The Lords of the Shell: Unearthing the Lost Empire of Florida’s Calusa

On the southwestern coast of Florida, where the Gulf of Mexico kisses a labyrinth of mangroves and estuaries, a powerful and enigmatic civilization once held sway. For centuries before European contact, and for over 200 years after, the Calusa tribe, often referred to as "the Shell Indians," carved out a formidable empire, defying conventional notions of pre-Columbian societies in North America. Unlike many complex cultures that relied on agriculture, the Calusa built their sophisticated chiefdom on the sheer bounty of the sea, crafting their world from the very shells that lined their abundant coasts. Their story is one of remarkable adaptation, fierce independence, and ultimately, a tragic disappearance, leaving behind monumental shell structures as silent testaments to a lost world.

An Empire Forged from Water

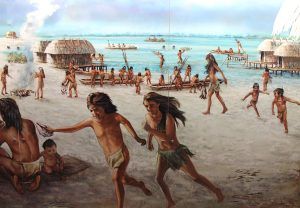

To understand the Calusa, one must first understand their environment. Southwest Florida is a watery realm of shallow bays, barrier islands, and intricate mangrove forests, teeming with marine life. This was not a land for farming; the sandy soils and fluctuating water levels made traditional agriculture impractical. Yet, it was a paradise for a people who mastered the art of living off the sea.

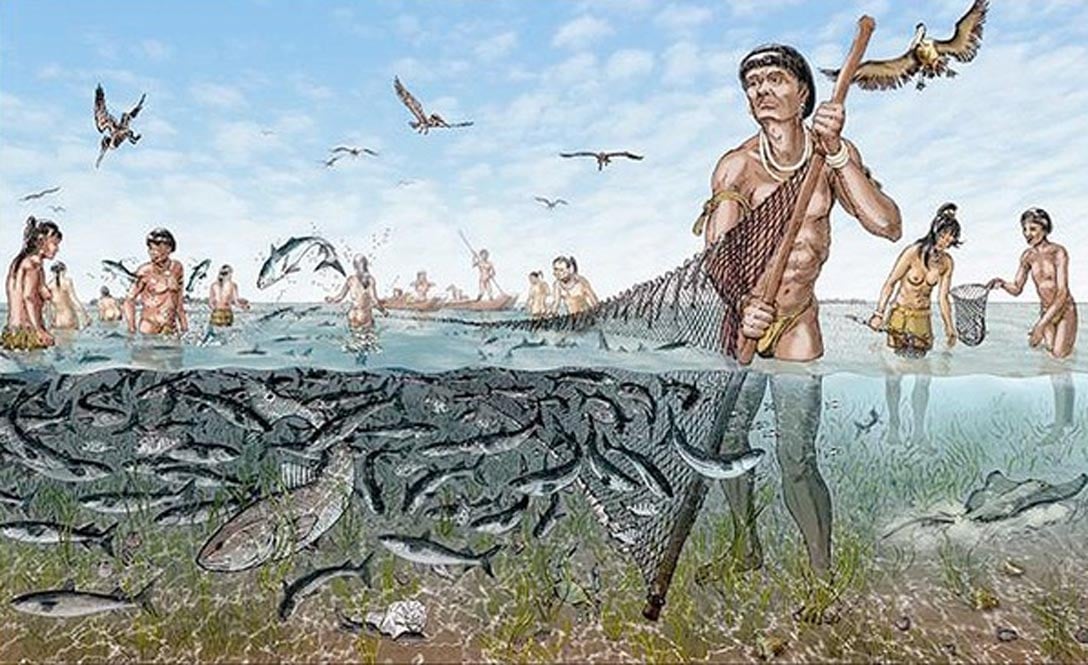

The Calusa were expert fishermen, divers, and navigators. Their diet consisted almost entirely of fish, shellfish, marine mammals like manatees, and various aquatic plants. They developed ingenious fishing techniques, including complex weir systems, nets woven from palm fibers, and bone-tipped spears. Their mastery of the waterways was unparalleled; they navigated vast distances in large canoes carved from cypress logs, some capable of carrying dozens of warriors or vast quantities of goods. This naval prowess allowed them to control a vast territory, extending their influence and trade networks deep into central Florida and across the Florida Keys, even reaching Cuba.

"They cultivate nothing," noted Hernando de Escalante Fontaneda, a Spaniard held captive by the Calusa for 17 years in the mid-16th century, "and they eat only fish." This observation, though perhaps an oversimplification, highlights the truly unique aspect of the Calusa: they were a complex, hierarchical society – a chiefdom – that achieved its power and stability without the agricultural foundations that characterized civilizations like the Maya, Aztec, or even the Mississippian mound builders to their north.

Society and Structure: A Chiefdom of Power

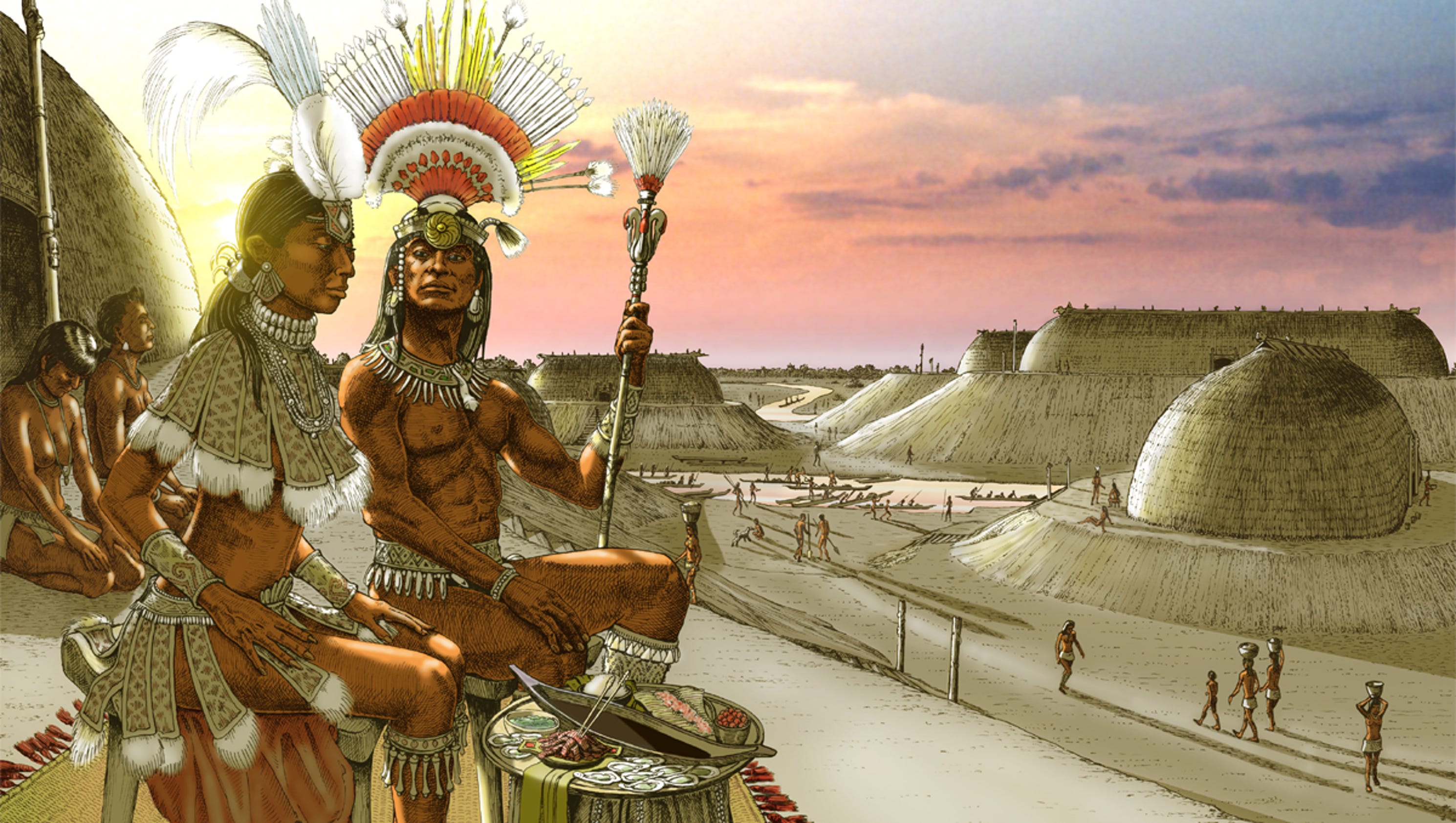

At the apex of this stratified society stood the cacique, or chief, known as Calos by the Spanish, a title that eventually gave the tribe its name. The chief held immense power, both political and spiritual, presiding over a strict social hierarchy that included nobles, priests, commoners, and captives. The capital of their empire was believed to be at Mound Key, a massive artificial island constructed entirely from shells and other refuse, rising majestically from Estero Bay.

These aren’t just refuse piles; they are monumental expressions of power and permanence, some reaching heights of over 30 feet. Archaeologists like William Marquardt of the Florida Museum of Natural History have meticulously studied these sites, revealing complex architectural planning. "Mound Key was not just a village," Marquardt explains, "it was a ceremonial center, a residential area for the elite, and a symbol of Calusa power, built layer upon layer over centuries." The mounds provided protection from storm surges and elevated important structures like the chief’s dwelling and temples. Networked by sophisticated canals, these sites served as hubs for trade, ceremony, and defense.

The Calusa were also skilled artisans, particularly in wood carving. Though little has survived the humid Florida climate, Spanish accounts mention elaborately carved wooden masks, effigies of animals, and ceremonial objects, reflecting a rich spiritual life deeply connected to the natural world, particularly the animals of the sea and sky. Their religion was animistic, with a belief in three souls, one of which could wander and interact with the spiritual realm.

The Fierce Encounter: Spanish Arrival

The relative isolation of Florida’s southwestern coast meant the Calusa were among the last major Native American groups to encounter Europeans. That changed dramatically in 1513 when Juan Ponce de León, the first European to formally explore Florida, sailed into their waters. What followed was not a peaceful exchange but a brutal clash.

Ponce de León, seeking fresh water and a fabled Fountain of Youth, was met with a barrage of arrows from large Calusa war canoes. The Calusa, renowned for their martial prowess, met the conquistadors not with fear, but with fierce defiance. They quickly recognized the threat posed by these heavily armed strangers and responded with overwhelming force, driving Ponce de León and his men back to their ships. The Spanish accounts consistently portray the Calusa as formidable warriors, skilled archers, and unyielding in their defense of their territory.

Decades later, in the mid-16th century, the Spanish tried again. Pedro Menéndez de Avilés, founder of St. Augustine and Florida’s first governor, attempted a more diplomatic approach, seeking to convert the Calusa and establish a mission. He even managed to secure a marriage alliance between his nephew and the sister of Chief Carlos (the Spanish rendition of Calos), hoping to gain influence. However, this fragile peace quickly dissolved. The Calusa chief, shrewd and pragmatic, saw the Spanish as a means to an end – a source of valuable iron tools and weapons – but had no intention of abandoning his people’s traditions or submitting to foreign rule. Repeated attempts by the Spanish to impose their will were met with assassinations of missionaries and open revolt.

"The Calusa were a proud and independent people," notes historian Jerald T. Milanich, "They saw no reason to change their way of life or adopt Spanish religion. They were simply too strong to be easily conquered." Their resistance was a testament to their strength, organization, and a deep-seated desire to preserve their unique culture.

The Fading Echoes: Decline and Disappearance

Despite their fierce resistance and formidable power, the Calusa empire eventually crumbled. The primary culprit was not direct military defeat, but a far more insidious enemy: European diseases. Smallpox, measles, influenza – against which the Native Americans had no immunity – swept through their villages with devastating effect, decimating populations who had lived for millennia in relative isolation from such pathogens.

By the late 17th and early 18th centuries, the Calusa, already weakened by disease, faced a new and equally destructive threat: slave raids. English colonists from the Carolinas, often allied with Muskogean-speaking tribes like the Creek, launched devastating raids into Florida, capturing Native Americans to sell into slavery in the Caribbean or on plantations. The remaining Calusa, their numbers drastically reduced, were forced to abandon their ancestral lands, seeking refuge further south in the Florida Keys or attempting to integrate with other surviving groups.

By the mid-18th century, only a few hundred Calusa remained. Some may have eventually merged with the newly emerging Seminole and Miccosukee tribes, themselves a mix of various Creek, Hitchiti, and other refugees. The last recorded mention of the Calusa as a distinct group dates to the early 19th century, when a small band sought refuge in Cuba, fleeing the increasing pressures of American expansion. After thousands of years, the unique civilization of the Calusa vanished, leaving behind only their monumental shell mounds and the fragmented accounts of their Spanish adversaries.

A Lasting Legacy: Unearthing the Past

Today, what remains of the Calusa empire lies buried beneath the shifting sands and modern developments of Southwest Florida. Yet, their story continues to captivate archaeologists, historians, and the public. Sites like Mound Key, Pineland, and Big Mound Key offer invaluable insights into their daily lives, their engineering prowess, and their spiritual beliefs. Excavations continue to unearth artifacts – shell tools, pottery shards, occasional wooden carvings preserved in muck – that slowly piece together the puzzle of this enigmatic people.

The Calusa tribe stands as a powerful testament to human ingenuity and adaptation, demonstrating that complex societies could flourish even without agriculture, driven instead by a profound understanding and utilization of their natural environment. Their fierce independence and prolonged resistance to European colonization serve as a poignant reminder of the strength and resilience of Native American cultures.

While their language is lost and their direct descendants are no longer identifiable as a distinct group, the legacy of the Calusa endures in the very landscape of Southwest Florida. The shell mounds they built continue to define the coastline, silent sentinels to a powerful civilization that once commanded the waters, the "Lords of the Shell" who left an indelible mark on the history of the continent. Their story is a crucial chapter in the narrative of Florida, a powerful echo of a lost world that reminds us of the rich tapestry of human history that existed long before the arrival of Europeans.