The Iron Cage of Jim Crow: America’s Century of Legalized Apartheid

A century ago, in the American South, a shadow fell across the land, a pervasive system of racial oppression so deeply woven into the fabric of society that it touched every aspect of life for African Americans. It was known as Jim Crow, a cruel and elaborate edifice of laws, customs, and violence designed to enforce white supremacy and relegate Black citizens to a permanent state of subjugation. From the late 19th century through the mid-20th century, Jim Crow wasn’t merely a set of discriminatory practices; it was a societal iron cage, meticulously constructed to deny freedom, dignity, and equality to millions based solely on the color of their skin.

To understand Jim Crow, one must first grasp the tumultuous period that preceded it. The Civil War had abolished slavery, and the Reconstruction era (1865-1877) saw a brief but potent push for Black civil rights, including the right to vote, hold office, and participate in public life. However, this progress was met with fierce and violent white backlash. As federal troops withdrew from the South in 1877, conservative white Democrats, often referred to as "Redeemers," regained political control. They immediately set about dismantling Reconstruction’s gains, ushering in an era of systematic disenfranchisement and segregation. The infamous "Black Codes" of the immediate post-Civil War period were precursors, attempting to bind Black laborers to plantations and restrict their freedoms, but Jim Crow would take this oppression to an unprecedented level of legal and social entrenchment.

The Legal Fiction of "Separate but Equal"

The legal cornerstone of Jim Crow was laid in 1896 with the Supreme Court’s landmark decision in Plessy v. Ferguson. Homer Plessy, a man of mixed racial heritage, deliberately sat in a "whites-only" train car in Louisiana to challenge the state’s segregation laws. The Court, in a 7-1 decision, upheld the constitutionality of "separate but equal" facilities for Black and white citizens. Justice Henry Billings Brown, writing for the majority, declared that segregation did not imply inferiority and that "legislation is powerless to eradicate racial instincts."

The lone dissenter, Justice John Marshall Harlan, penned a prescient and scathing rebuke that would echo through history. He famously argued: "Our Constitution is color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens. In respect of civil rights, all citizens are equal before the law… The arbitrary separation of citizens, on the basis of race, while they are on a public highway, is a badge of servitude wholly inconsistent with the civil freedom and the equality before the law established by the Constitution." Harlan’s words, ignored for decades, perfectly captured the hypocrisy of "separate but equal," which in practice always meant "separate and unequal."

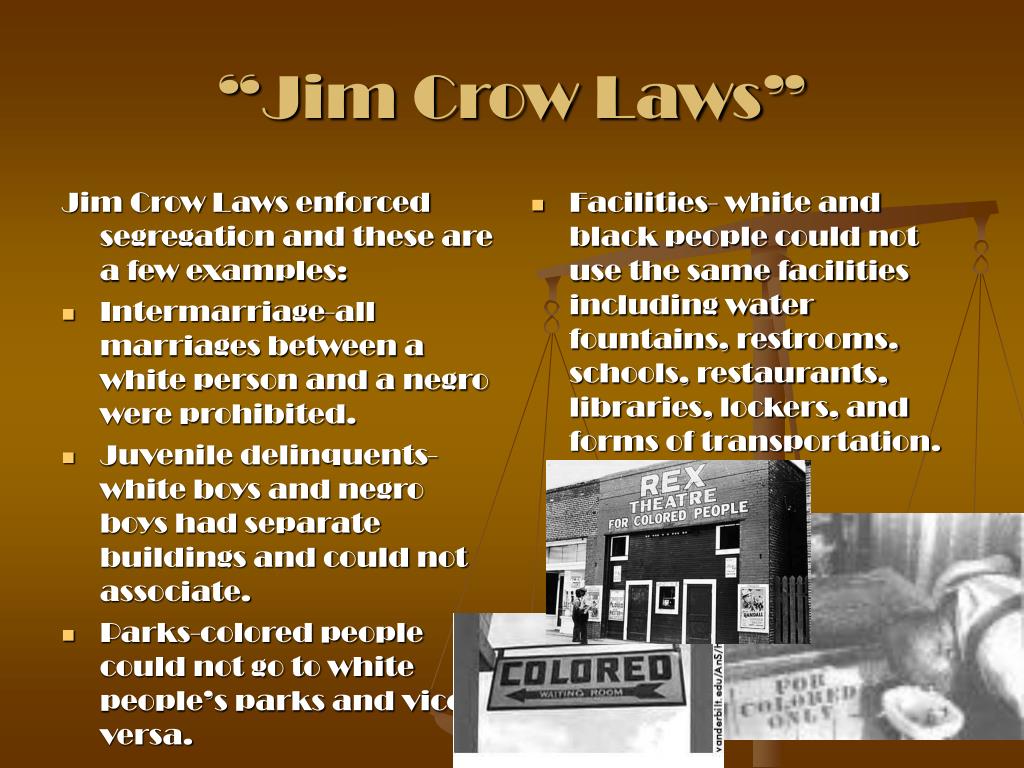

With Plessy v. Ferguson providing judicial sanction, Southern states rapidly enacted a labyrinthine web of Jim Crow laws that dictated nearly every interaction between races. These laws mandated segregation in schools, hospitals, transportation, public restrooms, water fountains, restaurants, hotels, and even cemeteries. There were separate waiting rooms in bus and train stations, separate entrances to buildings, and even separate Bibles for swearing in witnesses in court. The absurdity of some laws highlighted the depth of racial animosity: Oklahoma, for example, required separate telephone booths.

Disenfranchisement: Silencing the Black Vote

Beyond segregation, a primary goal of Jim Crow was the political subjugation of African Americans. Following Reconstruction, Black men had exercised their right to vote, often serving in state legislatures and even Congress. Jim Crow architects systematically stripped away this hard-won right through a combination of legal obstacles and intimidation.

- Poll Taxes: Voters were required to pay a fee to cast a ballot, a significant barrier for impoverished Black farmers and laborers.

- Literacy Tests: These tests, often administered with subjective bias, required prospective voters to interpret complex passages of text or answer obscure questions about civics. White registrars frequently passed illiterate white voters while failing highly educated Black ones.

- Grandfather Clauses: To ensure white illiterates could still vote, many states enacted "grandfather clauses" that exempted individuals from poll taxes and literacy tests if their ancestors had been eligible to vote before 1866 or 1867. This effectively excluded all Black Americans, whose ancestors were enslaved and thus disenfranchised.

- White Primaries: In the solidly Democratic South, the real election was often the Democratic primary. Southern states declared political parties private organizations, allowing them to restrict primary participation to white voters only, effectively shutting Black citizens out of the political process.

The impact was devastating. In Mississippi, for instance, the percentage of Black men registered to vote plummeted from over 90% in 1870 to less than 6% in 1890. This political voicelessness ensured that laws unfavorable to Black interests would continue to be passed and enforced with impunity.

Social Control and Terror: The Enforcement Arm of Jim Crow

Jim Crow was not merely a legal framework; it was a deeply ingrained social system enforced by custom, economic coercion, and brutal violence. The Ku Klux Klan and other white supremacist groups acted as extra-legal enforcers, terrorizing Black communities with lynchings, bombings, and assaults. Lynching, the public murder of an individual by a mob, often by hanging, was a particularly horrific tool of racial terror. Between 1877 and 1950, nearly 3,500 African Americans were lynched in the United States, often for perceived transgressions against the Jim Crow social order, or sometimes for no reason at all. These acts were rarely prosecuted and often occurred with the tacit approval or direct participation of local authorities.

Beyond overt violence, an intricate code of racial "etiquette" governed daily interactions. Black individuals were expected to defer to whites, avoid eye contact, and use titles like "Mr." and "Mrs." for whites, while whites often addressed Black adults by their first names or derogatory terms. Any perceived violation of these unwritten rules could lead to severe consequences, from public humiliation to violence.

Economically, Jim Crow entrenched a system of exploitation. Sharecropping, a system where Black farmers worked land owned by whites in exchange for a share of the crop, often trapped them in perpetual debt. Limited access to education, skilled trades, and capital ensured that most Black Americans remained at the bottom of the economic ladder, with little opportunity for upward mobility.

The Human Cost: A Life in the "Colored" World

For African Americans living under Jim Crow, life was a constant navigation of indignity, danger, and systemic disadvantage. Imagine a young child in Mississippi unable to attend the well-funded, modern white school, instead relegated to a dilapidated, under-resourced "colored" school with outdated textbooks. Imagine a weary traveler, unable to find a hotel or even a gas station willing to serve them, relying on the "Green Book," a guide to Black-friendly establishments, to safely traverse the country. Imagine a family, unable to bury their loved one in a dignified cemetery because of their race.

These were not isolated incidents but the daily reality for generations. The psychological toll was immense: the constant threat of violence, the gnawing awareness of one’s second-class status, the profound injustice of a system designed to crush the spirit. As the great poet Langston Hughes wrote, "What happens to a dream deferred? Does it dry up like a raisin in the sun?" For many, dreams under Jim Crow were not merely deferred but actively denied.

Resistance and the Dawning of Change

Despite the oppressive weight of Jim Crow, African Americans never ceased to resist. Early organizations like the NAACP (founded 1909) tirelessly fought legal battles against segregation and disenfranchisement. Journalists like Ida B. Wells courageously documented and exposed the horrors of lynching. Everyday people resisted in countless small ways, from refusing to give up a seat on a bus to organizing clandestine educational efforts.

The seeds of change began to sprout in the mid-20th century. World War II exposed the hypocrisy of fighting fascism abroad while maintaining racial segregation at home, prompting President Truman to desegregate the military in 1948. The Great Migration saw millions of African Americans move from the rural South to Northern and Western cities, seeking economic opportunity and an escape from Jim Crow, fundamentally altering the nation’s demographics and political landscape.

The true turning point, however, came with the burgeoning Civil Rights Movement. In 1954, the Supreme Court, in Brown v. Board of Education, finally overturned Plessy v. Ferguson, declaring "separate educational facilities are inherently unequal." This landmark decision sparked fierce resistance in the South but ignited the movement’s momentum. The Montgomery Bus Boycott (1955-1956), sparked by Rosa Parks’ courageous refusal to give up her seat, demonstrated the power of nonviolent direct action. Sit-ins, freedom rides, and mass marches, often met with brutal violence, captured national and international attention.

The eloquence and moral authority of leaders like Martin Luther King Jr., whose "I Have a Dream" speech at the 1963 March on Washington became an iconic call for racial justice, galvanized public opinion. Finally, in the mid-1960s, a series of landmark federal laws dismantled Jim Crow’s legal framework:

- The Civil Rights Act of 1964: Outlawed discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin, effectively ending legal segregation in public places and outlawing employment discrimination.

- The Voting Rights Act of 1965: Outlawed discriminatory voting practices like literacy tests and poll taxes, leading to a dramatic increase in African American voter registration and political participation.

The Lingering Legacy

While Jim Crow laws were legally abolished, their legacy continues to shape American society. Decades of systemic discrimination created profound disparities in wealth, education, housing, and healthcare that persist today. The psychological wounds of generations subjected to such dehumanization are not easily healed. Moreover, the tactics of voter suppression and the rhetoric of racial division, while no longer explicitly "Jim Crow," echo the mechanisms of that dark era.

The story of Jim Crow is a stark reminder of the fragility of democracy and the constant vigilance required to uphold the principles of equality and justice. It is a chapter of American history that reveals the depths of human prejudice but also the incredible resilience, courage, and unwavering spirit of those who fought to dismantle an iron cage and, in doing so, moved a nation closer to its stated ideals. To understand Jim Crow is not just to learn history; it is to understand the roots of many contemporary challenges and to affirm the enduring importance of civil rights for all.