The Man Who Bridged Worlds: The Enduring Legacy of George Bent

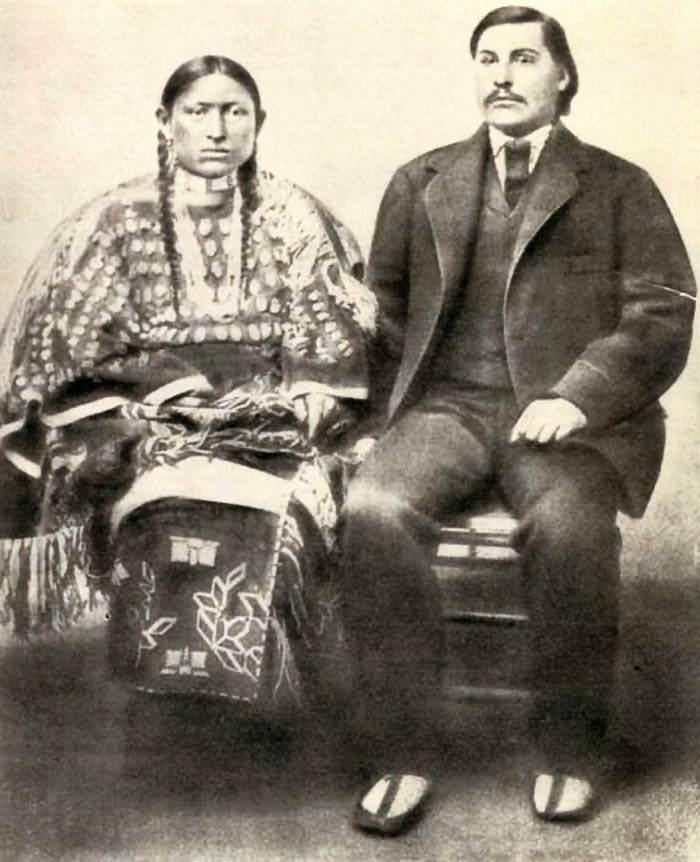

In the vast, tumultuous landscape of the American West, where cultures clashed and destinies unraveled, certain figures emerge as unique conduits of understanding. Among them, few stand as poignantly and pivotally as George Bent. Born of two worlds – the Cheyenne and the Anglo-American – his life was a crucible of identity, loyalty, and survival, ultimately transforming him into an indispensable voice for a people on the brink of erasure.

Bent’s story is not merely a footnote in the saga of westward expansion; it is a primary, intimate account of the Plains Wars, the profound tragedy of cultural collision, and the painstaking effort to preserve a vanishing way of life. From a privileged upbringing in the shadow of a frontier trading post to fighting alongside his Cheyenne kin against the encroaching tide of white settlement, and finally, to becoming the most prolific chronicler of Cheyenne history, Bent’s journey is a testament to resilience, adaptation, and an unwavering commitment to truth.

A Foot in Two Worlds: Early Life and Education

George Bent was born in 1843 at Bent’s Fort, a formidable adobe trading post on the Santa Fe Trail in what is now southeastern Colorado. His father was William Bent, a shrewd and influential American fur trader who had established a vast commercial empire. His mother was Owl Woman, a daughter of the influential Cheyenne chief White Thunder. This lineage placed young George at the very nexus of two distinct, yet increasingly interdependent, civilizations.

His early years were a fascinating blend of cultures. He learned English from his father and the traders, and Cheyenne from his mother, her sisters (including Yellow Woman, who became his stepmother after Owl Woman’s death), and his numerous relatives in the nearby Cheyenne camps. He rode horses, hunted buffalo, and absorbed the rich oral traditions and spiritual beliefs of the Cheyenne. Yet, his father, recognizing the inevitable march of American society, chose to send George and his younger brother, Charles, East for an education.

At the age of ten, George was sent to Westport, Missouri, and later to St. Louis, where he attended a private academy. For nearly a decade, he lived as a young white gentleman, learning Latin, mathematics, and the refinements of American society. He wore tailored suits, ate with forks, and read books. This period was formative, equipping him with literacy and a keen understanding of the white world’s motivations and methods. However, it also created a deep internal schism. He was a Cheyenne by blood and upbringing, yet schooled to be an American. This duality, this straddling of an ever-widening cultural chasm, would define his entire adult life.

The Crucible of Conflict: Return to the Plains and the Sand Creek Massacre

In 1863, at the age of 20, George Bent returned to the West, drawn by the familiar landscapes and the pull of his Cheyenne family. He arrived at a volatile moment. Tensions between Native Americans and white settlers, fueled by gold rushes, land hunger, and broken treaties, were escalating rapidly. The vast buffalo herds, the very lifeblood of the Plains tribes, were diminishing, and the U.S. Army’s presence was growing.

Bent found his Cheyenne people in a desperate struggle for survival. The promises of peace and protection offered by the U.S. government were proving hollow. He rejoined his mother’s people, immersing himself fully in their way of life, even participating in raids against wagon trains and military outposts – acts he would later rationalize as necessary for survival in a war initiated by the whites.

The defining, horrifying turning point in his life, and indeed for the Southern Cheyenne, came on November 29, 1864: the Sand Creek Massacre. Colonel John Chivington’s Colorado Volunteers, under orders to "kill and scalp all, big and little," attacked a peaceful camp of Cheyenne and Arapaho, flying an American flag and a white flag of truce, near Fort Lyon. Black Kettle, a prominent Cheyenne chief, had brought his people to this site under the impression they were under military protection.

George Bent was there. He witnessed the unprovoked slaughter firsthand, narrowly escaping with his life. He saw women, children, and the elderly butchered, mutilated, and scalped. The brutality of Sand Creek forever seared itself into his memory and irrevocably solidified his allegiance. It shattered any remaining illusions he might have held about the benevolence of the white world. From that day forward, his loyalty lay unequivocally with the Cheyenne.

From Warrior to Interpreter: A Unique Bridge

In the aftermath of Sand Creek, Bent fought fiercely alongside his people, participating in retaliatory raids and the desperate battles that characterized the ensuing Plains Wars. He was a skilled warrior, intimately familiar with both Cheyenne tactics and the vulnerabilities of the white soldiers. He rode with legendary Cheyenne figures like Roman Nose and witnessed the full spectrum of their struggle.

His active participation in the war, however, eventually led to his capture by U.S. troops in 1865. His identity as William Bent’s son likely saved him from execution. Instead, he was pressed into service as an interpreter, a role for which his bilingualism and bicultural background made him uniquely qualified.

This marked another profound shift in his life. While still deeply connected to the Cheyenne, he began to serve as a crucial intermediary between them and the U.S. government. He worked at various agencies, facilitating communication during treaty negotiations, rationing, and the painful transition to reservation life. He was a voice for his people, translating not just words, but cultural nuances, grievances, and hopes. His understanding of both sides allowed him to navigate the treacherous diplomatic landscape, often advocating for fair treatment and understanding, even as he witnessed the continued erosion of Cheyenne sovereignty.

The Historian’s Pen: Preserving a Vanishing World

It was in this capacity as an interpreter and cultural bridge that George Bent found his most enduring and significant purpose: that of a historian and ethnographer. Recognizing the immense knowledge he possessed, and perhaps feeling an urgent need to document a way of life that was rapidly disappearing, Bent began corresponding extensively with white scholars and researchers.

His most significant collaborations were with George Bird Grinnell, an ethnographer and naturalist who spent decades studying the Plains tribes, and George E. Hyde, an independent historian who specialized in Native American history. From the early 1900s until his death in 1918, Bent wrote thousands of letters to Grinnell and Hyde, meticulously detailing every aspect of Cheyenne life, culture, and history.

These letters, often written in his own hand, were a treasure trove of information. Bent recounted his personal experiences in the wars, the names and deeds of Cheyenne chiefs and warriors, the intricacies of their social structure, religious ceremonies, hunting practices, and daily life. He provided firsthand accounts of battles, raids, and massacres, offering an invaluable counter-narrative to the often biased or incomplete official U.S. military reports.

"My people suffered greatly," Bent wrote in one letter to Hyde, reflecting on the injustices. "They were driven from their lands, their buffalo killed, and their way of life destroyed." His accounts were not merely factual; they were imbued with the emotion, perspective, and cultural context that only an insider could provide. He corrected misconceptions, filled in gaps in existing knowledge, and brought to life the voices of those who had been silenced.

Bent’s contributions were revolutionary. At a time when much of Native American history was being written by outsiders, often with prejudice or a lack of understanding, Bent provided an authentic, internal perspective. He served as the memory of his people, translating their oral traditions, their victories, and their immense losses into a written record accessible to the wider world. His work with Grinnell formed the basis for Grinnell’s seminal book, "The Cheyenne Indians: Their History and Ways of Life," and his letters to Hyde were eventually published as "Life of George Bent: Written from His Letters."

A Lasting Legacy

George Bent passed away in 1918, a survivor of the great influenza pandemic. He lived long enough to witness the profound transformation of the American West and the confinement of his people to reservations. Yet, he left behind an unparalleled legacy.

His letters and narratives are not just historical documents; they are a profound act of cultural preservation. They offer an irreplaceable window into the Cheyenne world before and during the cataclysmic changes of the 19th century. They serve as a powerful testament to the resilience, intelligence, and humanity of a people often dehumanized in historical accounts.

George Bent’s life was a complex tapestry woven with threads of conflict, loyalty, and a deep yearning for understanding. He was the product of two worlds, and in bridging them, he ensured that the voice of the Cheyenne, a voice of courage, suffering, and enduring spirit, would resonate through the generations, long after the thunder of the buffalo and the clash of nations had faded into history. He stands as a reminder that true history is often found in the nuanced narratives of those who lived on the edges, caught between opposing forces, yet chose to illuminate the truth.