The Long Road to Peace: Appomattox and the Unraveling of the Confederacy

The spring of 1865 was a season of profound reckoning for a nation torn asunder. For four agonizing years, the American Civil War had raged, carving an indelible scar across the landscape and the national psyche. As April dawned, the air hung heavy with the scent of gunpowder and the weight of immense human suffering, but also with a nascent hope for peace. It was against this backdrop that the final, decisive chapter of the conflict unfolded: the Appomattox Campaign, a relentless pursuit and a poignant surrender that would forever alter the course of American history.

The stage for Appomattox had been set over the preceding ten months. Ulysses S. Grant’s Union Army of the Potomac had relentlessly tightened its stranglehold around Petersburg and Richmond, the Confederate capital. The trench warfare had been brutal, the casualties staggering, but the strategic advantage was undeniably with the Union. By late March 1865, the Confederate lines were stretched thin, their soldiers starving, their morale shattered. Grant, ever the pragmatist, knew the end was near and launched his final offensive.

On April 1st, at the Battle of Five Forks, Major General Philip Sheridan’s Union cavalry, supported by infantry, shattered the Confederate right flank, commanded by Major General George Pickett. This decisive Union victory rendered Petersburg and Richmond indefensible. Robert E. Lee, commanding the Army of Northern Virginia, knew his time was up. On the night of April 2nd, with a heavy heart, he ordered the evacuation of both cities, signaling the beginning of his desperate flight west.

The Desperate Flight: Lee’s Last Gamble

Lee’s strategic objective was clear, if increasingly improbable: escape the Union encirclement, march west along the Appomattox River, link up with supply trains at Amelia Court House, and then proceed south to unite with General Joseph E. Johnston’s forces in North Carolina. This was a desperate gamble, a last, faint hope to prolong the war and perhaps secure more favorable terms.

However, Grant was not one to allow an enemy to escape. His pursuit was immediate, relentless, and perfectly coordinated. The Union forces, now numbering over 100,000 men, were well-fed, well-equipped, and buoyed by the scent of victory. They moved with a speed and determination that Lee’s emaciated and exhausted troops, numbering barely 30,000, could not match.

The initial days of the retreat were a testament to the Confederates’ dwindling strength. Lee’s plan for supplies at Amelia Court House went awry; instead of the anticipated food, only ammunition wagons awaited them. This critical failure meant the army had to forage for sustenance in an already depleted countryside, further slowing their progress and deepening their despair. Many soldiers, their uniforms tattered, their stomachs empty, simply dropped their weapons and vanished into the woods, choosing the uncertain hope of home over the certainty of continued suffering.

The Grinding Pursuit: Battles of Attrition

The Appomattox Campaign was not a single grand battle but a series of brutal skirmishes and forced marches. Each engagement further chipped away at Lee’s dwindling strength and hope.

One of the most devastating blows came on April 6th, at the Battle of Sailor’s Creek. Here, a significant portion of Lee’s retreating army, including many high-ranking officers and thousands of men, was cut off and captured by Union forces under Sheridan and Major General George Crook. It was a calamitous defeat; over 7,000 Confederates, including eight generals, were taken prisoner. Lee watched from a nearby ridge as his army dissolved, reportedly exclaiming, "My God, has the army dissolved?" This moment marked a critical psychological turning point, even for the stoic Lee.

Following Sailor’s Creek, Lee continued his desperate westward push, attempting to cross the Appomattox River at High Bridge. He managed to burn the bridges behind him, momentarily stalling the Union pursuit, but the respite was brief. Union engineers quickly repaired a portion of the bridge, and the chase resumed.

On April 7th, at Farmville, Lee’s exhausted troops made a final, futile attempt to find sustenance and briefly fended off Union attacks. But the pressure was immense. Grant, sensing the end, sent a direct letter to Lee that day, requesting his surrender to "stop further effusion of blood." Lee, ever the dignified soldier, acknowledged the letter but parried, suggesting he did not yet consider his army "so circumstanced as to render its surrender necessary." It was a final, forlorn hope for a strategic advantage that no longer existed.

The Final Blockade: Appomattox Court House

By April 8th, Lee’s army was utterly spent. They had marched nearly 100 miles in six days, fighting rear-guard actions, constantly harassed by Union cavalry. Their last hope for supplies lay at Appomattox Station, where trains carrying rations awaited them. But Grant had anticipated this. Sheridan’s cavalry, having outflanked Lee, had already reached the station and captured the precious supply trains.

When Lee’s advance units reached Appomattox Court House on the morning of April 9th, expecting to find the road clear, they were met instead by a formidable line of Union cavalry, soon to be reinforced by infantry under Major General Edward Ord, who had marched an incredible 30 miles overnight. The road ahead was blocked. Lee ordered a final, desperate charge to break through, but it was quickly repulsed. Union infantry then began to deploy, confirming the grim reality. Lee’s army was surrounded.

"There is nothing left for me to do but to go and see General Grant, and I would rather die a thousand deaths," Lee reportedly told his aides. The proud general, whose military brilliance had sustained the Confederacy for so long, finally acknowledged the inevitable. He sent a note to Grant, requesting a meeting to discuss the terms of surrender.

The Meeting: A Tableau of History

The meeting between the two great commanders took place on Palm Sunday, April 9, 1865, in the modest parlor of Wilmer McLean’s house in Appomattox Court House. The setting itself holds a poignant historical footnote: McLean had moved to Appomattox from Manassas to escape the war, only to have it end in his new home.

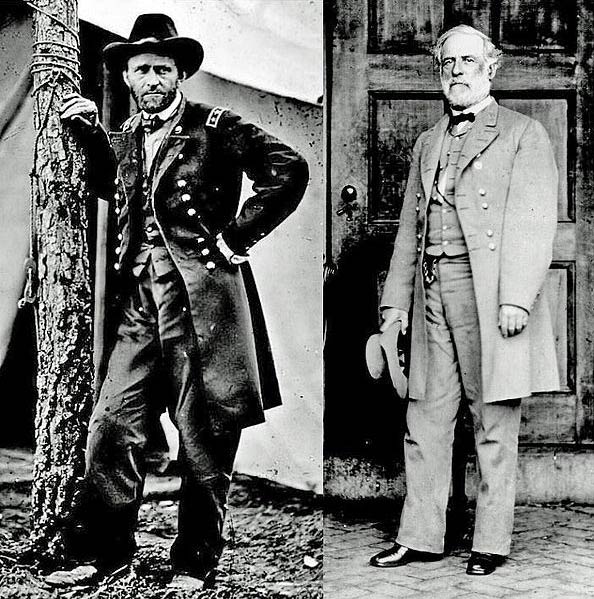

Grant arrived first, accompanied by his staff, dressed simply in a mud-splattered private’s uniform, identifiable only by his shoulder straps. Lee followed, immaculate in his pristine gray uniform, polished boots, and a dress sword, a stark contrast that spoke volumes about their respective circumstances and personalities.

The initial moments were filled with an awkward silence. Grant later recalled in his memoirs, "I felt like anything rather than rejoicing at the downfall of a foe who had fought so long and valiantly, and had suffered so much for a cause, though that cause was, I believe, one of the worst for which a people ever fought, and one for which there was the least excuse." The two men, who had faced each other across battlefields for years, now sat as symbols of a nation’s agony and its impending healing.

Their conversation began with reminiscences of their brief encounter during the Mexican-American War. Only then did they turn to the grim business at hand. Grant, known for his generosity in victory, offered remarkably lenient terms. Confederate soldiers would be paroled, allowed to return home, and would not be prosecuted for treason. Officers could keep their sidearms, and, crucially, all soldiers who owned horses or mules could take them home "to put in a crop." This last provision, proposed by Grant, was a compassionate gesture aimed at helping the defeated soldiers rebuild their lives and avoid starvation, acknowledging that the nation would need their labor to recover.

Lee, deeply moved by Grant’s magnanimity, accepted the terms. He expressed his gratitude for the "liberal" conditions, understanding that they offered a path toward reconciliation rather than retribution. The surrender document was signed, and with a handshake, the official end of the Army of Northern Virginia, and effectively the Confederacy, was sealed.

The Aftermath: Silence, Tears, and Reconciliation

As news of the surrender spread, the reaction was immediate and profound. Among the Union troops, there was an initial burst of triumphant cheering, but Grant swiftly put an end to it, stating, "The war is over. The rebels are our countrymen again." It was a powerful message of reconciliation, setting the tone for the difficult process of reuniting the fractured nation.

For the Confederate soldiers, the moment was one of profound sorrow and despair. Tears flowed freely as they stacked their arms, folded their battle flags, and received their paroles. Many struggled to comprehend the finality of their defeat, their long struggle ending not with glory, but with the quiet dignity of surrender.

On April 12th, the formal surrender ceremony took place. Major General Joshua L. Chamberlain, the hero of Little Round Top, commanded the Union troops who received the stacking of arms. As the Confederates marched past, Chamberlain ordered his men to salute, a gesture of respect for their brave but defeated adversaries. Brigadier General John B. Gordon, leading the Confederate column, returned the salute, a moment of profound mutual respect that transcended the bitterness of war. It was a powerful symbol of the potential for healing.

The Legacy of Appomattox

The Appomattox Campaign was more than just the end of a war; it was the beginning of a nation reborn. It preserved the Union, abolished slavery, and set the stage for the long and arduous process of Reconstruction. Grant’s magnanimous terms of surrender laid a crucial foundation for national healing, preventing a prolonged guerrilla war and fostering a spirit of reunion rather than vengeance.

Lee, despite his defeat, emerged from Appomattox with his honor intact. He went on to become the president of Washington College (now Washington and Lee University), dedicating his post-war life to education and reconciliation, urging his fellow Southerners to accept the outcome and rebuild.

The events of April 1865 at Appomattox Court House remain one of the most poignant and significant moments in American history. It was a testament to the enduring human cost of conflict, the resilience of the human spirit, and the power of leadership – both in victory and defeat – to shape the future of a nation. The long road to peace had been paved with blood and sacrifice, but it ultimately led to a fragile, yet enduring, reunification of the United States of America.