The Long Retreat: A Nation’s Desperate Flight for Freedom

By [Your Name/Journalist Name]

In the vast, untamed expanse of the American West, where towering mountains met sweeping plains, a chilling silence once fell over the landscape. It was the summer of 1877, a year etched into the annals of history not by grand declarations, but by the desperate, defiant footsteps of a people fleeing for their lives. This was the Nez Perce War, a conflict born of broken promises and the insatiable westward push, culminating in one of the most remarkable and tragic retreats in military history. It was a saga of courage, endurance, and ultimately, heart-wrenching surrender, encapsulated in the immortal words of Chief Joseph: "From where the sun now stands, I will fight no more forever."

The roots of the conflict stretch back decades, long before the first shot was fired. The Nez Perce, or Nimiipuu as they called themselves – meaning "The People" – were a sophisticated and peaceful nation whose ancestral lands spanned parts of what are now Oregon, Washington, and Idaho. Renowned for their selective breeding of the Appaloosa horse, their salmon fishing, and their intricate knowledge of the land, they had maintained generally good relations with American explorers and settlers for decades, famously aiding Lewis and Clark in 1805.

However, the discovery of gold in Nez Perce territory in 1860 irrevocably altered this fragile peace. The influx of miners and settlers led to intense pressure on the U.S. government to acquire more land. The Treaty of 1855 had established a large reservation encompassing much of their traditional lands. But in 1863, a new treaty, drastically reducing the reservation to a mere tenth of its original size, was presented. While some Nez Perce chiefs, known as the "Treaty Nez Perce," signed under duress or misunderstanding, several bands, including those led by Chief Joseph (Hinmatóowyalahtq̓it, or "Thunder Rolling Down the Mountain"), Looking Glass, White Bird, and Toohoolhoolzote, refused to sign. They were known as the "Non-Treaty Nez Perce," and they steadfastly maintained their right to their ancestral lands, particularly the fertile Wallowa Valley in Oregon, which Joseph’s band called home.

"My father," Chief Joseph would later recall, "said, ‘Always remember that your country was made for you by the Great Spirit and that you must never give it to any man.’ I remembered his words."

For years, a tense stalemate prevailed. General Oliver O. Howard, known as the "Christian General" and a Civil War veteran, was tasked with enforcing the 1863 treaty. Though he initially sympathized with Joseph, orders from Washington were clear: the Nez Perce must move to the diminished reservation. In May 1877, General Howard issued an ultimatum: the non-treaty bands had 30 days to gather their people and livestock and relocate. Failure to comply would result in military action.

The move itself was fraught with difficulty. The Wallowa River was swollen, making crossings treacherous, and much of their livestock was lost. The enforced relocation, combined with the loss of their cherished homeland, fueled a simmering resentment. Just as they prepared to move to the reservation, a small group of young warriors, grieving the murder of a father and seeking revenge for past injustices, broke ranks. They attacked and killed several white settlers. This act, though condemned by the Nez Perce chiefs, ignited the war. The point of no return had been crossed.

General Howard immediately dispatched troops to quell the uprising. The Nez Perce, numbering around 750 – including some 200 warriors, with the rest being women, children, and elders – knew they could not defeat the U.S. Army in a conventional war. Their only hope was to escape to Canada, where they believed they could find refuge with Sitting Bull’s Sioux, who had fled there after the Battle of Little Bighorn the previous year. Thus began their epic, 1,170-mile flight for freedom.

The opening engagement was a stunning Nez Perce victory. On June 17, 1877, in the Battle of White Bird Canyon, a detachment of 100 U.S. cavalry under Captain David Perry, eager to avenge the settler killings, charged into a well-laid Nez Perce ambush. The warriors, led by Ollokot (Chief Joseph’s younger brother) and White Bird, inflicted heavy casualties, killing 34 soldiers while suffering no fatalities themselves. This initial triumph boosted Nez Perce morale but also sent a clear message to the U.S. military: this would be no easy campaign.

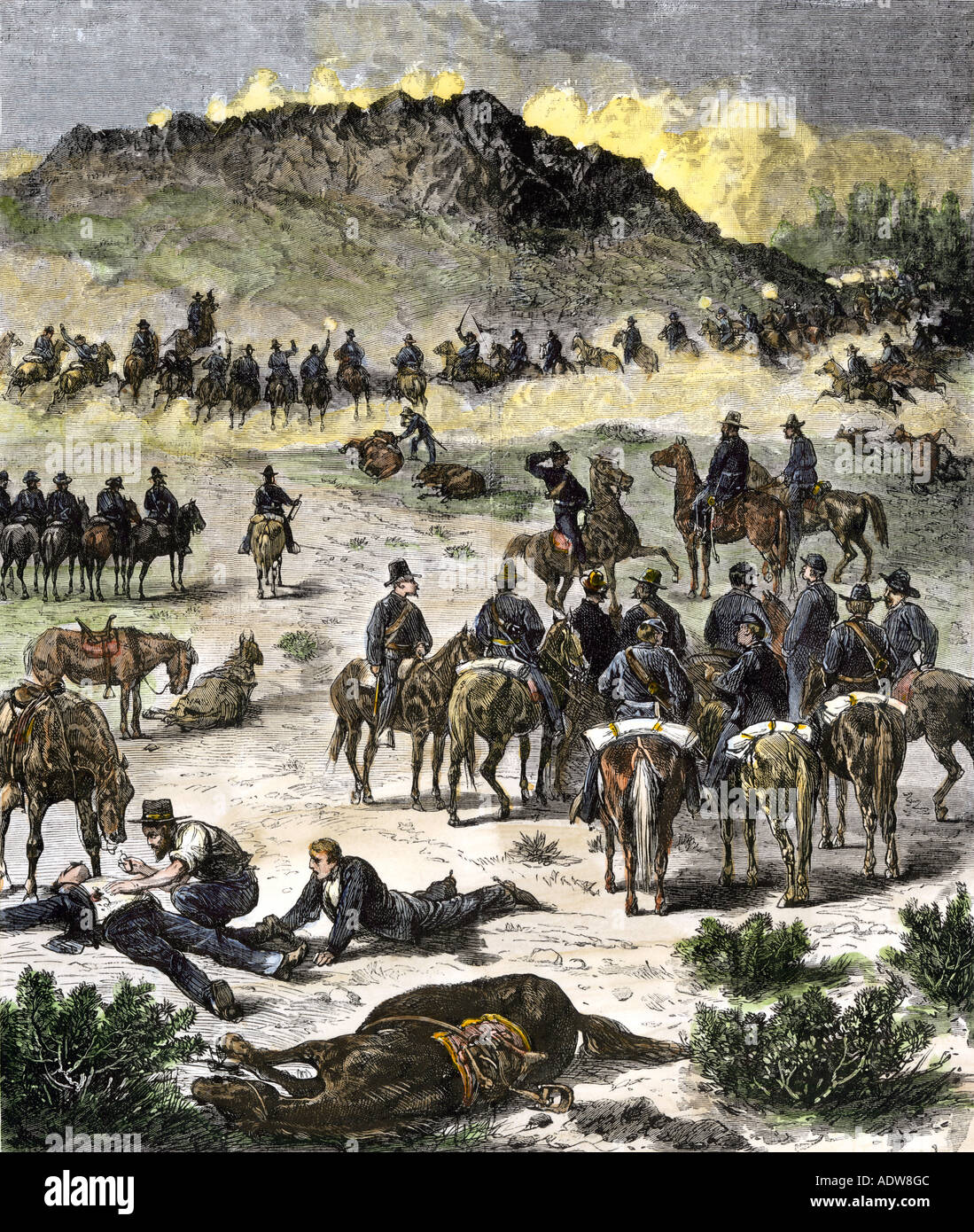

General Howard, humiliated by the defeat, mounted a relentless pursuit. The Nez Perce, masters of the terrain and superb horsemen, initially outmaneuvered him, employing sophisticated guerilla tactics and disciplined rear-guard actions. Their journey took them through rugged mountain passes, across vast plains, and over raging rivers. They often traveled at night, leaving false trails and employing decoys.

The next major engagement, the Battle of the Clearwater on July 11-12, was a more conventional fight. Howard’s forces, now numbering over 400, engaged the Nez Perce in a two-day battle. While the Nez Perce fought bravely and inflicted casualties, they were eventually forced to retreat, suffering their first significant losses and leaving behind many of their supplies. This battle marked a turning point; it became clear that direct confrontation with the larger, better-equipped U.S. Army was unsustainable.

The Nez Perce then embarked on their most audacious maneuver: crossing the rugged Bitterroot Mountains via the Lolo Trail, a notoriously difficult passage. They aimed for Montana, hoping to bypass Howard and find a path to Canada. Along the way, they encountered Montana volunteers at Fort Fizzle, a hastily constructed barricade. Through shrewd negotiation and a display of force, Chief Joseph convinced the Montanans to allow them passage, promising not to harm settlers if they were not provoked. For a brief period, they bought supplies and engaged in peaceful trade, a testament to their desire for peace even amidst war.

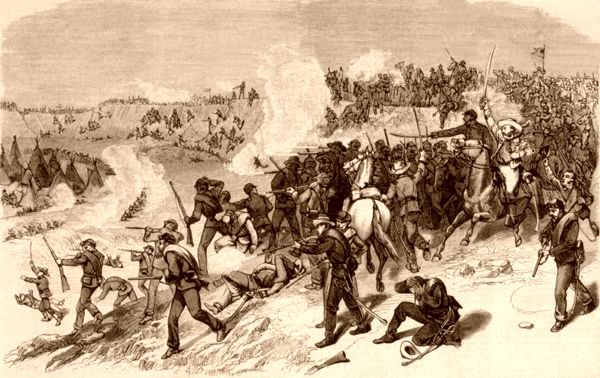

This fragile truce ended abruptly. On August 9, as the Nez Perce rested at Big Hole Basin, General John Gibbon, leading an element of the U.S. Army from Fort Shaw, launched a devastating dawn surprise attack. The battle was a horrific slaughter, particularly of women and children in their tipis. The Nez Perce, though caught off guard, rallied with incredible bravery, fighting fiercely to protect their families. "We were up before the sun," said Yellow Wolf, a Nez Perce warrior, "getting our morning meal. Then, like a clap of thunder, the shooting began." The Nez Perce eventually drove Gibbon’s forces into a defensive perimeter, but at a terrible cost: an estimated 60 to 90 Nez Perce lives were lost, many of them non-combatants. The Big Hole Massacre became a brutal reminder of the war’s true stakes.

Despite the heavy losses, the Nez Perce pressed on, their resolve hardened. They continued their trek, now pursued by both Howard from the west and Gibbon’s battered but still formidable forces. In late August, they briefly entered Yellowstone National Park, where they encountered several groups of bewildered tourists, some of whom were taken captive for short periods before being released. This surreal encounter highlighted the stark contrast between the unfolding tragedy and the burgeoning American leisure class.

The pursuit intensified. Howard, despite his slow progress, was relentless. Colonel Nelson A. Miles, leading fresh troops from Fort Keogh, was ordered to intercept the Nez Perce as they approached the Canadian border. Miles, known for his aggressive tactics, moved swiftly to cut off their escape.

By late September, the Nez Perce were exhausted, their horses worn out, their supplies dwindling. They were less than 40 miles from the Canadian border when Miles’s cavalry caught them at Bear Paw Mountain in northern Montana. The Battle of Bear Paw began on September 30. For five grueling days, the Nez Perce, dug into shallow rifle pits, fought a desperate, final stand against a numerically superior and better-equipped force. The weather turned bitterly cold, with snow and freezing rain adding to their misery. Ollokot, Joseph’s beloved brother, was killed, as were many other warriors. The women and children shivered and starved in their exposed positions.

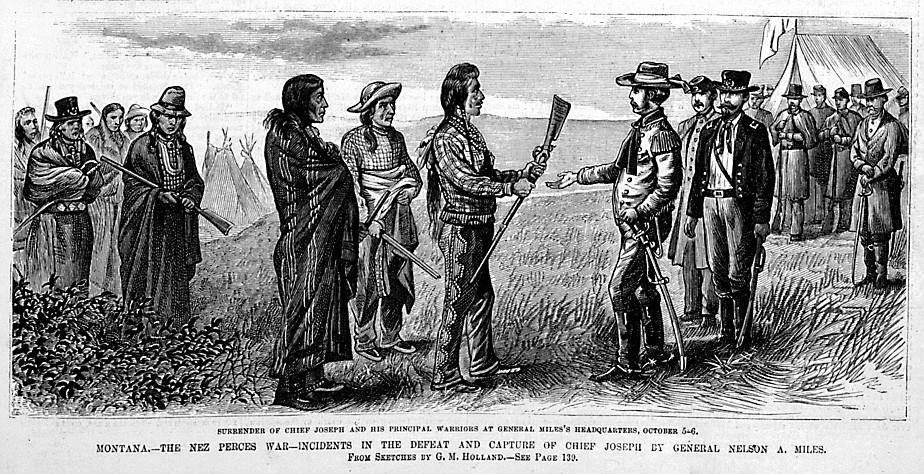

The fighting slowly ground to a halt. With his people freezing, starving, and surrounded, and with General Howard’s forces arriving to reinforce Miles, Chief Joseph faced an agonizing choice. On October 5, 1877, he rode out to surrender. His speech, delivered through an interpreter, became an enduring testament to his people’s suffering and his own profound weariness:

"Tell General Howard I know his heart. What he told me before, I have in my heart. I am tired of fighting. Our chiefs are killed. Looking Glass is dead. Toohoolhoolzote is dead. The old men are all dead. It is the young men who say yes or no. He who led on the young men is dead. It is cold, and we have no blankets. The little children are freezing to death. My people, some of them, have run away to the hills, and have no blankets, no food; no one knows where they are – perhaps freezing to death. I want to have time to look for my children, and see how many of them I can find. Maybe I shall find them among the dead. Hear me, my chiefs! I am tired. My heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands, I will fight no more forever."

This powerful declaration, often condensed to its poignant final line, conveyed the absolute exhaustion and despair of a people who had fought with incredible bravery against impossible odds. Joseph surrendered under the promise that his people would be allowed to return to their homeland in Oregon. It was a promise that was immediately broken.

Instead of being returned to Oregon, the surviving Nez Perce, numbering just over 400, were sent into exile, first to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, and then to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma), a climate vastly different and far less hospitable than their mountain home. Disease and despair ravaged them. Chief Joseph tirelessly campaigned for his people’s return, traveling to Washington D.C. and meeting with presidents and influential figures. His eloquence and dignity captivated the American public, but his pleas for justice largely fell on deaf ears.

It wasn’t until 1885, eight years after their surrender, that a small number of Nez Perce, including Chief Joseph, were allowed to return to the Pacific Northwest. However, they were not permitted to return to the Wallowa Valley. Instead, Joseph and his band were sent to the Colville Reservation in Washington, where he died in 1904, officially of a "broken heart," according to his doctor.

The Nez Perce War stands as a tragic and poignant chapter in American history. It was a conflict born of injustice and fueled by the relentless march of Manifest Destiny. The Nez Perce, through their extraordinary resilience, strategic brilliance, and the sheer force of their will, demonstrated a profound love for their land and their way of life. Their 1,170-mile odyssey, a desperate dash for freedom against overwhelming odds, remains a testament to the human spirit’s capacity for endurance in the face of insurmountable adversity. Chief Joseph’s words continue to resonate, a timeless lament for a lost world and a powerful reminder of the enduring cost of conquest.