The Roaring Rivers: An Epic Saga of Rushing White Pine

Imagine a river, not of water, but of timber. A churning, thundering mass of logs, millions of board feet strong, surging downstream with an unstoppable force, guided by a handful of daring men who danced on the shifting, treacherous surface. This was the dramatic reality of "rushing white pine," an iconic, perilous, and profoundly influential chapter in North American history, particularly across New England, the Great Lakes region, and parts of Canada. More than just a method of transportation, it was an industry, a culture, and a way of life that shaped landscapes, economies, and the very spirit of a young nation.

The story begins deep within the vast, pristine forests of the 19th century, where the Eastern White Pine (Pinus strobus) reigned supreme. Towering to over 200 feet, with straight, clear trunks often four to six feet in diameter, these magnificent trees were the monarchs of the woods. Their timber was light, strong, and easily worked, making them ideal for everything from ship masts that propelled the world’s navies to the framing of burgeoning towns and cities. The demand was insatiable, fueled by rapid industrialization and westward expansion. But the challenge was immense: how to get these colossal logs from remote, often inaccessible forest stands to the burgeoning sawmills often located hundreds of miles downstream?

The answer lay in the natural arteries of the land: the rivers. For generations, indigenous peoples had used these waterways, and early settlers quickly adapted their methods. But it was the industrial scale of the 19th century that transformed the simple act of floating a log into the organized, epic undertaking known as the log drive, or "rushing white pine."

The Winter Harvest: Birth of a Drive

The process began long before the first log hit the water, in the bitter depths of winter. As soon as the ground froze and snow blanketed the forests, logging camps sprang to life. Hundreds of men, often French-Canadian, Irish, or Scandinavian immigrants, toiled from dawn till dusk. With axes and crosscut saws, they felled the giants, limbed them, and cut them into manageable lengths – typically 12 to 20 feet. These logs were then hauled by teams of oxen or horses over iced-up sled roads to the banks of frozen rivers and streams, where they were meticulously stacked in enormous piles, sometimes dozens of feet high, awaiting the spring thaw.

"The silence of those winter woods was profound, broken only by the ring of steel on wood and the groan of straining oxen," recounted a historical account from a Maine logging museum. "But beneath that quiet industry, there was an anticipation, a knowledge that soon, those logs would awaken the river."

The Spring Thaw: The River Awakens

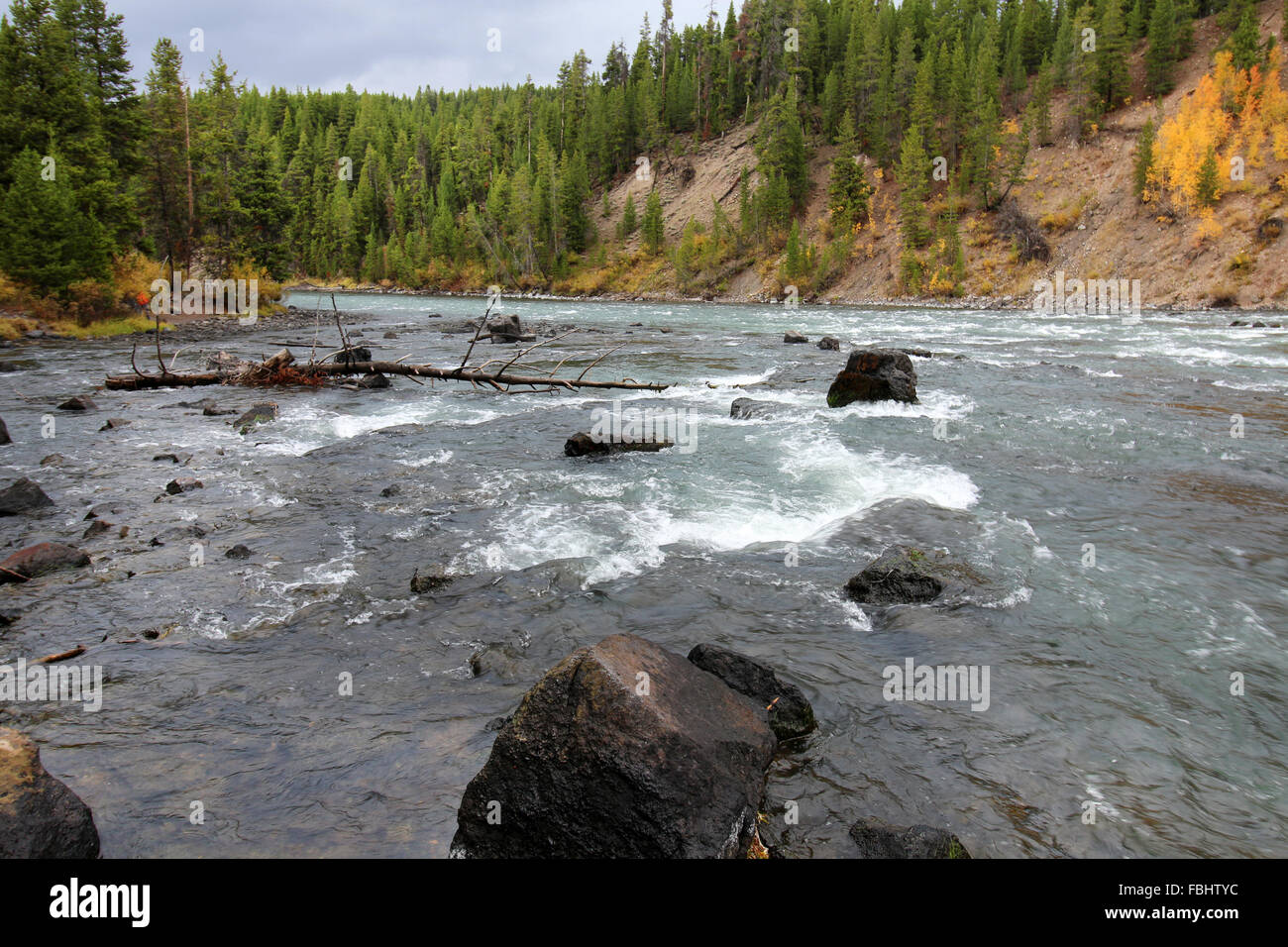

As winter’s grip loosened and the sun warmed the land, the rivers began to swell with snowmelt. This was the signal. The "drive" was about to begin. The lumberjacks, now transformed into "rivermen" or "river hogs," would break up the ice and strategically release the colossal log piles into the surging current. It was a moment of immense power and precision, as thousands upon thousands of logs, each weighing hundreds or even thousands of pounds, began their wild journey.

The rivermen were a breed apart. Dressed in heavy wool and spiked boots, they were masters of balance, agility, and courage. Their primary tools were the peavey (a cant hook with a pointed spike, invented by Joseph Peavey of Stillwater, Maine, in 1858) and the cant hook – essential for prying, rolling, and guiding logs. They lived a nomadic existence for weeks, sometimes months, following the drive downstream. Their temporary camps, known as "wanigans" (floating cook shanties), followed them, providing sustenance – often copious amounts of beans, salt pork, and bread – to fuel their arduous labor.

Dancing with Danger: The Log Jam

The greatest challenge, and the most iconic image of rushing white pine, was the log jam. Imagine millions of board feet, stretching for miles, suddenly snagging on a shallow spot, a bend in the river, or a rock formation. The logs would pile up, crisscrossing, interlocking, forming a colossal, often terrifying, natural dam. The pressure exerted by the flowing water and the weight of the logs was immense, capable of crushing anything in its path.

Clearing a jam was the ultimate test of a riverman’s nerve and skill. It was a perilous, often deadly, endeavor. Men would scramble onto the shifting, groaning mass, listening for the tell-tale creaks and groans that signaled imminent collapse. Their goal was to identify and dislodge the "key log" – the single log whose removal would unlock the entire jam.

"There’s no feeling quite like standing on a log jam, listening to it breathe, knowing that one wrong move could send you to the bottom," an old riverman was once quoted as saying. "It was a battle of wits against raw power, and the river always had the upper hand." Many lives were lost, crushed between logs, swept away by the current, or drowned in the frigid waters. Yet, the work continued, driven by the urgency of the market and the sheer determination of the men.

The Boom and the Mill

As the drive neared its destination – often a major sawmill town like Bangor, Maine; Williamsport, Pennsylvania; or Saginaw, Michigan – the logs entered a "boom." This was a series of connected logs or chains, forming a giant floating fence that corralled the timber in a specific area of the river or lake. Within the boom, logs belonging to different companies, each marked with a unique stamp, would be sorted and guided into their respective mill ponds.

The sawmills themselves were industrial marvels, roaring with the sound of steam engines and circular saws. Here, the white pine logs, after their epic journey, were finally transformed into lumber, ready to be shipped by rail or sea to distant markets. The towns that grew up around these mills boomed, fueled by the seemingly endless supply of timber and the hard labor of thousands.

Economic and Environmental Impact

The era of rushing white pine was a cornerstone of industrial growth in North America. It provided the raw material that built cities, powered factories, and fueled an economic expansion that transformed the continent. Fortunes were made, and the logging industry became a powerful force, shaping political landscapes and fostering technological innovation.

However, this prosperity came at a significant cost. The environmental impact was profound and often devastating. Vast tracts of old-growth white pine forests were clear-cut, leading to widespread deforestation and habitat destruction. The rivers themselves were dramatically altered. Dams were built to create reservoirs for regulating water flow, and chutes were constructed to bypass rapids. The sheer volume of logs scoured riverbeds, destroying aquatic habitats and altering natural ecosystems. Sedimentation from eroded hillsides and decaying bark from the logs further degraded water quality.

"The rivers that once flowed clear and pristine became arteries of commerce, but also carriers of immense ecological disruption," noted Dr. Sarah Jenkins, a historical ecologist. "The scale of the logging was so vast that it irrevocably changed the landscape of entire regions, the effects of which we are still managing today."

The Decline of an Era

By the early 20th century, the golden age of rushing white pine began to wane. Several factors contributed to its decline:

- Depletion of Forests: The seemingly endless supply of old-growth white pine was, in fact, finite. As the most accessible stands were cut, loggers had to venture further afield, making river drives less efficient.

- Technological Advancements: The expansion of railroads and the development of steam-powered logging machinery made it possible to transport logs over land more efficiently and reliably, reducing reliance on rivers. Later, the advent of powerful logging trucks further diminished the need for river drives.

- Hydroelectric Dams: The proliferation of hydroelectric dams across major rivers created impassable barriers for logs, making drives impossible on many waterways.

- Environmental Concerns: Growing awareness of the ecological damage caused by log drives and deforestation led to increased regulations and a push for more sustainable forestry practices.

The last major commercial log drive in the United States took place on the Kennebec River in Maine in 1976, marking the symbolic end of an era. The spectacle of millions of logs thundering downriver became a thing of the past, relegated to history books and folk songs.

Legacy and Remembrance

Today, the legacy of rushing white pine endures in various forms. Museums and historical societies across New England and the Great Lakes region preserve the tools, stories, and photographs of this remarkable period. Folk music, poetry, and literature continue to romanticize the arduous lives of the rivermen, celebrating their courage and skill. Rivers that once flowed brown with bark and timber now run clearer, and in many areas, reforestation efforts have slowly begun to heal the scars of intensive logging.

The saga of rushing white pine serves as a powerful reminder of humanity’s complex relationship with nature. It speaks to an era of immense resourcefulness, daring, and industrial ambition, but also to the profound environmental consequences of unchecked exploitation. It’s a tale of men who tamed wild rivers, not with brute force alone, but with an intimate knowledge of the currents, the timber, and the very spirit of the water. Their echoes can still be heard in the roar of spring runoff, a ghostly reminder of the millions of white pines that once surged downstream, building a nation, one log at a time.