The Scorched Earth of Missouri: General Order 11 and the Brutality of the Border War

In the annals of American history, few chapters are as stark and unforgiving as the Civil War. Yet, within that brutal conflict, certain episodes stand out for their exceptional severity, their profound human cost, and the enduring debate they ignite. One such episode is the issuance and implementation of Missouri General Order 11, a Union directive that, in the late summer of 1863, transformed a swath of western Missouri into a desolate, "burned-out district," forever scarring the landscape and the collective memory of its inhabitants.

To understand General Order 11, one must first grasp the uniquely vicious nature of the Missouri-Kansas border. For years before the first shots of the Civil War were fired, this region was a crucible of violence, a microcosm of the national struggle over slavery. The term "Bleeding Kansas" emerged from the clashes between pro-slavery "Border Ruffians" from Missouri and abolitionist "Jayhawkers" from Kansas, each side committing atrocities against the other. When the Civil War officially began, this simmering animosity erupted into a full-blown guerrilla conflict, characterized by hit-and-run raids, ambushes, summary executions, and widespread pillaging that often transcended traditional military objectives.

The principal actors in this grim theater were not always uniformed soldiers. On the Confederate-sympathizing side, figures like William Clarke Quantrill and "Bloody Bill" Anderson led bands of bushwhackers – irregular cavalry units notorious for their brutality and their intimate knowledge of the local terrain. Their Unionist counterparts, such as James Lane and Charles R. Jennison, commanded equally ruthless Jayhawker units. This was a war fought not between armies on battlefields, but between neighbors, often with deeply personal grievances, making it exceptionally cruel and difficult to control.

The Catalyst: Lawrence’s Agony

The immediate catalyst for General Order 11 was an event of such horrifying scale that it sent shockwaves across the nation: Quantrill’s Raid on Lawrence, Kansas. In the pre-dawn hours of August 21, 1863, Quantrill and approximately 400 of his bushwhackers descended upon Lawrence, a known hotbed of abolitionist sentiment and a base for Jayhawker raids into Missouri. For four hours, the guerrillas systematically looted, burned, and murdered, killing between 150 and 200 unarmed men and boys, many of whom were dragged from their homes and shot in cold blood. The town was left in ruins, a smoldering testament to the savagery of the border war.

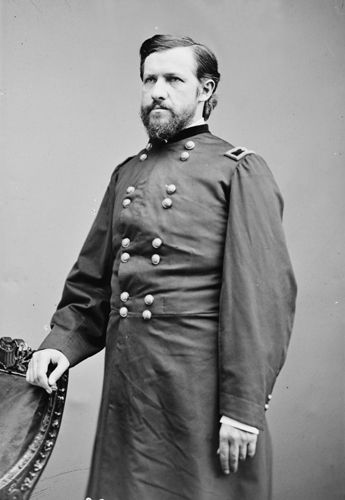

The massacre at Lawrence ignited a furious demand for retaliation and an end to the guerrilla menace. Union military authorities, who had struggled for years to suppress the bushwhackers, now felt immense pressure to act decisively. The commander of the Department of the Missouri, Major General John M. Schofield, and his subordinate, Brigadier General Thomas Ewing Jr. (brother-in-law to William Tecumseh Sherman and brother of Hugh Boyle Ewing, a prominent Missouri politician), were tasked with finding a solution.

Ewing, commanding the District of the Border from his headquarters in Kansas City, was convinced that the bushwhackers could not operate without the active or passive support of the civilian population in western Missouri. He believed that many families, while perhaps not directly participating in raids, provided food, shelter, intelligence, and a safe haven for the guerrillas. To sever this critical lifeline, Ewing concluded, radical measures were necessary.

The Order Issued: A Decree of Desolation

On August 25, 1863, just four days after the Lawrence massacre, General Order No. 11 was issued. Its language was stark, its implications devastating. The order stipulated:

- Forced Evacuation: "All persons living in Jackson, Cass, and Bates counties, Missouri, and in that part of Vernon county included in this district, are hereby ordered to remove from their places of residence within fifteen days from the date hereof." This covered thousands of square miles and tens of thousands of civilians.

- Exemptions (Limited): Residents of Independence, Pleasant Hill, and Harrisonville were exempt, provided they proved their loyalty to the Union. Those living within one mile of these towns or the military posts at Kansas City and Westport also had a conditional reprieve.

- Property Seizure/Destruction: Any grain or hay found within the affected counties after the 15-day deadline would be seized by the military or destroyed. If not removed by the owners, it was considered contraband.

- Military Enforcement: Union troops were ordered to enforce the evacuation and destroy any remaining property that could aid the guerrillas.

Ewing’s rationale, as articulated in the order, was clear: "That all persons desiring to remain in said counties must take the oath of allegiance and be known to be loyal citizens, or be so regarded by the commanding officers of the districts and posts herein mentioned." He sought to create a cordon sanitaire, a depopulated zone that would deny the guerrillas any succor.

The Implementation: A Human Catastrophe

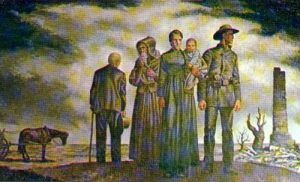

The execution of General Order 11 was a humanitarian disaster. Thousands of families, predominantly women, children, and the elderly (as most able-bodied men were either fighting or dead), were suddenly forced from their homes with little warning and less assistance. They were given a mere 15 days to gather what they could carry and leave everything else behind.

Eyewitness accounts and historical records paint a grim picture. Long lines of refugees, often on foot or in overloaded wagons, streamed out of the affected counties. They carried what meager possessions they could salvage – a few blankets, some food, cherished heirlooms. Many were forced to abandon their livestock, crops, and homes, watching as Union soldiers, often Kansas volunteers harboring deep-seated resentments from years of border warfare, systematically torched buildings, burned fields, and slaughtered animals.

"The roads were literally lined with famished women and children, begging for food," wrote one contemporary observer. Another recalled, "The air was filled with the smoke of burning homes and the lamentations of women and children." The soldiers, driven by a desire for revenge for Lawrence and years of guerrilla depredations, often showed little mercy. Homes were looted before being set ablaze, and any perceived resistance was met with force. The region quickly became known as the "Burned-Out District" or the "Burnt District."

Many refugees fled to Kansas City, Independence, or other Union-controlled towns, where they struggled to find shelter and sustenance. Others, with nowhere else to go, sought refuge with relatives or friends in more distant counties, often arriving destitute and traumatized. The order effectively rendered thousands homeless and penniless, their lives shattered by a stroke of a pen.

The Aftermath: A Scarred Landscape and Enduring Legacy

The immediate impact on the land was profound. The fertile farmlands of western Missouri, once vibrant with crops and homesteads, were transformed into a desolate wilderness. Miles upon miles of scorched earth, crumbling chimneys, and charred timbers marked where homes and farms had once stood. The economic life of the region was utterly destroyed, setting back its development by decades.

The military effectiveness of General Order 11 remains a subject of debate. While it certainly disrupted the bushwhackers’ support network and made their operations more difficult, it did not entirely eliminate them. Quantrill, Anderson, and their ilk continued to operate, albeit with greater challenges, shifting their focus to other areas or becoming even more desperate and ruthless. Some historians argue that the order, by alienating the civilian population, may have inadvertently pushed more people into supporting the guerrillas, or at least deepened their animosity towards the Union.

However, the order did achieve its stated goal of making it nearly impossible for large-scale guerrilla operations to sustain themselves in the affected counties. The flow of supplies and intelligence was severely curtailed. The psychological impact on both sides was also significant; it demonstrated the Union’s willingness to employ extreme measures to win the war, a precursor to Sherman’s later "March to the Sea."

The long-term consequences were undeniable. The animosity between Missourians and Kansans, already fierce, was cemented into a bitter, generational hatred. For decades after the war, the "Burned-Out District" remained sparsely populated, its fields slowly reclaiming the land, its scars visible. The memory of the forced exodus and the wanton destruction became a deeply ingrained part of regional identity, fostering a sense of victimhood and resentment that lingered for generations. Families who lost everything passed down their stories, ensuring that the brutality of General Order 11 would not be forgotten.

Historical Interpretation: Necessity or Atrocity?

General Order 11 stands as one of the most controversial military directives of the Civil War. Its proponents, including Ewing himself, argued that it was a harsh but necessary measure to suppress an exceptionally cruel and persistent guerrilla insurgency that was actively undermining the Union war effort. They pointed to the massacre at Lawrence as proof of the bushwhackers’ barbarity and the need for a decisive response. In a total war, they argued, the lines between combatant and civilian often blurred, and extraordinary circumstances demanded extraordinary actions.

Critics, however, condemned it as an act of egregious barbarity, a violation of the laws of war, and an unconscionable punishment of an entire civilian population for the actions of a few. They highlighted the immense suffering inflicted upon innocent women and children, many of whom were loyal Unionists caught in the crossfire. They questioned its actual effectiveness in ending the guerrilla war, suggesting it merely exacerbated the region’s misery.

Even Abraham Lincoln, though aware of the order, did not revoke it, indicating a tacit acceptance of the harsh realities of the border conflict. However, many in the Union army and in the North were uncomfortable with its severity.

Today, General Order 11 serves as a stark reminder of the dark side of warfare, particularly when it descends into irregular, brutal conflicts where civilians bear the brunt of the violence. It is a testament to the fact that even in a war fought for noble ideals, the methods employed can leave indelible stains. Monuments and historical markers in the affected counties now commemorate the tragedy, ensuring that the voices of those who suffered under Ewing’s decree are not silenced by time. The scorched earth of western Missouri remains a powerful symbol of the extreme measures taken in a war that tore a nation apart, a chapter of American history where the line between military necessity and human atrocity became dangerously, tragically thin.