The Roar Before the Storm: Rosebud Creek and the Battle That Changed History

The Montana sun, typically a harbinger of warmth and life, beat down with a different kind of intensity on June 17, 1876. Beneath its indifferent gaze, along the broken terrain of Rosebud Creek, a pivotal confrontation unfolded – a battle often overshadowed by the cataclysmic events that followed just eight days later, yet one that irrevocably shaped the course of the Great Sioux War. This was the Battle of the Rosebud, or as the Lakota knew it, "The Battle Where the Girl Saved Her Brother," a tactical draw that proved a strategic victory for the Plains Indians and a harbinger of the doom awaiting George Armstrong Custer.

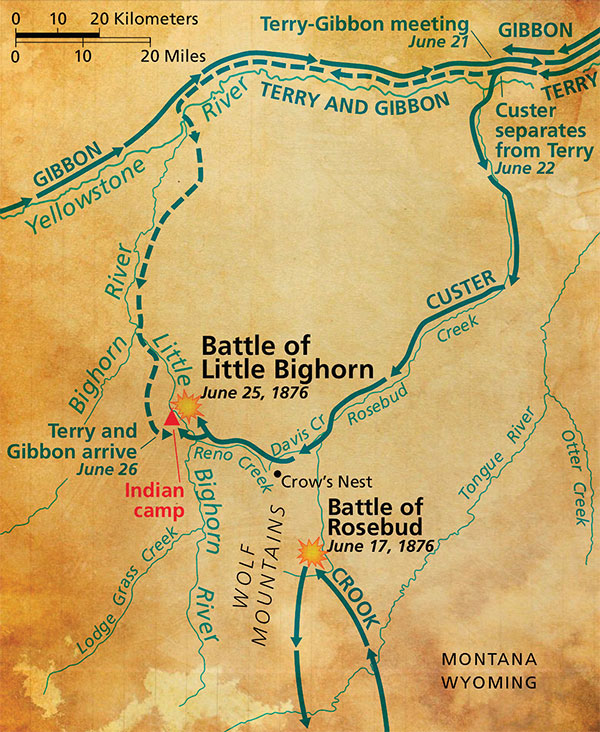

To understand Rosebud, one must first grasp the broader context of 1876. The United States government, driven by the lure of gold in the sacred Black Hills and a desire to confine the "wild" tribes to reservations, launched a massive campaign to force the Lakota Sioux and Northern Cheyenne onto their designated lands. Three columns were dispatched: Colonel John Gibbon from the west, General Alfred Terry (with Custer’s 7th Cavalry) from the east, and General George Crook from the south. Their mission was clear: converge and crush the "hostiles" who defied the reservation system.

General George Crook, known as "The Gray Fox" for his cunning and experience in Indian warfare, commanded the largest of these forces. His Big Horn & Yellowstone Expedition comprised some 1,000 cavalrymen from the 2nd and 3rd U.S. Cavalry, 150 infantrymen from the 4th and 9th U.S. Infantry, and crucially, a contingent of approximately 260 Crow and Shoshone scouts – traditional enemies of the Sioux and Cheyenne, whose knowledge of the terrain and enemy tactics would prove invaluable, yet ultimately insufficient.

Crook’s objective was to locate and engage the main body of the non-treaty Lakota and Cheyenne, believed to be camped somewhere in the Tongue or Rosebud River valleys. He moved north from Fort Fetterman, Wyoming, with confidence, perhaps bordering on overconfidence. He had fought and defeated Indians before, and he believed his seasoned troops and superior firepower would prevail. What he underestimated, however, was the sheer number of warriors he was about to face, their unified resolve, and the tactical genius of their leader, Crazy Horse.

The Lakota and Cheyenne, far from being scattered, had gathered in an unprecedented concentration along the Little Bighorn River. They were defending their way of life, their hunting grounds, and their sacred lands. Spiritual leaders like Sitting Bull had foretold a great victory for the warriors, strengthening their resolve. Crazy Horse, the legendary Oglala Lakota war leader, along with other prominent chiefs, commanded a force estimated at between 1,500 and 2,000 warriors – a formidable fighting machine fueled by desperation and a deep understanding of their homeland.

On June 16, Crook’s column camped on the upper reaches of Rosebud Creek. That night, his Crow and Shoshone scouts, ever vigilant, warned him of a large enemy force nearby. Crook, however, despite his reputation, seemed to dismiss the urgency, failing to post adequate pickets or prepare his command for an imminent assault. He believed the main Indian village was still some distance away, and that he would initiate the attack on his terms. This miscalculation would prove nearly fatal.

The dawn of June 17 broke with an unexpected fury. Around 8:30 AM, as Crook’s troops were preparing to resume their march, the sound of war cries echoed through the ravines, followed by the thunder of hundreds of hooves. Crazy Horse and his warriors, having ridden all night, launched a surprise attack on Crook’s exposed column. The initial assault struck Crook’s Crow and Shoshone scouts, who were out ahead of the main column, buying precious moments for the U.S. soldiers to form a defensive line.

The battle immediately devolved into a chaotic, sprawling engagement across a six-mile front of broken ridges, ravines, and timbered slopes. Unlike typical Indian battles, where hit-and-run tactics predominated, the warriors at Rosebud fought with sustained ferocity, pressing their advantage. They repeatedly charged, feigned retreats to draw soldiers into ambushes, and used the terrain to their benefit, appearing and disappearing as if by magic.

Crook, taken by surprise, struggled to gain control. He attempted to use traditional cavalry tactics, ordering charges and flanking maneuvers, but the terrain and the fluid nature of the Indian attack made decisive engagement impossible. His troops were constantly under pressure, their lines stretched thin. At one point, a fierce charge by Cheyenne warriors nearly overwhelmed Captain Guy V. Henry’s battalion of the 3rd Cavalry, inflicting heavy casualties and wounding Henry himself. It was during this desperate moment that one of the most compelling stories of the battle unfolded.

Amidst the swirling dust and the chaos of battle, a young Cheyenne woman named Buffalo Calf Road Woman (also known as Brave Woman) witnessed her brother, Chief Comes in Sight, dismounted and surrounded by U.S. soldiers. Without hesitation, she rode into the thick of the fighting, snatched her brother from certain death, and carried him to safety. Her act of unparalleled bravery reportedly galvanized the Cheyenne warriors, inspiring them to renew their assault with even greater vigor. The Cheyenne would later recount that her courage was a key factor in the warriors’ sustained effort that day. Indeed, it is said that it was this battle, and this specific act, that earned her the honor of striking the blow that knocked Custer from his horse at Little Bighorn a week later, though this remains a point of historical debate.

For six grueling hours, the battle raged. Crook’s Crow and Shoshone scouts fought with exceptional courage and skill, often engaging their traditional enemies hand-to-hand and preventing the complete collapse of the U.S. lines. They understood the Indian tactics better than Crook’s regular army officers and warned of impending ambushes. "They came in a solid body," recounted White Man Runs Him, a Crow scout, "they were not fooling that day."

Despite several attempts by Crook to envelop the Indian forces, Crazy Horse masterfully controlled the flow of the battle, preventing the Americans from concentrating their fire or gaining a decisive advantage. He understood that his goal was not necessarily to annihilate Crook’s force, but to stop its advance and deny it the ability to link up with the other U.S. columns.

By early afternoon, with his troops exhausted, low on ammunition, and having sustained significant casualties (10 killed, 21 wounded, according to Crook’s official report, though Indian accounts suggest higher numbers), Crook ordered a withdrawal. He declared the battle a victory, claiming to have driven the Indians from the field. However, his actions spoke louder than his words. Instead of continuing his march north to link up with Terry and Custer, Crook retreated south to his supply base on Goose Creek, remaining there for weeks to "refit" and await reinforcements.

This retreat was, for all intents and purposes, a strategic defeat for the U.S. Army. Crook had failed to achieve his objective: to find and crush the main body of the hostile Indians. More importantly, his withdrawal meant that one of the three prongs of the U.S. offensive was now out of play. The very warriors who had faced Crook at Rosebud, their morale bolstered by their success in halting "The Gray Fox," were now free to return to their massive encampment on the Little Bighorn.

Eight days later, on June 25, 1876, General George Armstrong Custer, unaware of Crook’s setback and underestimating the strength of the Indian forces, would ride into the valley of the Little Bighorn. He expected to find a scattered and fleeing enemy. Instead, he found the full, unified might of the Lakota and Cheyenne, fresh from their victory at Rosebud, ready and eager to fight. The Battle of the Little Bighorn, "Custer’s Last Stand," would become one of the most famous and tragic chapters in American history, and it was the direct, undeniable consequence of the Battle of the Rosebud.

The Battle of Rosebud, while not as widely recognized as Little Bighorn, stands as a crucial turning point. It showcased the remarkable military prowess and unified resistance of the Plains Indians under Crazy Horse’s leadership. It demonstrated the folly of underestimating an enemy fighting for its survival. And most importantly, it bought the Lakota and Cheyenne the precious time and strategic freedom that would allow them to deliver a devastating blow to the U.S. Army, forever etching their defiance into the annals of history. The roar at Rosebud was not just a battle cry; it was the prelude to a storm that would engulf Custer and his men, forever changing the narrative of the American West.