The Pathfinder and the Unwritten Map: Forging America’s Western Legends

America’s vast, untamed wilderness once stretched like an unwritten map, a canvas for myth and legend. Before the highways crisscrossed its plains and mountains, before the cities rose from its deserts, the American West was a realm of the unknown, a formidable frontier that beckoned with the promise of destiny and the peril of the untrodden. It was here, amidst the towering peaks and endless sagebrush, that real-life exploits began to fuse with national aspirations, giving birth to enduring legends. And few figures embodied this alchemical process more profoundly than John C. Frémont, "The Pathfinder," whose audacious expeditions didn’t just chart territories but carved a path through the American imagination.

The mid-19th century was a crucible of national identity. The young republic, brimming with an almost spiritual belief in its westward expansion – a concept famously dubbed "Manifest Destiny" by journalist John L. O’Sullivan in 1845 – looked longingly at the lands beyond the Mississippi. These were lands of rumor and half-truths, inhabited by indigenous nations, Spanish colonists, and a handful of hardy fur trappers. The need for accurate information was paramount: for settlers dreaming of new lives, for merchants seeking trade routes, and for a government eyeing strategic advantage. This was the stage upon which Frémont, a young, ambitious military engineer and topographer, would stride, transforming himself from a meticulous mapmaker into a figure synonymous with the conquering of the American wilderness.

Born in 1813, the illegitimate son of a French émigré and a Virginian socialite, Frémont carried a certain restless ambition. His career took a pivotal turn when he married Jessie Benton, the intelligent and influential daughter of Senator Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri, a powerful advocate for western expansion. Jessie, a formidable intellect in her own right, would prove instrumental not only in shaping Frémont’s political fortunes but also in crafting his public image, transforming dry scientific reports into thrilling narratives of adventure that captivated a nation hungry for heroes.

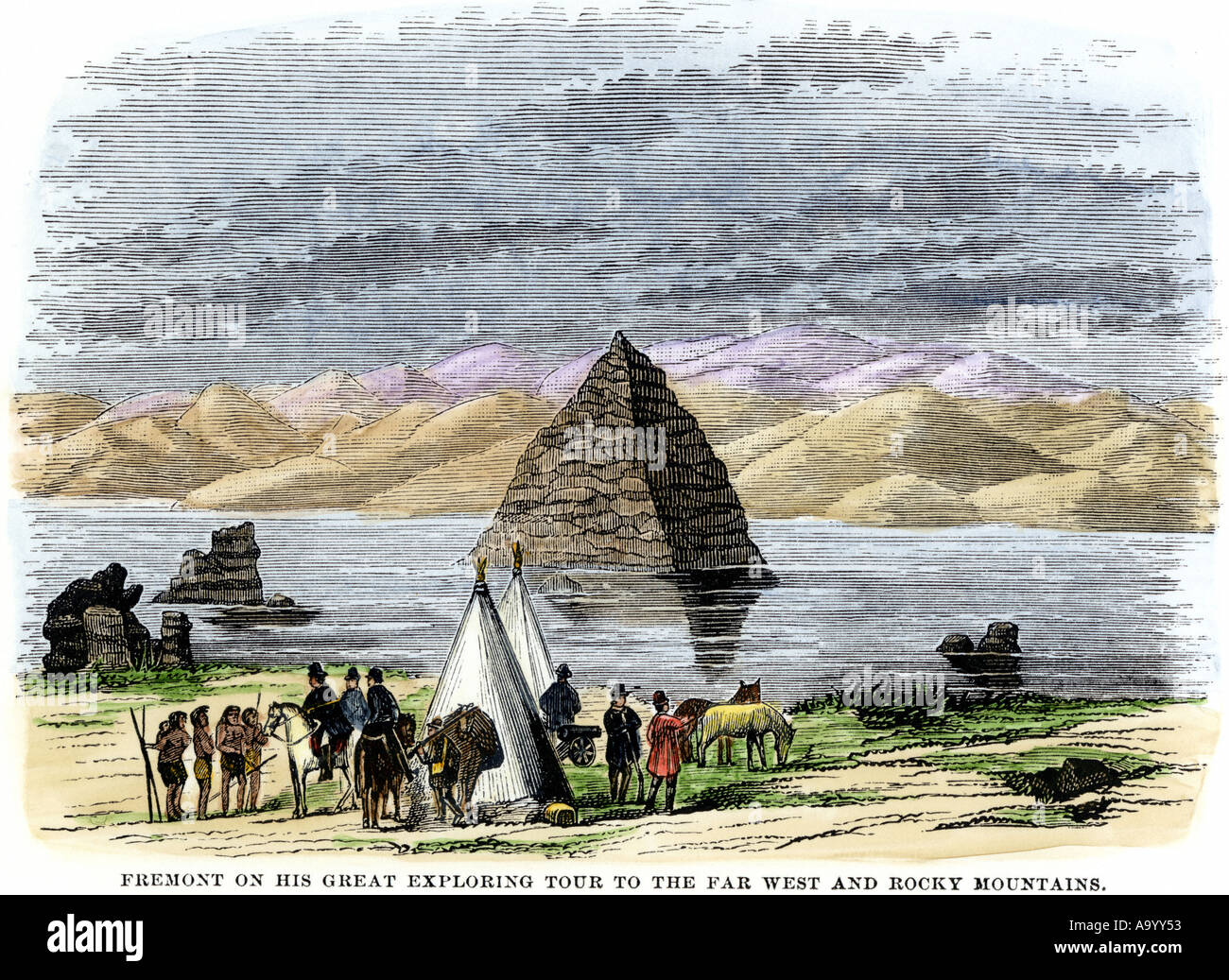

Frémont’s expeditions began in earnest in the early 1840s, a period marked by both scientific curiosity and a burgeoning sense of national destiny. His first major assignment, in 1842, was to survey the Oregon Trail region as far as South Pass in the Rocky Mountains. This wasn’t merely a cartographic exercise; it was a reconnaissance mission to assess the feasibility of westward migration. With a small, well-equipped party that included the legendary mountain man Kit Carson as his chief guide, Frémont meticulously documented the terrain, flora, and fauna. His reports, initially intended for military and scientific circles, were made accessible and engaging through Jessie’s skillful editing and writing, turning them into bestsellers that fueled the public’s imagination and drew thousands to follow the path he had surveyed.

The success of the first expedition paved the way for a far more ambitious undertaking: the grand survey of 1843-1844. This journey pushed Frémont’s party deep into uncharted territories, from the Great Basin, which he famously characterized as a vast, arid expanse "with no outlet to the sea," to the towering peaks of the Sierra Nevada. It was during this expedition that Frémont and his men endured incredible hardships, battling blizzards, starvation, and the sheer unforgiving nature of the landscape. Their dramatic winter crossing of the Sierra Nevada, an audacious feat that nearly cost them their lives, became a cornerstone of the Frémont legend. Kit Carson, whose resourcefulness and knowledge of the wilderness were repeatedly put to the test, emerged as a legendary figure in his own right, a stoic embodiment of frontier grit.

Frémont’s reports from these expeditions were revolutionary. They were not just maps but comprehensive scientific documents, detailing geology, botany, zoology, and meteorology. He carried chronometers and sextants, meticulously recording latitudes and longitudes, elevating western exploration from mere adventurism to systematic scientific endeavor. His maps, particularly the monumental 1845 map titled "Map of an Exploring Expedition to the Rocky Mountains in the Year 1842 and to Oregon and North California in the Years 1843-44," were the first truly accurate depictions of large swathes of the American West. They were essential tools for the thousands of emigrants who would soon follow in his footsteps, demystifying the vast unknown and making the impossible seem achievable. As one contemporary observer noted, Frémont "had conquered the first great enemy of the emigrant—ignorance."

The third expedition, launched in 1845, took on a distinctly political hue. As tensions escalated between the United States and Mexico over California, Frémont found himself at the nexus of exploration, military strategy, and burgeoning international conflict. His presence in California coincided with the Bear Flag Revolt, an uprising by American settlers against Mexican rule, which Frémont, with his armed party, actively supported. This controversial involvement, which blurred the lines between scientific exploration and military intervention, ultimately led to his participation in the Mexican-American War and later, a dramatic court-martial where he was found guilty of mutiny and disobedience. Though President Polk commuted his sentence, Frémont resigned from the army, his military career marred by the incident.

Despite the controversies that would dog his later life—including disastrous private expeditions, financial ruin, and a failed presidential bid as the first Republican candidate in 1856—Frémont’s legacy as "The Pathfinder" endured. He had, quite literally, put the West on the map. He had navigated its rivers, scaled its mountains, and described its deserts, providing the crucial intelligence that fueled the westward movement. His reports, ghostwritten and polished by Jessie, were more than scientific documents; they were adventure stories that ignited the American imagination, painting vivid pictures of a wild, magnificent land ripe for conquest and settlement.

The legends of America are not solely about mythical figures like Paul Bunyan or Johnny Appleseed; they are also deeply rooted in the extraordinary, often larger-than-life, exploits of real men and women who pushed the boundaries of the known world. John C. Frémont stands as a prime example of such a legend-maker. He was a complex figure: part scientist, part adventurer, part politician, and part self-promoter. His expeditions were a blend of meticulous scientific inquiry and daring, sometimes reckless, ambition. He embodied the spirit of his age—a relentless drive for discovery and expansion, a belief in the inherent rightness of American destiny.

The very act of "pathfinding" is the essence of legend-making. It is the journey into the unknown, the overcoming of insurmountable odds, the return with tales and, in Frémont’s case, maps that forever alter the perception of the world. His maps were not just lines on paper; they were blueprints for a nation’s future, guiding millions towards new horizons and transforming a vast, mysterious wilderness into a tangible, achievable dream.

Today, as we traverse the paved roads and fly over the landscapes Frémont once struggled to chart on horseback, it’s easy to forget the immense courage and vision required to face such an unknown. But the legend of John C. Frémont, "The Pathfinder," reminds us that America’s story is inextricably linked to the audacious spirit of exploration, to those who dared to step into the void and, in doing so, helped to draw the lines of a nation and etch themselves into its enduring legends. His journey wasn’t just across a continent; it was into the heart of the American dream itself, forever shaping the narrative of a people destined to move west.