The Powder River Bloodbath: Wyoming’s Johnson County War – A Saga of Greed, Justice, and Frontier Myth

In the spring of 1892, a chilling wind swept across the vast, untamed plains of Wyoming, carrying with it not just the last vestiges of winter, but the scent of gunpowder and the promise of bloodshed. What unfolded in the remote reaches of Johnson County was more than a mere skirmish; it was a pitched battle, a class war fought with Colt revolvers and Winchester rifles, pitting the established cattle barons against the tide of homesteaders and small ranchers. The Johnson County War, a brutal episode often romanticized in Western lore, was a stark and violent clash over land, power, and the very definition of justice on the American frontier.

To understand the ferocity of the conflict, one must first grasp the landscape of Wyoming in the late 19th century. Following the Civil War, the cattle industry boomed, transforming the open ranges of the West into a vast, lucrative pasture. Huge cattle operations, often backed by Eastern and European capital, controlled immense tracts of land, seeing the unfenced plains as their private domain. The Wyoming Stock Growers Association (WSGA), a powerful consortium of these large ranch owners, wielded immense political and economic influence, virtually dictating the laws of the territory and later the state.

Their wealth and power, however, were increasingly challenged by a new wave of settlers. Homesteaders, lured by the promise of free land under the Homestead Act, began to carve out small ranches, fencing off portions of the open range for their own cattle and crops. This influx created immediate friction. The large cattlemen viewed these newcomers as interlopers, encroaching on their traditional grazing lands and, crucially, their water sources.

The flashpoint for this simmering resentment was the issue of "rustling." The cattle barons accused the small ranchers and homesteaders of stealing their livestock. While some genuine rustling undoubtedly occurred, the definition was often blurred. Small ranchers frequently engaged in "mavericking" – branding unbranded calves found on the open range. In the eyes of the large cattlemen, any unbranded calf, regardless of where it was found, belonged to them. The WSGA, through its strict regulations and hired detectives, sought to control all branding, effectively denying small operators a legitimate way to expand their herds.

The WSGA’s grip tightened further with the "ironclad" rule, requiring members to own at least 2,000 head of cattle, effectively excluding smaller operators. They controlled the roundup, blacklisted those they suspected of rustling – often without trial or due process – and used their influence to deny them access to markets. By the early 1890s, the situation had become untenable. The large cattlemen felt their way of life was under siege, their profits dwindling, and their authority challenged. They saw the legal system as too slow, too lenient, or too easily swayed by local juries sympathetic to the homesteaders. They decided to take the law into their own hands.

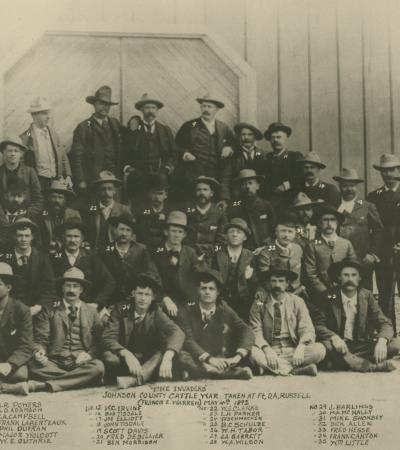

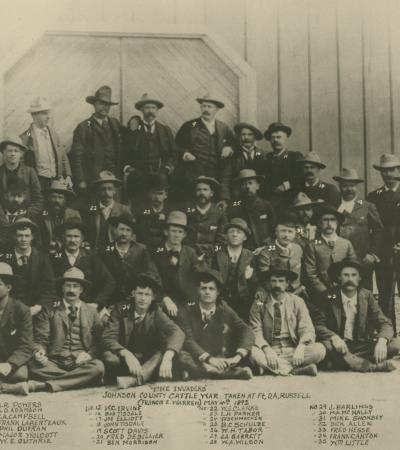

The plan was meticulously crafted and audacious in its scope. A secret contingent, later known as "The Invaders" or "The Regulators," was assembled. This force comprised around 50 well-armed men, including some of the most notorious gunfighters and former lawmen from Texas and other Western states, alongside a handful of prominent Wyoming cattlemen and their foremen. Among them was Frank Canton, a man with a checkered past as a lawman and outlaw, hired as the expedition’s field commander. Their objective: to ride north into Johnson County and eliminate a carefully selected list of individuals they deemed "rustlers" and "outlaws." The list reportedly contained over 70 names, a chilling testament to the scale of their intended purge.

On April 5, 1892, the Invaders set out from Cheyenne, traveling under the guise of a "botanical expedition." They rode covertly, often at night, making their way north towards Johnson County. Their first targets were Nate Champion and Nick Ray, two men on their death list, known for their independent spirit and their supposed involvement in mavericking.

Champion and Ray were holed up in a small, isolated cabin on the KC Ranch, south of Buffalo. The Invaders surrounded the cabin in the pre-dawn hours of April 9. A siege ensued. Nick Ray, attempting to escape, was shot and killed. Nate Champion, however, proved to be a formidable opponent. A skilled marksman and a man of immense courage, he fought back against overwhelming odds, holding off dozens of men for hours. His last stand became legendary, immortalized by a diary he kept during the siege, found later in his pocket.

In a poignant entry, Champion wrote: "Me and Nick was getting breakfast when the attack took place. I don’t know who they are but there is a hundred of them. I think. They are firing at the house now. Nick is shot and I am alone. They are trying to set the house on fire now. It’s too hot to stay in here. I wish I had a Winchester. There is a lot of them. I don’t think I will ever get out of here alive."

After a day of relentless gunfire, the Invaders resorted to desperate measures. They piled a wagon full of dry wood and brush, set it ablaze, and pushed it against the cabin. As the cabin went up in flames, Nate Champion emerged, rifle in hand, making a desperate dash for cover. He was met with a hail of bullets and fell, his body riddled with twenty-eight shots. The Invaders pinned a note on his body: "Cattle thieves, beware."

The brutal killing of Champion and Ray sent shockwaves through Johnson County. News quickly reached Buffalo, the county seat, sparking outrage and galvanizing the local population. Sheriff William "Red" Angus, a man sympathetic to the small ranchers, swiftly organized a posse of over 200 men, armed with whatever they could find, and set out to intercept the Invaders.

The Invaders, meanwhile, having accomplished their first objective, were moving towards Buffalo to continue their deadly mission. They found themselves unexpectedly cornered at the TA Ranch, near Kaycee, by Sheriff Angus’s rapidly growing posse. A tense standoff began. The posse surrounded the ranch buildings, cutting off the Invaders’ escape routes and supply lines. For two days, April 11-12, the two sides exchanged gunfire, with neither gaining a decisive advantage. The Invaders, well-armed and experienced, held their ground, but their ammunition and food supplies were dwindling.

The situation was spiraling out of control, threatening to erupt into a full-scale civil war. Sensing the impending disaster, Governor Amos W. Barber, himself a cattleman sympathetic to the WSGA, appealed to President Benjamin Harrison for federal intervention. Harrison, recognizing the gravity of the situation, ordered elements of the 6th U.S. Cavalry from Fort McKinney, under the command of Colonel J.J. Van Horn, to intervene.

The arrival of the cavalry on April 13 brought an immediate end to the siege. The sight of federal troops, heavily armed and under presidential orders, forced the Invaders to surrender. They were disarmed, arrested, and marched back to Fort McKinney, then transported to Cheyenne for trial.

The aftermath of the Johnson County War was as contentious as the conflict itself. The Invaders, including the prominent cattlemen who financed the expedition, were charged with murder and other serious offenses. However, the legal proceedings quickly became a farce. The trials were moved from Johnson County, where local sentiment overwhelmingly favored the homesteaders, to Cheyenne, where the cattle barons held sway. The WSGA, with its vast resources, hired the best legal teams and used its political influence to obstruct justice. They posted an exorbitant bail for the Invaders, which the small ranchers could never match for their own jailed members.

The prosecution, hampered by a lack of funds and political pressure, struggled to present a strong case. Witnesses were intimidated, evidence disappeared, and the trials dragged on for months, draining the state’s coffers. Eventually, in a move that epitomized the power imbalance, the charges against the Invaders were dropped due to the state’s inability to pay for the prolonged prosecution. Not a single person was convicted for the murders of Nate Champion and Nick Ray, or for the invasion itself. The outcome was a bitter pill for the small ranchers and homesteaders, reinforcing their belief that the law served only the powerful.

The Johnson County War left an indelible mark on Wyoming. While it failed to bring legal justice, it did, paradoxically, break the unchallenged dominance of the large cattle barons. Public opinion, nationally and locally, turned against the WSGA’s heavy-handed tactics. The conflict also highlighted the need for a more equitable legal system and a stronger, more impartial state government. It marked a turning point in the settlement of the West, signaling the end of the open-range era and the gradual triumph of fenced land and settled communities.

The legacy of the Johnson County War continues to resonate. It is a story of economic inequality, of the struggle between corporate power and individual rights, and of the often-brutal realities of frontier expansion. It has been mythologized in countless books, films, and songs, often simplifying the complex motivations and moral ambiguities of both sides. From Owen Wister’s classic novel The Virginian (which drew heavily on the events, though fictionalized) to the controversial 1980 film Heaven’s Gate, the war remains a potent symbol of the American West – a place where the lines between law and lawlessness, hero and villain, were often blurred, and where the fight for a piece of land could lead to a powder river running red with blood. The Johnson County War stands as a grim reminder that the taming of the American frontier was not always a story of courageous pioneers, but often a brutal struggle for survival, defined by greed, violence, and the elusive promise of justice.