The Katy’s Iron Veins: How the MKT Railroad Forged the American Southwest

In the sprawling tapestry of American history, where the threads of progress were often spun from steel and steam, few names resonate with the unique blend of frontier grit, financial drama, and enduring legacy quite like the Missouri-Kansas-Texas Railroad, affectionately known as "The Katy." For over a century, the Katy’s iron veins pulsed through the heart of the Southwest, carving pathways through untamed wilderness, fueling boomtowns, and connecting disparate communities. From its audacious beginnings as a post-Civil War dream to its eventual absorption into a modern rail giant, the Katy’s journey is a compelling saga of ambition, resilience, and the relentless march of industrialization.

A Vision Forged in the Aftermath of War (1865-1870)

The story of the Katy begins in the immediate aftermath of the American Civil War, a period of immense national reconstruction and westward expansion. In 1865, a group of visionary entrepreneurs, recognizing the strategic importance of linking the burgeoning Midwest with the resource-rich, yet underdeveloped, lands to the south, chartered the Union Pacific Railway, Southern Branch. Their ambition was nothing short of monumental: to build a railroad that would traverse Kansas, push through the unorganized Indian Territory (modern-day Oklahoma), and ultimately reach the Gulf of Mexico. This was a grand scheme, one that promised to unlock vast agricultural lands, facilitate cattle drives, and tap into mineral wealth.

The challenge was formidable. Indian Territory, then largely the domain of the Five Civilized Tribes (Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole), was not easily traversed. Treaties had to be negotiated, and the very concept of a railroad slicing through ancestral lands was met with both hope and apprehension. Yet, the federal government, keen on solidifying its presence and encouraging development, offered generous land grants to incentivize construction. The race was on.

The Race for Indian Territory: A Historic First (1870-1871)

By the late 1860s, the Union Pacific Southern Branch, soon to be renamed the Missouri-Kansas-Texas Railway, was locked in a fierce competition with the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad to be the first to lay tracks across the Kansas border into Indian Territory. The stakes were high: the first railroad to reach this frontier would secure invaluable land rights and a significant competitive advantage.

It was a grueling endeavor. Crews battled harsh weather, rough terrain, and the logistical nightmares of supplying men and materials in the wilderness. But on June 6, 1870, a pivotal moment arrived. The Katy, under the leadership of its energetic president, Levi Parsons, officially became the first railroad to enter Indian Territory, crossing the border south of Chetopa, Kansas. This was not merely an engineering feat; it was a symbolic act, a harbinger of the profound changes that would sweep across the plains. As historian H. Craig Miner noted in his work on the subject, "The Katy brought the outside world, in its most tangible form, to the Indian Nations."

The advance was swift. By December 1872, the Katy had reached Denison, Texas, having traversed the entire length of Indian Territory. This accomplishment fundamentally altered the economic landscape of the Southwest. Cattle, previously driven hundreds of miles along dusty trails like the Chisholm Trail, could now be loaded onto rail cars, dramatically reducing costs and time to market. Towns like Parsons, Kansas (named after the president), Vinita, Oklahoma, and Denison, Texas, sprang up along the line, transforming from sleepy hamlets into bustling rail hubs.

The Gould Years and Financial Turmoil (Late 19th Century)

Despite its initial success, the Katy’s journey was far from smooth. The late 19th century was an era of cutthroat competition, financial panics, and the rise of railroad titans. One such titan was Jay Gould, a notoriously shrewd and often ruthless financier who, by the 1880s, had acquired a controlling interest in the MKT. Gould’s philosophy was consolidation and efficiency, and he sought to integrate the Katy into his vast railroad empire, which included the Missouri Pacific.

Under Gould’s influence, the Katy expanded its network, reaching into new territories in Texas and establishing connections that solidified its position as a major regional player. However, Gould’s management style, focused heavily on profit and stock manipulation, often left the railroad’s infrastructure vulnerable. The Katy frequently found itself in financial distress, a common fate for many railroads during this volatile period, swinging between expansion and receivership. Its tracks were often criticized as being less well-maintained than those of its wealthier competitors, earning it the occasional derisive nickname "Poor Old Katy."

The Oil Boom and a Lifeline (Early 20th Century)

The early 20th century brought a new source of prosperity and a lifeline for the Katy: oil. The discovery of vast oil fields in Oklahoma and Texas, beginning with the Glenn Pool strike in 1905 and subsequent booms, transformed the regional economy. The Katy, with its extensive network through these very states, was perfectly positioned to capitalize on this new industry.

Tank cars filled with crude oil, equipment for drilling, and the countless supplies needed for boomtowns now flowed along the Katy’s lines. The railroad played a critical role in developing the energy infrastructure of the Southwest, connecting production sites to refineries and markets. This influx of freight traffic provided a much-needed financial boost, helping the Katy weather economic downturns and allowing for significant upgrades to its rolling stock and infrastructure.

From Prosperity to Depression and War (1920s-1940s)

The Roaring Twenties saw a period of relative stability and prosperity for the Katy. Passenger service, though never its primary focus, was robust, with trains like the "Katy Flyer" and the "Texas Special" connecting cities like St. Louis, Kansas City, and San Antonio. These trains, with their Pullman cars and dining services, offered a touch of elegance and convenience to travelers traversing the vast distances of the Southwest.

However, the good times were short-lived. The Great Depression hit the railroad industry hard. Freight volumes plummeted, and passenger revenues dwindled. The Katy, like many other railroads, was forced to implement drastic cost-cutting measures, defer maintenance, and lay off employees. It was a struggle for survival, a testament to the resilience of its workforce and management that it emerged from this era still intact.

World War II brought a dramatic reversal of fortunes. The railroads became the backbone of the war effort, transporting troops, munitions, and raw materials across the country. The Katy’s strategic lines through the industrial heartland and to military bases in Texas and Oklahoma saw unprecedented traffic. Locomotives and cars, once idled, now ran around the clock, pushing the aging infrastructure to its limits. This wartime boom provided the capital needed for modernization, paving the way for the transition from steam to diesel locomotives in the post-war era.

The Diesel Age and the Winds of Change (1950s-1970s)

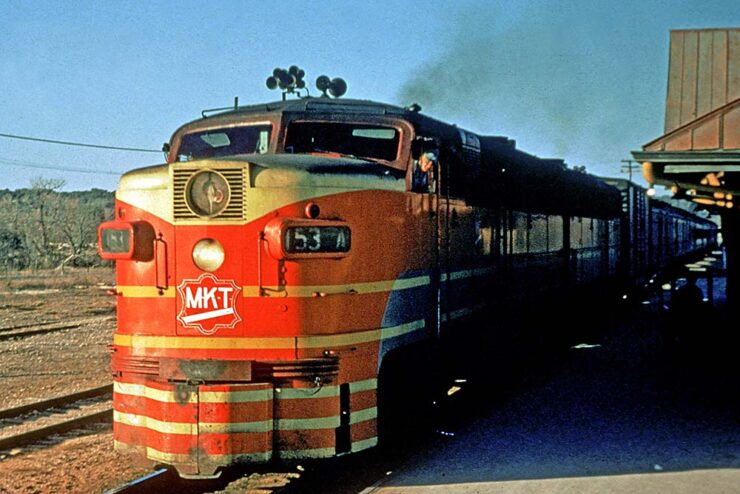

The post-war period ushered in the diesel age, a transformative era for the railroad industry. The Katy, like its competitors, began phasing out its iconic steam locomotives in favor of more efficient and powerful diesel-electric engines. This modernization improved operational efficiency and reduced costs, but it also coincided with significant challenges.

The rise of the Interstate Highway System and the trucking industry began to chip away at the railroads’ dominance in freight transportation, particularly for less-than-carload (LCL) shipments. Air travel also started to capture a significant share of the passenger market. The Katy’s passenger service, once a point of pride, became increasingly unprofitable. The "Texas Special," a joint operation with the St. Louis-San Francisco Railway ("Frisco"), made its final run in 1964. By 1965, the Katy had completely exited the passenger business, a mournful end to an era.

Throughout the 1960s and 70s, the Katy struggled to adapt. It experimented with innovations like "piggyback" service (transporting truck trailers on flatcars) and focused on bulk commodities like grain, coal, and chemicals. However, its relatively light traffic density and aging infrastructure, a legacy of its earlier financial woes, put it at a disadvantage against wealthier, more robust competitors like the Santa Fe and Union Pacific. Merger talks with other struggling lines, including the Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific (Rock Island) and the Illinois Central Gulf, never materialized, leaving the Katy to face an uncertain future alone.

The Final Chapter and Enduring Legacy (1980s and Beyond)

By the 1980s, the landscape of the American railroad industry was dominated by a wave of consolidation. Smaller, regional railroads were being absorbed by larger transcontinental giants. The Katy, though still an independent entity, found itself increasingly vulnerable. Its valuable routes into Texas and its connections to the Gulf Coast were attractive assets for a larger railroad looking to expand its reach.

In 1988, the inevitable occurred. The Missouri-Kansas-Texas Railroad was acquired by the Union Pacific Railroad, ending 123 years of independent operation. The Katy’s distinct identity, its red and yellow locomotives, and its unique culture were absorbed into the vast Union Pacific system. While many of its lines continue to be vital arteries for freight today, the name "Katy" as an operating railroad ceased to exist.

Yet, the Katy’s legacy endures in more than just the tracks still humming with freight. Perhaps its most beloved and tangible monument is the Katy Trail State Park in Missouri. Following the abandoned right-of-way of the former railroad, this rails-to-trails project transformed over 240 miles of track into the longest developed rail-trail in the United States. It’s a testament to the railroad’s initial vision, now offering hikers, bikers, and nature enthusiasts a unique pathway through the heart of Missouri, connecting small towns and scenic landscapes just as the trains once did.

The Katy’s story is a microcosm of American enterprise: a tale of bold ambition, fierce competition, boom and bust cycles, and the relentless drive for progress. From its pioneering push into Indian Territory to its vital role in the oil boom and its eventual absorption, the Missouri-Kansas-Texas Railroad was more than just steel and steam; it was a fundamental force in shaping the American Southwest, leaving an indelible mark on its geography, its economy, and its spirit. The echoes of its whistle may have faded, but the "Katy’s Iron Veins" continue to trace a path through history, a reminder of the railroad’s profound and lasting impact.