The Peninsula Campaign: McClellan’s Grand Design Unravels in the Crucible of Virginia

In the spring of 1862, as the American Civil War entered its second year, the Union stood at a crossroads. Despite early skirmishes and the traumatic First Battle of Bull Run, a decisive blow against the Confederacy remained elusive. The Union’s strategic objective was clear: capture Richmond, the Confederate capital, and shatter the rebellion. To achieve this, President Abraham Lincoln turned to Major General George B. McClellan, the charismatic, meticulous, and immensely popular commander of the Army of the Potomac. McClellan, often dubbed the "Young Napoleon," envisioned a grand, audacious flanking maneuver, bypassing the heavily fortified overland approaches to Richmond by launching a massive amphibious assault down the Virginia Peninsula. It was a plan of unparalleled scale and ambition, a testament to McClellan’s organizational genius, but one that would ultimately unravel into a saga of caution, missed opportunities, and the rise of a new Confederate legend.

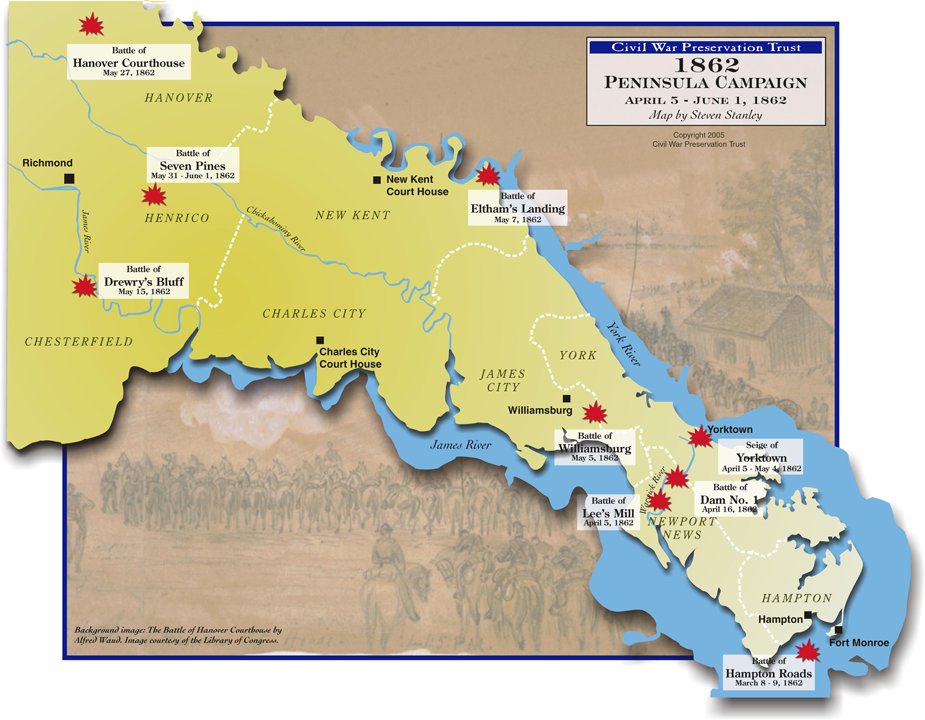

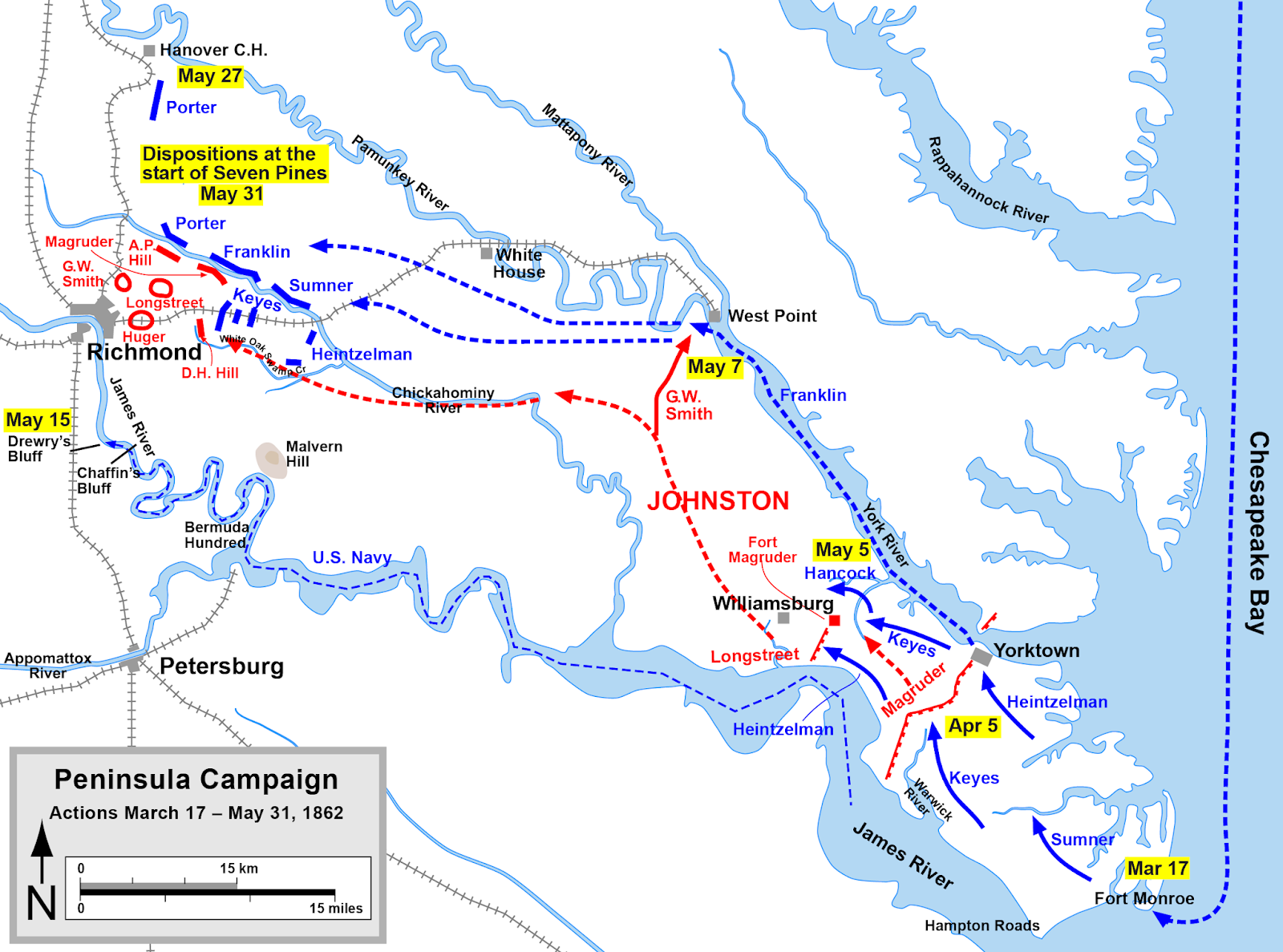

McClellan’s vision was born from a desire to avoid the bloody frontal assaults that characterized early war engagements. Instead, he proposed transporting his entire army by sea to Fort Monroe, at the tip of the Virginia Peninsula, and then advancing northwestward, up the narrow strip of land between the York and James Rivers, directly towards Richmond. This would place his forces on the Confederacy’s doorstep, theoretically catching them off guard and outflanking their main defenses. Lincoln, initially skeptical, preferring a direct overland advance to protect Washington D.C., eventually conceded to McClellan’s plan, albeit with the caveat that a substantial force remain to guard the capital.

The logistical undertaking was staggering. From March 17 to April 4, 1862, a flotilla of over 300 ships – steamers, schooners, barges – ferried more than 121,500 men, 14,592 animals, 1,224 wagons, 44 artillery batteries, and tons of supplies from Alexandria, Virginia, to Fort Monroe. It was, at the time, the largest amphibious operation in American history, a marvel of organization that showcased McClellan’s administrative prowess. The Union press hailed it as a stroke of genius, and the morale of the troops, who adored "Little Mac," soared.

However, from the outset, the campaign was plagued by McClellan’s inherent caution and an inflated perception of Confederate strength. Upon landing, the Union advance was almost immediately stalled at Yorktown. Here, a mere 13,000 Confederate defenders under Major General John B. Magruder, through clever deception tactics involving marching small units repeatedly past Union lines and mounting "Quaker guns" (logs painted black to resemble artillery), convinced McClellan that he faced an insurmountable force of 100,000 men. Rather than probe the defenses, McClellan settled into a month-long siege, calling for massive siege guns and constructing elaborate entrenchments. "I am here in front of the enemy," he wrote to his wife, "and I intend to crush him." Yet, his actions belied his words.

This delay was a critical misstep. It squandered the element of surprise, allowed Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston to withdraw his main army from Northern Virginia to reinforce Richmond, and enabled the construction of new defenses closer to the capital. Lincoln, growing increasingly frustrated, famously wired McClellan: "I think you had better break the enemy’s line at once. They are in very great fear of you." But McClellan remained unmoved. On May 3, after a month of digging and waiting, the Confederates quietly evacuated Yorktown, leaving behind only a few mines and a handful of stragglers. The grand siege had ended without a single major engagement.

The Union army cautiously pursued the retreating Confederates, clashing at Williamsburg on May 5. This battle, fought in dense woods and over formidable earthen redoubts, was a bloody, indecisive affair, but it further slowed McClellan’s advance. By late May, his vanguard was within sight of Richmond’s church steeples, tantalizingly close to the Confederate capital. The Union lines straddled the Chickahominy River, a sluggish, swampy stream prone to flooding. Two corps, IV and III, were south of the river, while the other three (II, V, VI) were to the north. This divided position, necessitated by a desire to protect supply lines and reconnoiter, exposed the Union army to a concentrated attack.

On May 31, Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston, seizing the opportunity presented by a severe thunderstorm that swelled the Chickahominy and isolated the two Union corps south of the river, launched a surprise assault known as the Battle of Seven Pines (or Fair Oaks). The fighting was fierce and confused, resulting in heavy casualties on both sides. Crucially, during the battle, Johnston was severely wounded by a shell fragment, forcing him to relinquish command. His replacement, appointed by Confederate President Jefferson Davis, would dramatically alter the course of the campaign and, indeed, the war: General Robert E. Lee.

Lee, though respected, had yet to achieve the legendary status that would define him. His early war record had been mixed, and he was sometimes derisively called "Granny Lee" for his perceived slowness. However, his appointment signaled a profound shift in Confederate strategy. Johnston had been cautious, always looking for the defensive advantage. Lee, by contrast, was aggressive, audacious, and a master of maneuver warfare. He immediately set about reorganizing the defenses of Richmond, strengthening fortifications, and renaming his command the Army of Northern Virginia – a name that would become synonymous with Confederate resilience.

McClellan, still convinced he was outnumbered, continued to demand more troops from Washington. He constantly overestimated Confederate strength, often basing his assessments on faulty intelligence and his own deep-seated belief that the Lincoln administration was deliberately undermining him. His caution was a constant source of frustration for Lincoln, who, by now, was almost pleading with his general to act. "It is indispensable to you that you strike a blow," Lincoln telegraphed McClellan on May 25. "I am sorry to have to inform you that the Richmond papers are to-day ridiculing the idea of an attack upon Richmond and declaring that you are about to retreat."

Lee, meanwhile, was anything but cautious. He understood that a prolonged siege would favor the Union’s superior resources. His plan was daring: bring "Stonewall" Jackson’s celebrated Valley Army, fresh from a brilliant campaign in the Shenandoah Valley that had tied up crucial Union reinforcements, to Richmond. With Jackson’s troops, Lee would concentrate his forces north of the Chickahominy, attack McClellan’s isolated right flank, and drive the Union army away from Richmond. This bold move, leaving only a small force to defend Richmond’s southern approaches, demonstrated Lee’s willingness to take immense risks.

The stage was set for the Seven Days Battles, a brutal series of engagements from June 25 to July 1, 1862, that would determine the fate of the campaign. The fighting began with the minor Battle of Oak Grove, a Union probing attack that achieved little. But the real action began on June 26 at Mechanicsville (Beaver Dam Creek), where Lee launched his first major assault. Though the Confederates suffered heavy casualties in frontal attacks against strong Union positions, the battle forced McClellan to reconsider his position.

The next day, June 27, witnessed the bloodiest day of the campaign at Gaines’ Mill. Lee, with Jackson’s forces finally arriving (albeit late and somewhat disorganized), launched a massive, coordinated attack against Fitz John Porter’s isolated V Corps, north of the Chickahominy. The Union troops, outnumbered and overwhelmed by repeated Confederate charges, were eventually forced to retreat across the Chickahominy. Gaines’ Mill was a decisive Confederate victory and a severe blow to Union morale. It convinced McClellan that his position north of the river was untenable and that he must "change his base" – effectively, retreat – to the relative safety of the James River, where he could receive naval support.

What followed was a harrowing week of fighting as McClellan’s army conducted a masterful fighting retreat. Battles raged at Savage’s Station (June 29), Glendale (June 30), and White Oak Swamp (June 30), as Lee relentlessly pursued the Union forces. Despite suffering heavy losses and facing fierce Confederate attacks, the Union army managed to maintain its cohesion, largely due to the superb tactical leadership of its corps commanders and the fighting prowess of its troops.

The final, climactic battle of the Seven Days occurred on July 1 at Malvern Hill. Here, McClellan’s army established a formidable defensive position atop a steep, open plateau, with artillery arrayed in tiers and supported by naval gunboats on the James River. Lee, still pressing his advantage, ordered a series of ill-advised, piecemeal frontal assaults against the impregnable Union lines. The Confederates were mown down by concentrated artillery and infantry fire, suffering thousands of casualties in a crushing defeat. "It was not war," wrote one Confederate officer, "it was murder."

Despite the tactical victory at Malvern Hill, McClellan’s confidence remained shattered. He continued his retreat to Harrison’s Landing on the James River, where his army was safe under the protection of Union gunboats. The Peninsula Campaign had failed. Richmond remained firmly in Confederate hands.

The aftermath was profound. For the Union, the campaign was a bitter disappointment. McClellan, despite his logistical brilliance and his troops’ fighting spirit, had squandered a golden opportunity. His chronic overestimation of enemy numbers, his excessive caution, and his strained relationship with Lincoln ultimately doomed his grand design. He was eventually removed from command of the Army of the Potomac later that year, though he would briefly return to lead it at Antietam.

For the Confederacy, the Peninsula Campaign was a stunning triumph. Lee had, against the odds, repulsed a far larger and better-equipped Union army from the gates of Richmond. In just over a month, he had transformed the Army of Northern Virginia into a potent offensive force and established himself as a military genius, forever altering the trajectory of the war. His audacity and strategic brilliance would inspire the Confederacy and prolong the conflict for three more years.

The Peninsula Campaign stands as a testament to the complex interplay of leadership, logistics, and psychology in warfare. It was a campaign of immense potential that ended in frustration for the Union, a grand gamble undone by a general’s caution and a new commander’s daring. It ensured that the road to Union victory would be longer, bloodier, and far more arduous than anyone in Washington had initially conceived. The crucible of Virginia had forged a new legend and redefined the struggle for the nation.