/GettyImages-3246308-56de22933df78c5ba054568d.jpg)

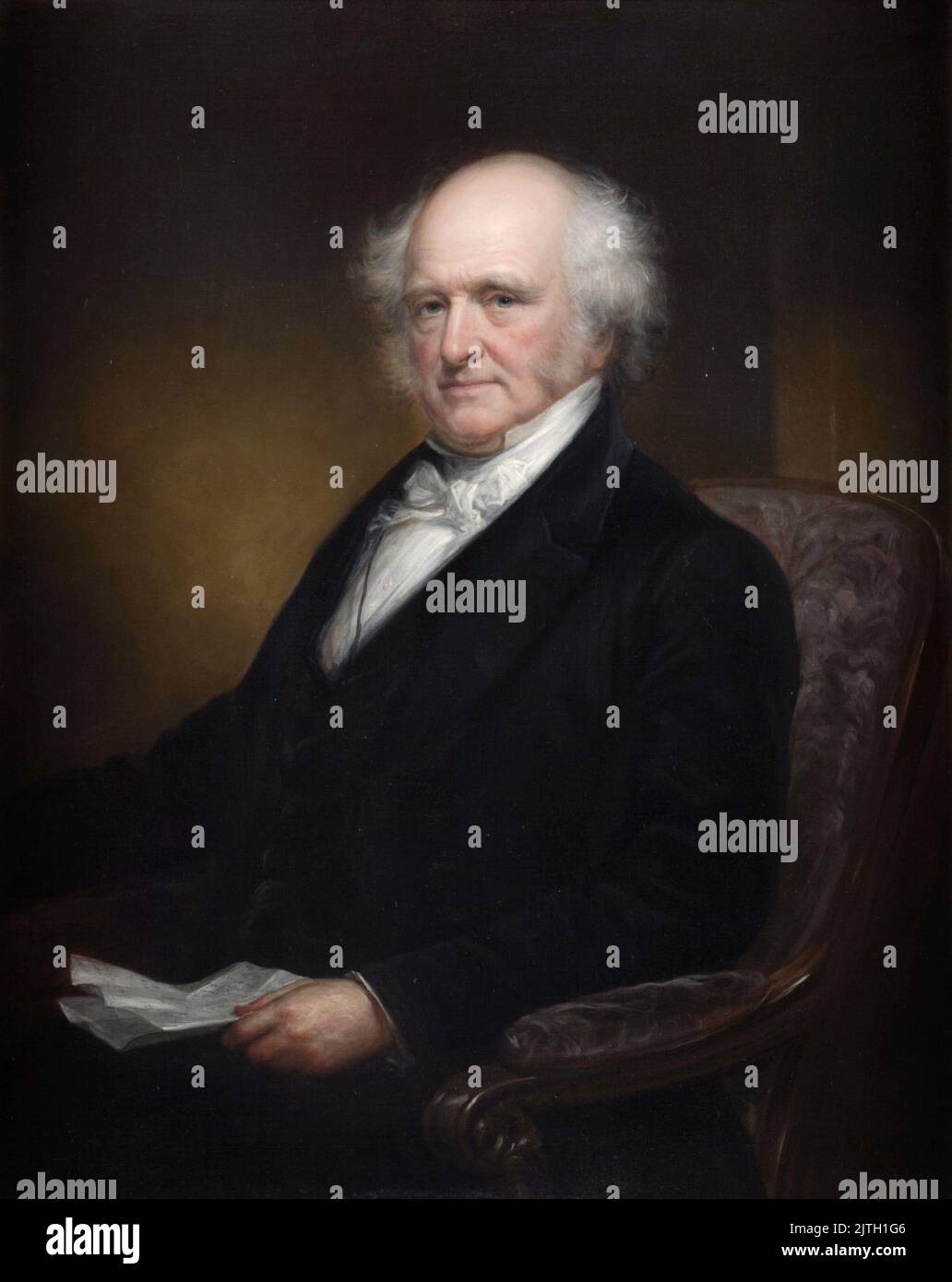

The Little Magician and the Great Panic: Martin Van Buren’s Enduring Enigma

He was, by all accounts, a political genius. A master strategist, an organizational wizard, and the architect of the modern American political party system. Yet, Martin Van Buren, the eighth President of the United States, is often relegated to the footnotes of history, remembered primarily for presiding over one of the nation’s most devastating economic crises. His presidency, a mere four years from 1837 to 1841, was a crucible that tested the very foundations of American governance, leaving behind a complex legacy of both profound political innovation and perceived leadership failure.

Born in Kinderhook, New York, in 1782, Van Buren was the first president not to have been born a British subject. His humble beginnings, as the son of a tavern keeper and farmer of Dutch descent, stood in stark contrast to the aristocratic lineages of many of his predecessors. Indeed, Dutch was his first language, a charming detail that underscores his distinctly American, self-made trajectory. Lacking the formal education of his contemporaries, Van Buren compensated with a razor-sharp intellect, an uncanny ability to read people, and an insatiable appetite for the intricate dance of politics.

His early career was a testament to his rising star. Admitted to the bar at age 20, he quickly established himself as a shrewd lawyer and a formidable political operator. He served in the New York State Senate, then as Attorney General of New York, and later as a U.S. Senator. It was during these years that Van Buren earned his famous nicknames: "The Little Magician" for his deft political maneuvering, and "The Red Fox of Kinderhook" for his cunning and often inscrutable nature.

/GettyImages-3246308-56de22933df78c5ba054568d.jpg)

Van Buren’s true genius lay not in oratory or charisma – he possessed neither in abundance – but in organization. He understood, perhaps better than anyone of his era, the need for a disciplined, national political party to unify disparate interests and achieve common goals. He meticulously built what became known as the "Albany Regency," a powerful political machine in New York that pioneered techniques like patronage, party loyalty, and systematic electioneering. This model would become the blueprint for the Democratic Party, which he helped forge into the dominant political force of its time.

His strategic brilliance brought him into the orbit of Andrew Jackson, the fiery "Old Hickory" who captivated the American populace. Van Buren became Jackson’s most trusted confidant, serving as Secretary of State and then as Vice President. He was a key member of Jackson’s "Kitchen Cabinet," advising on everything from Indian Removal to the Bank War. Their relationship, built on mutual respect and shared political principles, was instrumental in shaping the Jacksonian era. Jackson, ever loyal to those who served him well, handpicked Van Buren as his successor, famously declaring, "I have found him to be a true man, with no guile."

The stage was set for Van Buren’s ascent to the presidency in 1837, a seemingly triumphant culmination of his unparalleled political journey. Yet, fate, in the form of a catastrophic economic downturn, had other plans. Barely a month into his term, the Panic of 1837 erupted, plunging the nation into a deep and prolonged depression. Banks failed, businesses collapsed, unemployment soared, and agricultural prices plummeted. It was a perfect storm of factors: Jackson’s "Specie Circular" (which required payment for public lands in gold and silver), over-speculation in land, a cotton glut, and economic woes in Great Britain that curtailed demand for American goods.

Van Buren, the master strategist, found himself facing a crisis of unprecedented scale, one for which the existing governmental framework offered no easy solutions. Unlike his predecessors, who might have turned to a national bank for stabilization, Van Buren, a staunch advocate of limited government and a protégé of Jackson, was ideologically opposed to such an institution. He believed that government intervention in the economy should be minimal, and that the panic was, in part, a consequence of reckless speculation by private citizens.

His primary response was the proposal of the "Independent Treasury" system, also known as the "Sub-Treasury." This plan called for the federal government to separate itself entirely from private banks, collecting and disbursing its funds through its own vaults and sub-treasuries located in various cities. It was a radical idea for its time, designed to prevent future financial panics by insulating government finances from the speculative excesses of the private banking system.

The Independent Treasury was met with fierce opposition from the Whig Party, who advocated for a new national bank, and even from some within his own Democratic ranks. Critics argued that it would hoard specie, further constricting credit and prolonging the depression. It took Van Buren three years of relentless political struggle to finally get the Independent Treasury Act passed in 1840, a testament to his tenacity but also to the deep divisions the crisis engendered. While initially repealed by the Whigs, the Independent Treasury system would eventually be reinstated and would serve as the basis for the nation’s financial system until the creation of the Federal Reserve in 1913.

Beyond the economic turmoil, Van Buren’s presidency grappled with other significant challenges. He continued Jackson’s controversial policy of Indian Removal, notably overseeing the tragic "Trail of Tears," the forced relocation of the Cherokee Nation. He also navigated the complex legal and diplomatic waters of the Amistad case, where enslaved Africans mutinied on a Spanish ship. While Van Buren initially sided with the Spanish slave owners, the Supreme Court, with former President John Quincy Adams arguing for the Africans, ultimately ruled in their favor, a decision that underscored the growing national tension over slavery.

Despite his political brilliance, Van Buren struggled with public perception during the crisis. His refined tastes and elegant dress, which had earned him the derisive nickname "King Martin the First" from his opponents, seemed out of touch with a suffering populace. He became the scapegoat for the economic woes, unfairly blamed for a crisis whose roots predated his administration. The Whigs, a newly energized opposition party, effectively capitalized on public discontent, using slogans like "Tippecanoe and Tyler Too" to rally support for William Henry Harrison, a war hero with a folksy image.

In the 1840 election, Van Buren suffered a resounding defeat, securing only 60 electoral votes to Harrison’s 234. It was a bitter end to a presidency that had been consumed by crisis. He was, ironically, the first incumbent president to seek re-election and lose since John Adams in 1800, marking a significant shift in American political dynamics.

Yet, Van Buren’s story didn’t end with his defeat. He remained a formidable figure in Democratic politics, attempting to reclaim the presidency in 1844, only to be denied the nomination due to his opposition to the annexation of Texas, fearing it would expand slavery. In 1848, demonstrating his deep-seated anti-slavery sentiments, he broke with the Democratic Party over the issue of slavery’s expansion and ran for president as the candidate of the Free Soil Party. Though he didn’t win, his candidacy garnered enough votes to split the Democratic vote and contributed to Zachary Taylor’s victory, highlighting the burgeoning sectional crisis that would eventually lead to the Civil War.

Martin Van Buren retired to his estate, Lindenwald, in Kinderhook, New York, where he spent his final years writing his autobiography and observing the political landscape he had so profoundly shaped. He died in 1862, amidst the Civil War, a conflict he had long feared.

So, what is Van Buren’s enduring legacy? He is often overlooked, overshadowed by the larger-than-life figures of Jackson and Lincoln, and by the shadow of the Panic of 1837. Yet, his contributions were significant. He stabilized and legitimized the two-party system, demonstrating that a peaceful transfer of power could occur between organized, competing factions. He solidified the Democratic Party, creating a durable political machine that would dominate American politics for decades. His Independent Treasury, though controversial, was a foundational step towards a more stable and less speculative national financial system.

Perhaps Van Buren’s most significant, if underappreciated, contribution was his commitment to party politics as a mechanism for democratic governance. He understood that in a sprawling republic, political parties could serve as vital channels for aggregating public opinion, formulating policy, and ensuring accountability. He was, in essence, the father of modern American political organization.

Martin Van Buren remains an enigma – "The Little Magician" who could conjure political victories out of thin air, yet was powerless against the economic maelstrom that defined his presidency. He was a man of quiet organizational genius, whose impact on the structure of American democracy far outlasted the difficult four years he spent in the White House. His story reminds us that even presidents who preside over periods of great difficulty can leave behind legacies of profound, if sometimes unacknowledged, importance.