The Relentless Grind: How the Appomattox Campaign Sealed the Confederacy’s Fate

The spring of 1865 was not merely a season; it was the crucible in which the American Civil War would finally be forged into an end. After four brutal years, the Confederacy, gasping for breath, found its last bastion in Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, entrenched around Petersburg, Virginia. Opposing them was Ulysses S. Grant’s colossal Army of the Potomac and Army of the James, a relentless leviathan that had choked the life out of the Southern capital, Richmond, and its vital supply hub, Petersburg, for nine agonizing months. The Appomattox Campaign, a swift, brutal, and utterly decisive ten-day chase from March 29 to April 9, was not a single climactic battle, but a series of desperate engagements, a final, grueling dance that would determine the nation’s destiny.

The stage for the campaign was set by Grant’s masterful strategy of attrition and continuous pressure. He knew Lee’s lines were stretched thin, his resources dwindling, and his men starving. Grant’s objective was not just to defeat Lee in battle, but to destroy his army utterly, rendering the Confederate cause untenable. This meant cutting off Lee’s remaining supply lines and his last escape routes to the west and south, where he might link up with Joseph E. Johnston’s forces in North Carolina.

The Hammer Blow: Five Forks and Petersburg’s Collapse

The opening salvo of the Appomattox Campaign came on March 29, 1865, as Grant extended his left flank, aiming to seize the critical South Side Railroad, Lee’s last rail link to the west. This maneuver brought Union cavalry under Maj. Gen. Philip H. Sheridan into contact with Confederate forces. The subsequent engagement at Dinkins’ Mill and White Oak Road on March 31 saw fierce fighting, with the Confederates initially pushing back elements of Maj. Gen. Gouverneur K. Warren’s V Corps. However, the true turning point was just hours away.

April 1, 1865, would prove to be a disastrous day for the Confederacy at the Battle of Five Forks. Lee had sent Maj. Gen. George Pickett’s infantry division, reinforced by cavalry, to hold this vital crossroads, often referred to as the "Southern Waterloo." Sheridan, with his formidable cavalry corps and reinforced by Warren’s V Corps, launched a crushing assault. Pickett’s men, caught largely unprepared due to a breakdown in command and communication (Pickett himself was reportedly at a shad bake miles away), were overwhelmed. The Union cavalry pinned the Confederates in front, while Warren’s infantry executed a brilliant flanking maneuver, rolling up the Confederate left. The result was a decisive Union victory, with thousands of Confederates killed, wounded, or captured. It was a crippling blow, effectively destroying Lee’s right flank and opening the door to Petersburg. Sheridan, ever the aggressive commander, was said to have ridden among his troops, shouting, "Never let a chance slip by!" The victory was absolute, but it came at a cost for Warren, whom Sheridan controversially relieved of command for what he perceived as slowness in bringing his troops into action.

News of the catastrophe at Five Forks reached Grant, who immediately ordered a general assault along the Petersburg lines for the morning of April 2. Union forces, led by Maj. Gen. Horatio Wright’s VI Corps, spearheaded the attack, smashing through the weakened Confederate defenses. The fighting was desperate and often hand-to-hand, but the Union numbers and resolve were too great. Lt. Gen. A.P. Hill, one of Lee’s most trusted corps commanders, was killed by Union soldiers while attempting to rally his troops – a poignant symbol of the unraveling Confederate cause. By afternoon, the Confederate lines had been irrevocably breached. Lee sent a telegraph to Confederate President Jefferson Davis: "I see no prospect of doing good by remaining longer than tonight in this position." The nine-month siege was over.

The Great Escape and the Relentless Pursuit

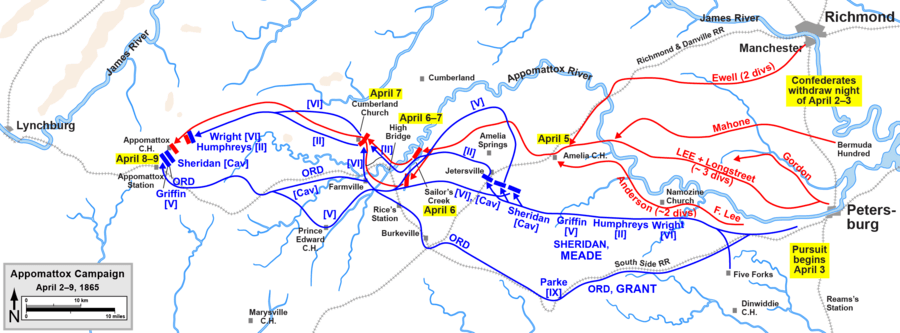

With Petersburg’s defenses shattered, Lee had no choice but to evacuate. On the night of April 2-3, under the cloak of darkness, the Army of Northern Virginia abandoned Petersburg and Richmond, which was engulfed in flames as retreating Confederates destroyed supplies and public buildings to prevent their capture. Lee’s desperate plan was to march west, gather provisions at Amelia Court House, and then turn south to link up with Johnston’s army in North Carolina. It was a gamble against impossible odds, with his exhausted, starving troops facing a determined and numerically superior foe.

The retreat quickly devolved into a nightmare. The promised rations at Amelia Court House never materialized, leaving the Confederates to forage in a desolate landscape. Meanwhile, Grant’s forces, particularly Sheridan’s cavalry and Maj. Gen. Edward O.C. Ord’s Army of the James, embarked on a relentless pursuit, mirroring Lee’s every move, constantly threatening his flanks and rear.

The chase culminated in one of the most disastrous days for the Confederacy: April 6, 1865, at the Battle of Sayler’s Creek (or Sailor’s Creek). Lee’s army had become strung out, its rearguard and two corps (Lt. Gen. Richard S. Ewell’s and Maj. Gen. Custis Lee’s command, including many naval battalion troops and government clerks) separated from the main body by swollen creeks and Union pressure. Sheridan’s cavalry, supported by elements of the VI Corps, trapped these isolated Confederate units. In a series of chaotic and brutal engagements, Union forces overwhelmed the Confederates. Ewell’s entire corps and Custis Lee’s division were captured, a staggering loss of some 7,700 men. Witnessing the surrender from a nearby hill, Robert E. Lee reportedly exclaimed, "My God! Has the army dissolved?" It was a devastating blow, depriving him of a significant portion of his remaining fighting force and shattering morale.

The retreat continued, a grueling march of starvation and despair. On April 7, skirmishes broke out at Farmville and High Bridge. At High Bridge, Confederates attempted to burn critical bridges over the Appomattox River to slow the Union pursuit, but elements of Ord’s corps arrived in time to save one of the railroad bridges, securing a path for the Federals to continue their relentless drive. Lee’s army, now a shadow of its former self, pushed on, hoping to reach Lynchburg for supplies and a temporary reprieve.

The Final Trap: Appomattox Station and Court House

The net was closing. Sheridan, ever the anticipator, recognized Lee’s likely objective. Instead of following directly, he ordered his cavalry to make a forced march, outflanking Lee and heading directly for Appomattox Station, a vital point on the South Side Railroad.

On the evening of April 8, 1865, Sheridan’s cavalry achieved its objective, reaching Appomattox Station just ahead of Lee’s main body. They swiftly captured three Confederate supply trains laden with food, denying Lee’s starving army its last hope for provisions. More critically, Sheridan deployed his troopers across the Lynchburg road, blocking Lee’s escape. Overnight, Ord’s infantry, having marched over 30 miles in less than 24 hours, arrived to reinforce Sheridan, forming an impenetrable barrier.

Lee was now trapped. His intelligence, tragically flawed, reported only cavalry ahead. He ordered a final attempt to break through on the morning of April 9, 1865, at Appomattox Court House. Maj. Gen. John B. Gordon’s corps, supported by cavalry, launched a desperate attack, initially pushing back the Union cavalry screen. However, as Gordon’s men crested the ridge, they were met not by more cavalry, but by the solid lines of Ord’s infantry corps, deployed in battle formation. The sight was unmistakable: the Union army was in force, directly in his path.

Gordon famously sent word to Lee: "Tell General Lee I have fought my corps to a frazzle, and I fear I can do nothing unless I am heavily supported by Longstreet’s corps." But Longstreet’s corps was too far behind, fighting off Union pursuers. Lee, facing the inevitable, uttered the fateful words: "There is nothing left for me to do but to go and see General Grant, and I would rather die a thousand deaths."

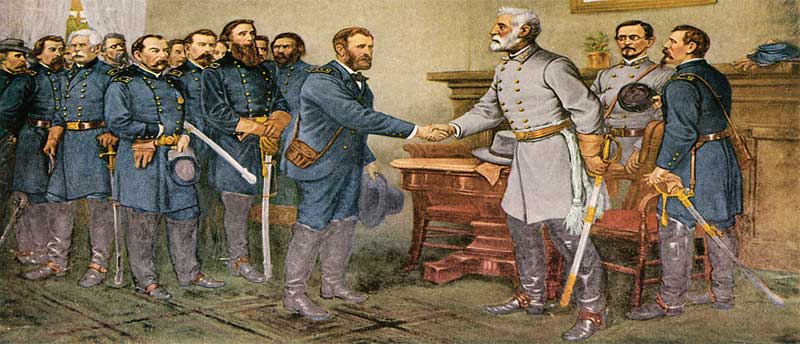

The Surrender

A white flag appeared on the Confederate lines. The fighting ceased. Later that day, in the parlor of Wilmer McLean’s house in Appomattox Court House, the two titans of the Civil War met. Grant, dressed simply, and Lee, impeccably uniformed, negotiated the terms of surrender. Grant’s terms were magnanimous: Confederate soldiers would be paroled, allowed to return home, and crucially, permitted to keep their horses and mules for spring planting. Officers could retain their sidearms. No one would be prosecuted for treason. This act of grace set a precedent for future surrenders and laid an important foundation for national reconciliation.

The Appomattox Campaign was a grim, final dance, a testament to the relentless pressure applied by Grant and the desperate, heroic resistance of Lee’s depleted army. It was not a single, glorious battle, but a grueling series of skirmishes, forced marches, and strategic maneuvers that culminated in the absolute destruction of the Confederacy’s most formidable fighting force. The campaign, which began with a tactical breakthrough at Five Forks, ended with a strategic encirclement at Appomattox, effectively bringing the bloody American Civil War to its long-awaited, poignant, and ultimately unifying conclusion.