The Potomac Under Siege: How Confederate Guns Choked Washington D.C.

WASHINGTON D.C. – In the spring of 1861, as the United States fractured and plunged into civil war, the nation’s capital, Washington D.C., found itself in an unnervingly precarious position. Nestled on the banks of the Potomac River, with the slave state of Maryland to its north and the newly seceded Virginia to its south, the city was a Union island in a sea of secessionist sentiment. While land defenses were hastily thrown up, a far more insidious threat emerged from the river itself: a Confederate blockade that would, for months, strangle the capital’s vital artery, humiliating the Union and profoundly influencing the early course of the war.

This was no distant naval engagement, but a tangible, physical chokehold just miles from the White House. The Potomac, a majestic waterway that had once been a symbol of national unity and prosperity, transformed into a dangerous frontier, bristling with Confederate artillery determined to sever Washington from the outside world.

The Capital’s Vulnerability

When Virginia seceded in April 1861, the Confederacy gained immediate control of the southern bank of the Potomac. This geographic advantage was strategic gold. The river, particularly its lower reaches, was the primary conduit for supplies, coal, and civilian traffic destined for Washington. Disrupting this flow would not only cause economic hardship but also deliver a severe psychological blow to the Union and its leadership, including a beleaguered President Abraham Lincoln.

Confederate strategists, under the overall command of General Joseph E. Johnston, recognized this vulnerability. Their plan was audacious: establish a series of shore batteries along the high bluffs of the Virginia side of the river, effectively creating an impassable gauntlet for any vessel. The objective was not necessarily to starve Washington D.C. into submission – though that was a potent fear – but to force the Union to commit resources to an arduous land route, extend their supply lines, and constantly feel the shadow of war at their very doorstep.

The First Salvos: Aquia Creek and Mathias Point

The first tangible move came in late May 1861. Confederate forces began constructing batteries at Aquia Creek, a crucial point where the Fredericksburg and Richmond Railroad met the Potomac. On May 29-30, Union gunboats, including the USS Pawnee, engaged these nascent batteries in one of the war’s earliest naval skirmishes. While the Union ships managed to inflict some damage and force a temporary Confederate retreat, they ultimately couldn’t dislodge the Confederates permanently. It was a clear sign that shore-based artillery, especially when well-positioned, posed a serious threat to wooden warships.

The Confederates learned quickly. By June, they had established another battery at Mathias Point, a more formidable position that allowed them to command a wider stretch of the river. A daring Union attempt to land and destroy this battery on June 27, 1861, resulted in a sharp repulse and the death of Commander James H. Ward, the first Union naval officer killed in the Civil War. These early encounters demonstrated the formidable challenge the Union navy faced against entrenched positions and proved to the Confederates that their strategy had merit.

An Iron Grip: Cockpit Point and Beyond

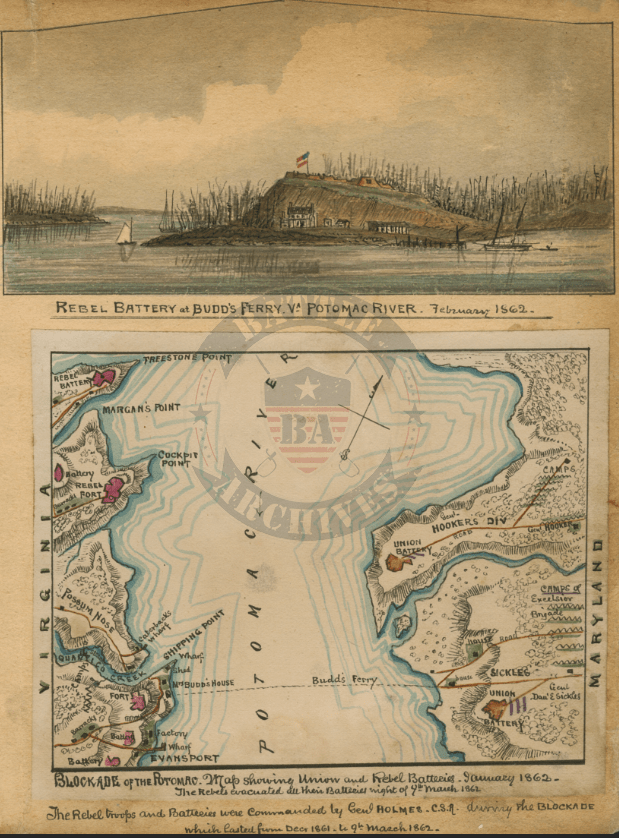

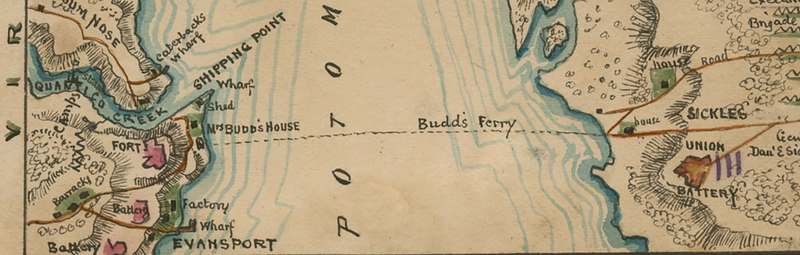

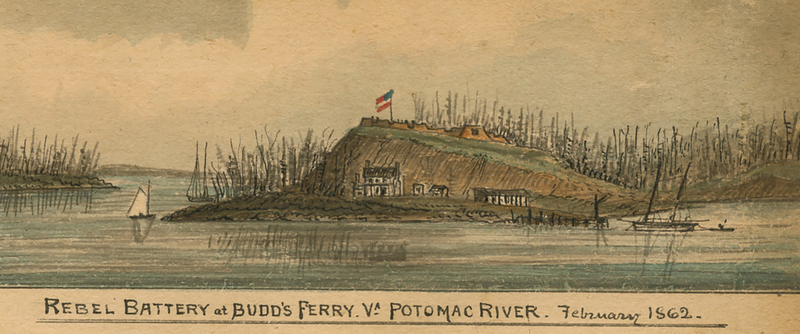

As the summer turned to autumn, the Confederate blockade tightened its grip. More batteries, increasingly sophisticated and heavily armed, appeared along the Virginia shore. Key positions included Cockpit Point, Shipping Point, Freestone Point, and Evansport. These bluffs, often towering 80 to 100 feet above the river, offered perfect vantage points for Confederate artillerymen to rain down fire on passing ships.

"From these commanding positions," noted historian John D. Milligan, "the Confederates could sweep the river with a crossfire that made passage virtually impossible for unarmed vessels and extremely hazardous for even the most heavily armed Union gunboats."

The batteries were armed with a mix of heavy Rodman smoothbore guns and, increasingly, rifled cannon which offered greater range and accuracy. By late October 1861, the blockade was fully effective. Civilian vessels, coal barges, and supply ships attempting to navigate the lower Potomac were routinely shelled and forced to turn back. Shipping to Washington D.C. ground to a halt.

Washington’s Humiliation and Lincoln’s Frustration

The impact on the capital was immediate and profound. Coal, a vital commodity for heating and industry, saw its price skyrocket. Fresh produce, once easily transported by river, became scarcer and more expensive. While Washington was not on the brink of starvation, the psychological effect was immense. The very capital of the Union was, in essence, under siege by an enemy just a few miles downriver.

Newspapers of the day fumed, demanding action. "The humiliation of having the river thus blockaded," wrote one correspondent, "within sight, almost, of the dome of the Capitol, is keenly felt." President Lincoln, known for his patience, grew increasingly agitated. He famously quipped, "Why don’t they go and drive them out?" – a question he posed repeatedly to his generals and naval commanders.

Much of Lincoln’s frustration was directed at General George B. McClellan, the celebrated commander of the Army of the Potomac. McClellan, meticulous to a fault and prone to overestimating enemy strength, was reluctant to launch a direct assault on the Confederate batteries. He believed such an attack would be costly and distract from his grander plans for a sweeping land campaign. He argued that the batteries were merely a nuisance that could be bypassed.

Naval attempts to dislodge the batteries proved equally frustrating. Union gunboats, though powerful, were vulnerable to well-placed shore batteries, especially those protected by earthworks. The low-lying trajectory of naval guns made it difficult to hit targets on high bluffs, while the Confederate guns could fire down with devastating effect. The Confederates even employed "Quaker guns" – logs painted black to resemble cannons – to further deceive Union observers about their true strength. This psychological warfare added to the Union’s hesitations.

The Winter of Discontent and Strategic Shifts

The winter of 1861-1862 saw the blockade at its peak. The Union was forced to rely entirely on railroads for supplies, a less efficient and more vulnerable alternative. The blockading of the Potomac, combined with the earlier Union defeat at First Manassas, fostered a sense of gloom and doubt in Washington. It became a potent symbol of the Confederacy’s early successes and the Union’s inability to effectively respond.

However, the tide was about to turn, not by a direct Union assault, but by a Confederate strategic realignment. As McClellan finally began his long-delayed Peninsula Campaign in March 1862, aiming to outflank the Confederate forces in northern Virginia and capture Richmond, Confederate General Johnston made a critical decision. To consolidate his forces to defend the Confederate capital, he ordered the abandonment of the Potomac River batteries.

On March 8-9, 1862, Confederate troops systematically withdrew from their positions, destroying what they could and taking their valuable heavy artillery with them. Union forces, cautiously advancing, found deserted fortifications and, in some cases, the aforementioned "Quaker guns" left as a final taunt.

The River Reopened, Lessons Learned

The relief in Washington D.C. was palpable. On March 10, the first Union steamship passed unmolested down the Potomac, signaling the end of the blockade. The river, once a symbol of vulnerability, was now open, and Washington could breathe easier.

The Potomac River blockade, though lasting less than a year, left an indelible mark on the early Civil War. For the Confederacy, it was a tactical triumph, a successful demonstration of their ability to challenge Union authority and inflict economic and psychological damage on the enemy’s very capital. It forced the Union to divert resources and rethink supply logistics.

For the Union, it was a period of profound frustration and humiliation. It highlighted the strategic importance of riverine control and the limitations of naval power against well-placed shore batteries. More importantly, it underscored the cautious, perhaps overly cautious, nature of General McClellan, contributing to Lincoln’s growing dissatisfaction with his command.

The blockade also inadvertently contributed to a technological leap. The vulnerability of wooden ships to shore batteries, coupled with the emergence of ironclads like the USS Monitor and CSS Virginia (Merrimack) in March 1862, accelerated the shift towards armored warships.

Today, as pleasure boats and commercial vessels glide peacefully along the Potomac, it’s easy to forget the dark months when Confederate guns commanded its waters, turning a vital artery into a dangerous war zone. The blockade of the Potomac River stands as a stark reminder of how close the conflict came to Washington D.C., and how even seemingly minor tactical victories could profoundly shape the narrative and strategy of the American Civil War. It was a crucial early chapter in a war that would redefine the nation, proving that even the capital itself was not immune to the harsh realities of secession and conflict.