owes much to the chilling precedent set by the 1918 pandemic.

In recent years, with the emergence of new viral threats like SARS, MERS, and most profoundly, COVID-19, the 1918 pandemic has returned to the forefront of our collective consciousness. Historians, epidemiologists, and public health officials have meticulously studied its trajectory, seeking insights that could inform contemporary responses. The echoes of "flattening the curve," mask mandates, social distancing, and the race for vaccines resonate directly from the experiences of a century ago.

The 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic stands as a stark, humbling reminder of humanity’s vulnerability to the microbial world. It teaches us that even in an era of advanced science and technology, a silent, invisible enemy can bring the world to its knees. Its legacy is not just one of death and despair, but also a testament to human resilience, the imperative of scientific inquiry, and the enduring need for global cooperation in the face of shared threats. The invisible scourge of 1918 may have passed, but its silent warning continues to reverberate, urging us to remain vigilant, prepared, and united against the pandemics yet to come.