The Little Blue River: A Lifeline Through Kansas City’s Urban Core

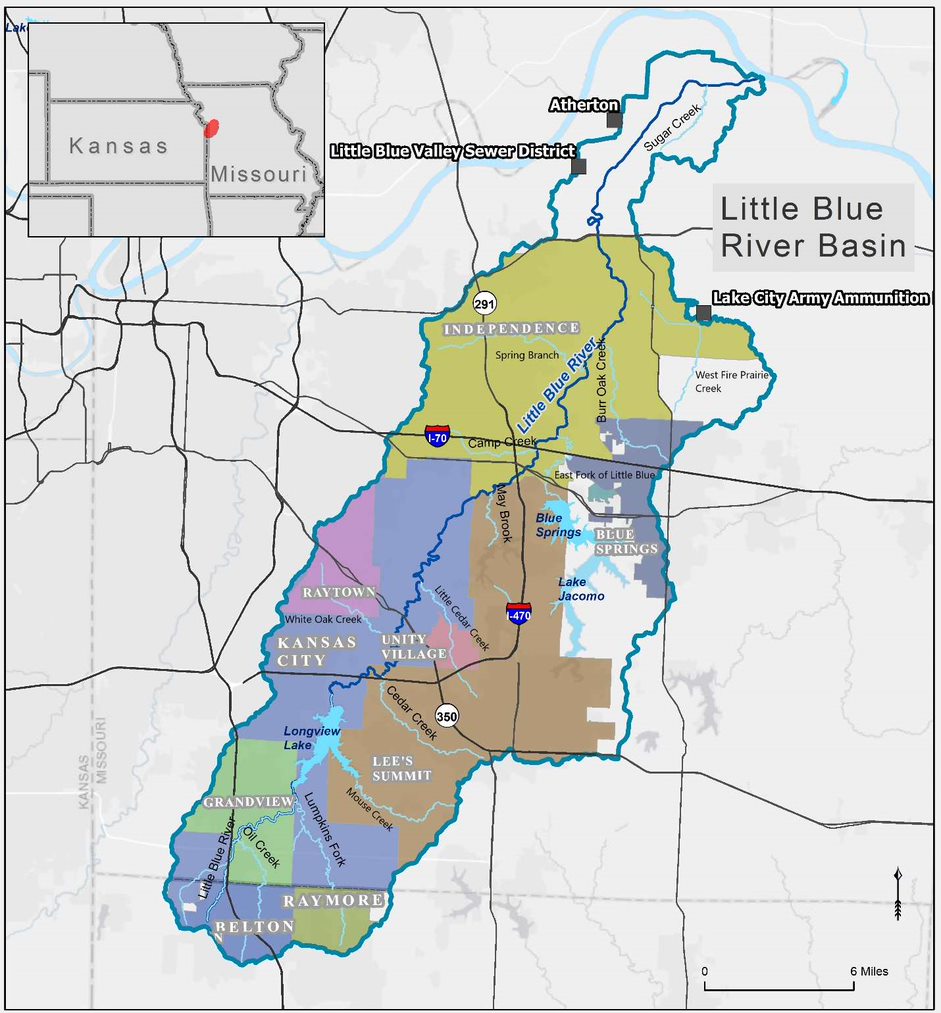

Often overshadowed by its mighty confluence partner, the Missouri River, the Little Blue River winds its way through the heart of Jackson County, Missouri, a seemingly unassuming waterway with a surprisingly rich and complex story. From its humble headwaters in southern Jackson County, the Little Blue flows north for approximately 60 miles, carving a path through suburban sprawl, industrial parks, and cherished green spaces before finally merging with the Missouri River just northeast of Kansas City. It is a river that has witnessed centuries of human activity, from Native American settlements and pioneer trails to industrial boom and environmental decline, now experiencing a slow, arduous, but hopeful journey toward ecological restoration.

For generations, the Little Blue was more than just a stream; it was a vital artery. Long before European settlers arrived, its banks were home to various Native American tribes, including the Osage and Kansa, who relied on its waters for sustenance and travel. The river’s name itself, "Little Blue," is believed to be a translation of a Native American term, possibly referring to the blue-tinted clay found along its banks or the clear, blueish hue of its waters in contrast to the often-muddy Missouri.

As the 19th century dawned, the Little Blue gained new prominence as a landmark for westward expansion. The Oregon, Santa Fe, and California Trails all crossed or ran parallel to sections of the Little Blue, making its fordable points and reliable water supply crucial for weary pioneers. Wagons rumbled across its shallow depths, and campsites dotted its banks, offering a temporary respite before the arduous journey continued. It was a place of rest, reflection, and sometimes, a final resting place. Historic markers along its course today serve as quiet reminders of this era, whispering tales of ambition, hardship, and the relentless march of progress.

The turn of the 20th century brought a different kind of tide to the Little Blue. As Kansas City grew, so did the demands on its surrounding natural resources. The river’s floodplains, once fertile agricultural lands, became attractive sites for industrial development. Factories, meatpacking plants, and residential areas began to crowd its banks. With this rapid urbanization came the inevitable: pollution.

"For generations, the Little Blue was simply where we drew water, where we farmed, where we played," recalls Martha Johnson, a local historian whose family has lived near the river for over a century. "Its decline was a slow, sad story, a gradual accumulation of everything we poured into it. You didn’t realize what you had until it was nearly gone."

The river became a convenient dumping ground for industrial waste, agricultural runoff, and untreated sewage. Its clear, blueish waters turned murky, its banks became littered, and its aquatic life dwindled. The once vibrant ecosystem suffered immensely. Fish kills became common, and the rich biodiversity that once characterized the river system was severely depleted. The Little Blue, once a source of life and beauty, had become a conduit for waste, its natural charm buried under layers of neglect.

However, even as its waters became compromised, the Little Blue never entirely lost its spirit. Pockets of natural beauty persisted, and its floodplains continued to offer a vital green corridor through an increasingly developed landscape. Recognizing its intrinsic value, a movement began in the late 20th century to reclaim and restore the river.

One of the most significant achievements in this effort is the development of the Little Blue Trace Trail. Conceived in the 1970s and steadily expanded, this paved multi-use trail now stretches for over 15 miles along the river’s western bank, connecting various parks and natural areas. It offers residents and visitors alike a chance to reconnect with the river, whether for walking, jogging, cycling, or simply enjoying nature. The trail has become a vital community asset, drawing people back to a river they once turned their backs on.

"The Little Blue Trace Trail isn’t just about recreation; it’s about reconnecting people with their natural environment and understanding the interconnectedness of our urban systems," says David Smith, a park planner with Jackson County Parks + Rec. "When people walk or bike along the river, they start to see its potential, its resilience. That’s the first step towards true conservation."

Beyond recreational infrastructure, concerted efforts have been made to address the underlying issues of water quality. Local environmental groups, county and state agencies, and even the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) have initiated projects aimed at reducing pollution and restoring habitat. These efforts include:

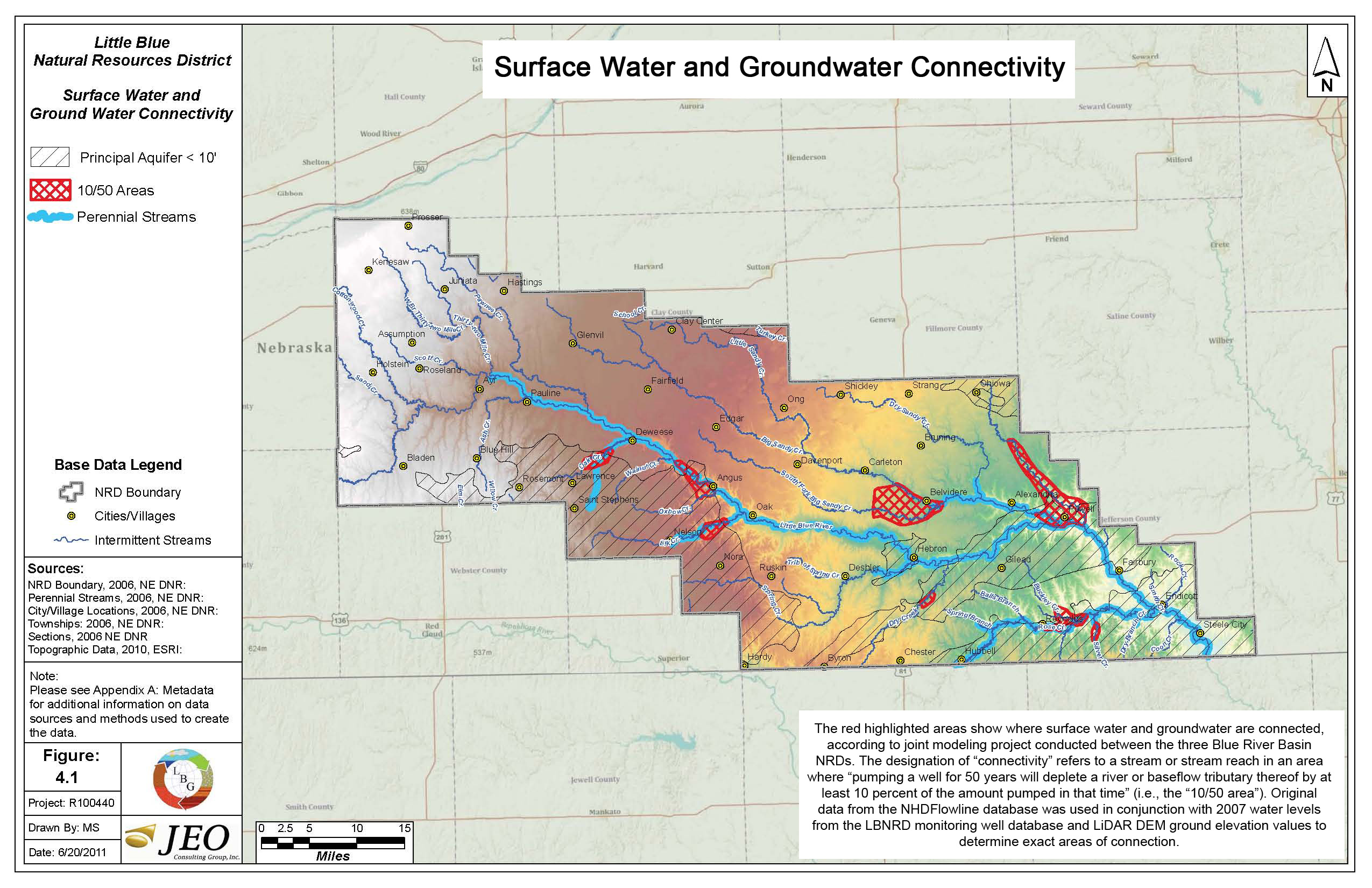

- Stormwater Management: Implementing green infrastructure like rain gardens, permeable pavements, and detention basins to filter runoff before it enters the river, reducing the influx of pollutants like oil, chemicals, and sediment from urban areas.

- Wastewater Treatment Upgrades: Modernizing and expanding wastewater treatment plants to ensure that effluent discharged into the river meets stringent quality standards.

- Agricultural Best Management Practices: Working with farmers in the upper watershed to implement practices that reduce fertilizer and pesticide runoff, such as riparian buffers and no-till farming.

- Stream Bank Stabilization: Using techniques like bioengineering (planting native vegetation) and riprap to prevent erosion, which adds sediment to the river and degrades aquatic habitats.

- Habitat Restoration: Creating and restoring wetlands, which act as natural filters and provide crucial habitat for birds, amphibians, and other wildlife. Volunteers frequently participate in tree planting events and trash cleanups, fostering a sense of community ownership and pride.

"The Little Blue is a microcosm of urban rivers everywhere," states Dr. Lena Hanson, an environmental scientist who has studied the river for decades. "It shows us that even heavily impacted waterways can be brought back, but it requires sustained effort, funding, and a fundamental shift in mindset from seeing rivers as waste conduits to recognizing them as vital ecological and recreational assets."

Despite these significant strides, the path to full recovery for the Little Blue is long and fraught with ongoing challenges. Non-point source pollution – diffuse pollution from widespread sources like agricultural fields and urban landscapes – remains a persistent problem, difficult to track and mitigate. The sheer volume of impervious surfaces in its watershed means that heavy rainfalls continue to bring surges of polluted runoff. Funding for long-term restoration projects is always a concern, as are the impacts of climate change, which can exacerbate flooding and drought conditions, further stressing the river’s ecosystem.

Moreover, the perception of the Little Blue as a "dirty" river, deeply ingrained from decades of neglect, is slow to change. Educating the public about the river’s improvements and encouraging responsible stewardship are ongoing battles.

Yet, there is an undeniable current of hope. The fish are slowly returning, native plant species are re-establishing themselves, and the river’s gentle murmur can once again be heard above the urban din. The Little Blue River, once a forgotten and abused waterway, is steadily reclaiming its identity as a valuable natural resource and a source of local pride.

It serves as a powerful testament to the resilience of nature and the transformative power of human effort. Its story is a living lesson in environmental stewardship, reminding us that even the most impacted landscapes can be healed with dedication and collective action. The Little Blue River, though "little" in name, carries a mighty message for Kansas City and beyond: that a healthy river is a healthy community, and that the future of our urban waterways depends on the choices we make today. As its waters continue their journey towards the Missouri, they carry not just the history of a region, but the promise of a more sustainable future.