The Potlatch Ceremony: A Symphony of Giving, Power, and Resilience

In the misty, verdant landscapes of the Pacific Northwest Coast, where towering cedars meet the churning Pacific, an ancient and profound tradition has for centuries served as the heartbeat of Indigenous communities: the Potlatch ceremony. Far from a mere party, the potlatch is a complex, multi-layered social, economic, and political institution that underpins the very fabric of life for peoples like the Kwakwaka’wakw, Haida, Tlingit, Nuu-chah-nulth, and Gitxsan. It is a vibrant testament to generosity, status, and the enduring power of cultural identity, a power that even a decades-long government ban could not extinguish.

The very word "potlatch" originates from the Nuu-chah-nulth (Nootka) word "patshatl," meaning "to give" or "to distribute." This simple translation, however, barely scratches the surface of an event that can last for days, sometimes even weeks, involving elaborate feasting, ceremonial dancing, powerful oratory, and the strategic distribution and even destruction of vast quantities of wealth.

A Pillar of Pacific Northwest Societies

For thousands of years, the abundant resources of the Pacific Northwest – salmon, halibut, seals, whales, berries, and timber – fostered societies with complex social hierarchies and rich artistic traditions. Unlike many other hunter-gatherer societies, the Kwakwaka’wakw and their neighbours were not egalitarian. Status, rank, and privilege were central, inherited through kinship lines, but constantly reaffirmed and publicly validated through the potlatch.

"The potlatch was the very axis of our world," explains a Kwakwaka’wakw elder. "It was how we knew who we were, who belonged, and how our history was kept alive." Indeed, the potlatch served a multitude of critical functions:

- Legitimizing Claims: It was the primary means by which families, clans, and individuals publicly asserted or transferred rights to names, titles, territories, songs, dances, and even the right to wear certain masks or crests. A new chief’s authority, a marriage, the naming of a child, a funeral – all required a potlatch to be socially recognized and made binding.

- Economic Redistribution: While seemingly an act of lavish spending, the potlatch was a sophisticated economic system. Wealth accumulated over years – in the form of blankets (especially valuable Chilkat blankets), canoes, coppers (large, shield-shaped pieces of hammered copper, serving as high-value currency), food, and tools – was publicly distributed. This acted as a form of social insurance, ensuring that wealth circulated throughout the community, preventing extreme disparities, and creating a network of reciprocal obligations. Guests who received gifts were expected to host their own potlatches in return, often giving back more than they received, thus perpetuating the cycle of giving.

- Social Cohesion and Conflict Resolution: Potlatches fostered alliances between different groups, solidified social bonds, and could even serve as a non-violent means of resolving disputes. Rival chiefs might engage in "potlatch wars," competing to give away or destroy the most wealth, with the victor being the one who could demonstrate the greatest generosity and indifference to material possessions, thereby shaming their rival.

- Cultural Preservation: Through songs, dances, oral histories, and theatrical performances, the potlatch was a living library, transmitting ancestral knowledge, genealogies, and spiritual beliefs from one generation to the next. The intricate masks, regalia, and totem poles displayed during a potlatch were not merely art; they were powerful symbols imbued with meaning, lineage, and spiritual significance.

The Grand Spectacle

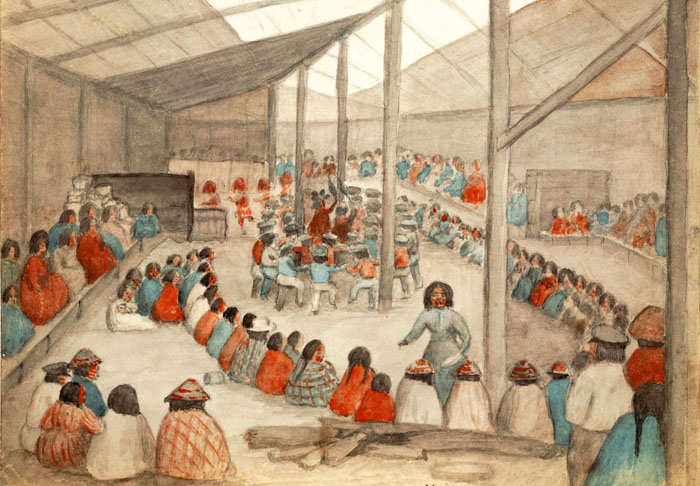

Imagine the scene: hundreds of guests arriving by canoe, their vibrant regalia shimmering against the grey sky. The air crackles with anticipation, the scent of cedar smoke mingling with the aroma of roasted salmon. Inside the longhouse, the cavernous space echoes with the rhythmic beat of drums, the haunting melodies of traditional songs, and the thunderous footsteps of dancers embodying ancestral spirits.

Preparations for a major potlatch could take years, even decades. A host family would accumulate vast quantities of goods, often through trade, fishing, hunting, and intricate networks of credit. The invitation itself was a formal affair, often delivered by a designated messenger. Guests, typically from various clans and sometimes even different nations, would travel great distances, their presence signifying their recognition of the host’s status and their willingness to bear witness to the proceedings.

During the ceremony, elaborate feasts were served, sometimes involving enormous quantities of food that showcased the host’s ability to provide. Speeches would be delivered, recounting lineages, validating claims, and sometimes challenging rivals. The highlight, however, was the gift-giving. As each guest’s name was called, they would receive a gift commensurate with their status, often with hundreds or thousands of items being distributed. In some instances, particularly among the Kwakwaka’wakw, chiefs might destroy valuable items like coppers or canoes, not out of malice, but to demonstrate their immense wealth and contempt for material possessions, thereby elevating their prestige even further.

As the renowned anthropologist Franz Boas, who extensively documented the Kwakwaka’wakw potlatch in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, observed, the ceremony was "the great motor of their social life." He understood its economic rationality, stating, "The underlying principle of the potlatch is that of a return for services rendered." It was not just about giving; it was about the complex web of reciprocal obligations and social validation it created.

The Shadow of Suppression

This powerful and deeply rooted tradition, however, became an object of severe misunderstanding and condemnation by colonial authorities and missionaries. To the Victorian mind, the potlatch appeared wasteful, irrational, and an impediment to "civilization" and the adoption of European economic models. Missionaries saw it as pagan and a hindrance to Christian conversion.

In 1884, the Canadian government, influenced by these views, amended the Indian Act to outlaw the potlatch and other Indigenous ceremonies. Section 3 of the amendment read: "Every Indian or other person who engages in or assists in celebrating the Indian festival known as the ‘Potlatch’ or in the Indian dance known as the ‘Tamanawas’ is guilty of a misdemeanor, and shall be liable to imprisonment for a term not exceeding six months, or to a fine not exceeding fifty dollars…"

This ban, which lasted for 67 years until its repeal in 1951, aimed to dismantle Indigenous social structures and assimilate Indigenous peoples into mainstream Canadian society. Its impact was devastating. Ceremonies went underground, conducted in secret, often at great risk. Artifacts associated with the potlatch, such as masks and regalia, were hidden, sold, or confiscated by authorities.

One of the most infamous incidents occurred in 1921. Despite the ban, Kwakwaka’wakw Chief Dan Cranmer hosted a massive potlatch in Alert Bay on Vancouver Island. Over 300 guests gathered for an elaborate multi-day event. When news reached authorities, police raided the ceremony, seizing hundreds of priceless artifacts and arresting 45 people. Of those, 22 were imprisoned, including Chief Cranmer, for terms ranging from two to three months. The confiscated artifacts were dispersed to museums and private collections around the world, an act of cultural vandalism that continues to resonate today.

Resistance, Resilience, and Revival

Yet, the potlatch did not die. Its spirit, deeply embedded in the identity of the people, continued to burn, albeit dimly. Elders and knowledge keepers risked imprisonment to pass on songs, dances, and the intricate protocols of the ceremony. Families continued to accumulate wealth in secret, preparing for a day when the traditions could once again flourish openly.

The repeal of the ban in 1951 was a hard-won victory, largely due to the persistent advocacy of Indigenous leaders and a gradual shift in government policy. In the decades that followed, a powerful cultural resurgence began. Communities embarked on the painstaking work of reclaiming their heritage, including the repatriation of artifacts from museums.

Today, the potlatch ceremony is experiencing a powerful revitalization. While adaptations have been made to modern contexts – some ceremonies are shorter, some gifts might be different – the core principles remain. Potlatches are once again held openly, celebrating births, marriages, graduations, and the raising of new totem poles. They are powerful affirmations of identity, a reclaiming of ancestral pride, and a means of healing from the trauma of colonial oppression.

"When we hold a potlatch now, it’s not just about giving," says a contemporary Kwakwaka’wakw artist. "It’s about survival, about strength, about showing the world that our culture is alive and well. Every drumbeat is an act of defiance, every song a prayer for the future."

The Potlatch Ceremony stands as a profound testament to the resilience of Indigenous cultures. It is more than just a historical artifact; it is a dynamic, living tradition that continues to shape communities, define identities, and embody a philosophy of generosity, reciprocity, and interconnectedness that offers valuable lessons for the contemporary world. In the echo of the drums and the rustle of the cedars, the spirit of the potlatch continues to thrive, an enduring symbol of a people who refused to be silenced.