The Rocky Mountain Dream: Unpacking the Ambitious Saga of the St. Louis Rocky Mountain & Pacific Company

In the annals of American railway history, many companies bore names that thundered with continental ambition – names that evoked vast stretches of land, distant oceans, and the relentless march of progress. Among these, the St. Louis Rocky Mountain & Pacific Company (SLRMP) stands out as a particularly poignant example. Incorporated in 1905, its very name conjured images of bustling Midwestern hubs, the majestic peaks of the Rockies, and the boundless promise of the Pacific coast. Yet, the reality of the SLRMP was a fascinating paradox: a relatively modest regional railroad whose grand aspirations far outstripped its physical reach, leaving behind a legacy woven into the rugged fabric of northern New Mexico.

The story of the SLRMP is a testament to the fervent railway expansion that characterized the turn of the 20th century, a period when investors and entrepreneurs alike saw immense potential in connecting burgeoning industrial centers with the raw resources of the American West. At its heart, the SLRMP was conceived not as a transcontinental giant, but as a vital artery for the rich coalfields and timberlands of the Raton Basin, straddling the New Mexico-Colorado border. Its headquarters may have been in the financial nerve center of St. Louis, but its tracks, its purpose, and its very soul were firmly rooted in the high desert and mountain passes of the Southwest.

The Genesis of an Ambition

The primary architect of the St. Louis Rocky Mountain & Pacific Company was Newman Erb, a prominent railway financier and president of the Pere Marquette Railroad. Erb, along with a syndicate of investors, recognized the untapped wealth lying dormant in northern New Mexico. The region, particularly around Raton, was known for its vast deposits of high-quality bituminous coal, a crucial fuel for the nation’s rapidly expanding industries and a commodity that could fetch handsome profits if efficiently transported. The vision was clear: build a railroad that would tap into these resources, connect them to the broader rail network, and facilitate the growth of the surrounding communities.

The company was incorporated with an authorized capital stock of $30 million – an astronomical sum for the time, reflecting the enormous scale of the undertaking and the confidence of its backers. Construction began swiftly, pushing tracks through challenging mountainous terrain. The main line, ultimately stretching approximately 106 miles, branched off the mighty Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway (AT&SF) at Raton, New Mexico. From there, it snaked its way westward through the scenic Cimarron Canyon, connecting towns like Cimarron, Ute Park, and ultimately reaching Des Moines, New Mexico, to the northeast. Branches also extended to vital coal camps and lumber operations, such as Dawson, Van Houten, and Gardiner.

The Lifeblood: Coal and Timber

To understand the SLRMP is to understand its symbiotic relationship with the coal industry. The railway was not merely a carrier; it was an integral part of the resource extraction economy. The company acquired vast tracts of land – over 500,000 acres – which were rich in coal and timber. It wasn’t enough to just transport the coal; the SLRMP also owned and operated several significant coal mines. This vertical integration was a common strategy in the era, ensuring a steady supply of freight and maximizing profits.

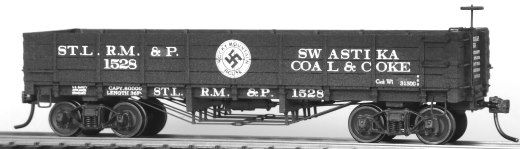

The most famous of these mining operations was undoubtedly Dawson, New Mexico. Located in a rugged canyon west of Raton, Dawson grew into one of the largest and most productive coal camps in the West. The SLRMP built a branch line directly to Dawson, hauling out millions of tons of coal and bringing in supplies, equipment, and a diverse workforce from around the world. Dawson was a bustling, self-contained community, complete with schools, hospitals, stores, and its own coke ovens, all dependent on the railway for its existence.

Similarly, the forests of the Cimarron Range provided abundant timber, another valuable commodity that found its way onto SLRMP freight cars. Sawmills sprang up along the line, turning raw logs into lumber for construction and other industries. The railway, therefore, became a powerful engine of economic development for a region that, prior to its arrival, was largely isolated and underdeveloped. It opened up new markets, created jobs, and spurred the growth of small towns that relied almost entirely on the railway and its associated industries.

The "Pacific" Paradox: A Dream Unfulfilled

The most intriguing aspect of the SLRMP’s identity lies in its name: "Rocky Mountain & Pacific." While the "Rocky Mountain" part accurately reflected its operational territory and the formidable challenges of its construction, the "Pacific" remained an ambitious, yet ultimately unfulfilled, aspiration. The railway never extended anywhere near the Pacific Ocean. Its tracks, at their furthest western reach, were still hundreds of miles from the California coast.

This "Pacific" moniker was less a geographical descriptor and more a declaration of aspiration, a common marketing strategy of the era. Many smaller railroads added grand names to attract investors, suggesting a scale and potential that might not have been immediately evident. For the St. Louis Rocky Mountain & Pacific, it hinted at a future where its regional lines might one day become part of a larger transcontinental network, or at least serve as a vital link in the chain that moved goods from the interior to the western seaboard. It spoke to the boundless optimism of a time when railway barons dreamed of connecting every corner of the nation.

Financial Realities and the Shadow of Giants

Despite its strategic importance and the wealth of resources it accessed, the SLRMP faced the relentless financial pressures inherent in railway operations. Building and maintaining track in mountainous terrain was expensive, and the ongoing need for rolling stock, locomotives, and personnel required constant capital investment. The company was profitable, but it operated in the shadow of much larger, more established railroads, particularly the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe, which effectively controlled the broader regional rail network.

The early 20th century was also a period of economic volatility. The Panic of 1907, a severe financial crisis, tested the resilience of many railway companies. While the SLRMP navigated these early storms, the long-term trends were slowly shifting against smaller, independent lines. The First World War brought a period of federal control over railroads, followed by a return to private ownership and intense competition. The rise of improved roads and the internal combustion engine also began to chip away at the railway’s monopoly on freight and passenger transport, especially for shorter hauls.

The Decline and Absorption

As the 1920s progressed, the economic landscape for regional coal-dependent railroads began to change. The demand for coal, while still strong, faced increasing competition from other energy sources like oil and natural gas. Moreover, the efficiency of mining operations improved, meaning fewer, larger mines could produce the same output, often leading to the closure of smaller, less productive sites.

For the St. Louis Rocky Mountain & Pacific Company, the writing was on the wall. Its original purpose, to serve as an independent artery for the Raton Basin’s resources, became less viable. The logical conclusion for such a line was absorption by a larger entity that could integrate its operations into a more expansive network.

In 1929, just as the nation was on the precipice of the Great Depression, the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway acquired the St. Louis Rocky Mountain & Pacific Company. It was a natural fit. The AT&SF already connected with the SLRMP at Raton and was the dominant carrier in the Southwest. The acquisition effectively brought the SLRMP’s valuable coal properties and trackage under the control of a major player, ensuring the continued, albeit integrated, operation of its lines. The SLRMP, as an independent corporate entity, ceased to exist.

A Lasting Legacy

Today, the physical remnants of the St. Louis Rocky Mountain & Pacific Company are scarce, yet its impact on northern New Mexico endures. Many of the company towns it helped create, like Dawson, are now ghost towns, their silent ruins echoing with the memories of a once-thriving industrial past. The old railbeds, though often overgrown or converted into roads, still trace the paths carved by early 20th-century ambition.

The SLRMP’s story is a microcosm of America’s industrial expansion – a tale of grand visions, the relentless pursuit of resources, the hard work of countless individuals, and the inevitable shifts of economic fortune. It reminds us that even companies with names hinting at vast, continent-spanning enterprises could have their true heart in a specific, rugged corner of the world. The St. Louis Rocky Mountain & Pacific Company, with its ambitious name and its focused purpose, remains a compelling chapter in the intricate narrative of American railroads, a testament to the dreams that built a nation, one rail tie at a time.