The Shadow Council: How the Second Walla Walla Shaped America’s Tragic Western Legend

America’s identity is woven from a rich tapestry of legends – tales of heroic figures like Paul Bunyan and Johnny Appleseed, of pioneering spirit personified by Davy Crockett, and of monumental events like the Gold Rush or the Alamo. These stories, whether steeped in folklore or cemented in historical fact, define our collective memory and illuminate the values and aspirations that forged a nation. Yet, not all legends are born of triumph and glory. Some emerge from the crucible of conflict, from the tragic collisions of cultures and ambitions that scarred the land and its peoples. One such legend, often overlooked in the broader national narrative but profoundly significant to the American West, is the Second Walla Walla Council of 1856 in Washington Territory – a pivotal, contentious, and ultimately tragic gathering that cemented a legacy of broken promises and violent resistance.

This was no ordinary council. It was a desperate attempt to rectify a burgeoning crisis, a moment when the relentless tide of Manifest Destiny crashed headlong into the fiercely guarded sovereignty of Native American nations. It wasn’t a battle in the conventional sense of muskets and cannon fire, but a war of wills, words, and irreconcilable worldviews, whose failure ignited years of devastating conflict and etched an indelible mark on the landscape of American legend.

To understand the weight of the Second Walla Walla Council, one must first grasp the feverish climate of the mid-19th century American West. The Oregon Trail had carved a deep scar across the continent, bringing waves of settlers, missionaries, and fortune-seekers. The dream of a nation stretching "from sea to shining sea" was rapidly becoming a reality, fueled by a potent mix of economic opportunity, religious zeal, and a pervasive belief in American exceptionalism. Governor Isaac Stevens of Washington Territory, a man of relentless ambition and unshakeable conviction, was a key architect of this expansion. Tasked with securing land for new settlements and vital transportation routes, Stevens embarked on an aggressive treaty-making campaign.

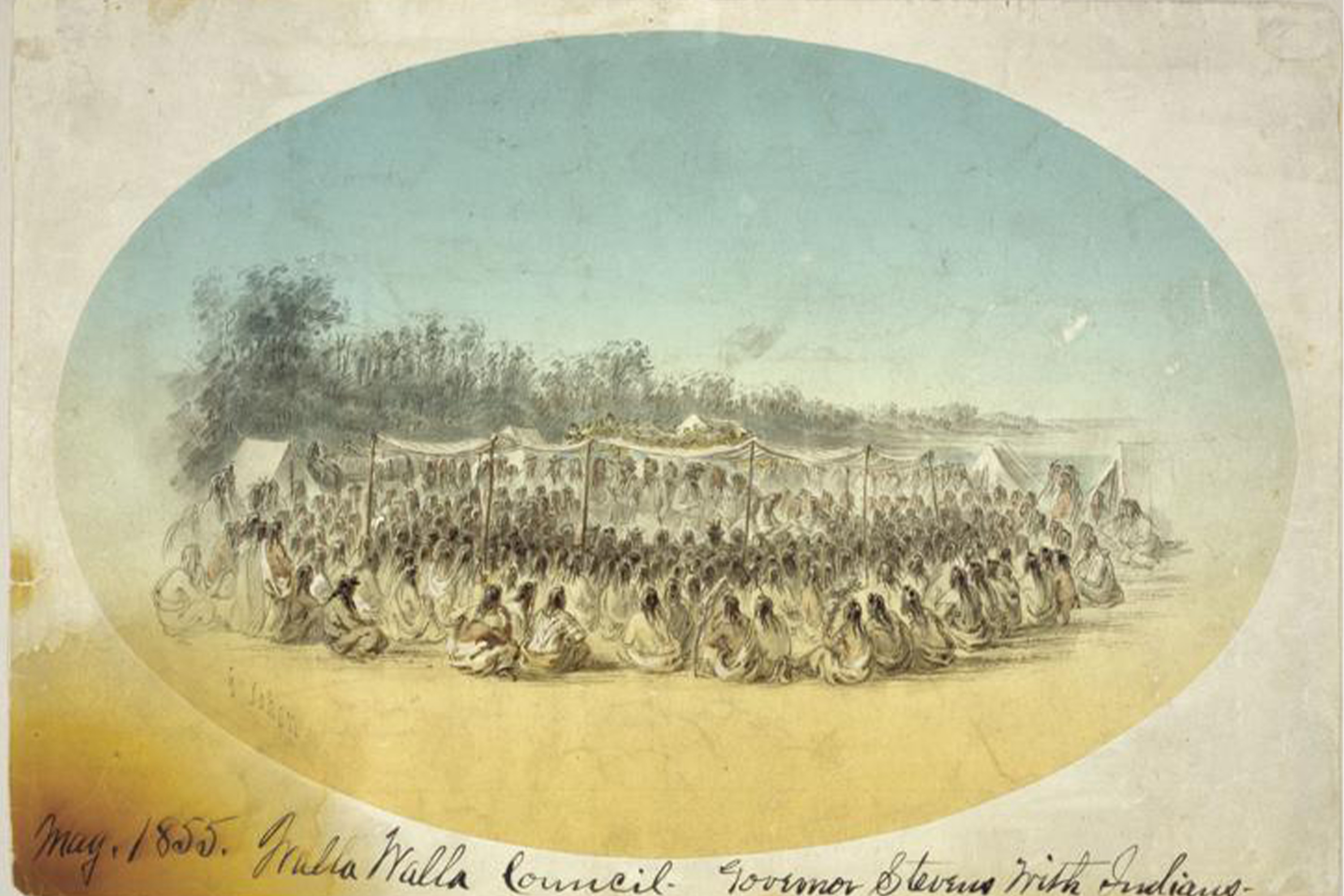

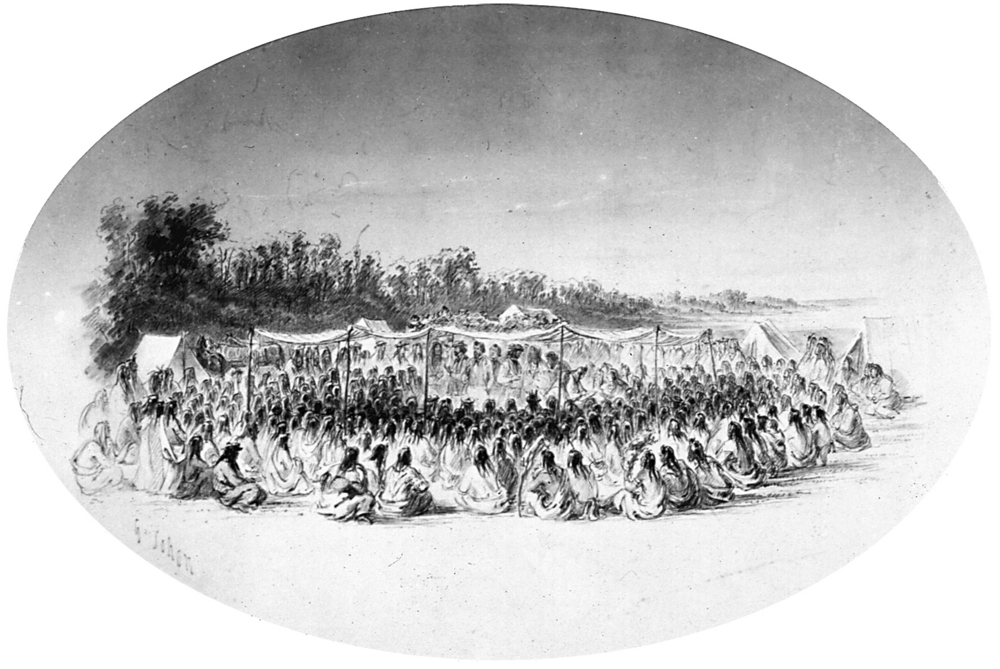

The First Walla Walla Council in May and June of 1855 was Stevens’s initial triumph. There, he had gathered thousands of Native Americans from various tribes – the Nez Perce, Yakama, Umatilla, Cayuse, and Walla Walla – and, through a combination of persuasion, pressure, and sometimes dubious translation, secured vast land cessions. The treaties established reservations, ostensibly protecting tribal lands, but crucially opened up enormous swathes of territory for American settlement. Stevens believed he had achieved a diplomatic masterpiece, paving the way for peaceful expansion.

However, the ink was barely dry on these agreements before the seeds of conflict were sown. The very treaties Stevens had engineered were, from the Native perspective, deeply flawed and often misunderstood. Many chiefs believed they were granting rights of passage, not outright ownership, or that the land cessions were temporary. More critically, Stevens had promised that the ceded lands would remain closed to white settlement until surveyed and officially opened – a promise almost immediately violated.

The true catalyst for the Second Walla Walla Council, and indeed the subsequent wars, was the discovery of gold. Not long after the 1855 treaties, prospectors flooded into the Fraser River region of British Columbia and other areas, inevitably traversing and often squatting on lands designated as Native American territory, including those purportedly protected by the new treaties. These miners, often lawless and contemptuous of Native rights, brought disease, liquor, and violence, pushing the Indigenous inhabitants to the brink.

"The white man," Chief Kamiakin of the Yakama, a powerful and sagacious leader, had reportedly warned at the First Council, "will soon crowd us from our homes." His prophecy was unfolding with terrifying speed. The Yakama, Cayuse, and Walla Walla, already wary of Stevens’s intentions, saw their lands overrun and their hunting grounds despoiled. Their appeals to Stevens for enforcement of the treaties fell on deaf ears. Instead, Stevens, viewing the Native resistance as an impediment to progress, declared martial law and dispatched military forces.

This escalating tension culminated in a series of skirmishes that quickly spiraled into full-blown war, particularly the Yakima War. It was against this backdrop of open hostilities that Governor Stevens, ever the pragmatist, called for a second council at Walla Walla in April 1856. His stated aim was to "reconcile" the tribes and solidify the terms of the 1855 treaties, but his underlying objective was to reassert American authority and force compliance.

The atmosphere at the Second Walla Walla Council was palpably different from its predecessor. There were no grand pronouncements of peace, no optimistic visions of shared prosperity. Instead, a heavy cloud of distrust and resentment hung over the proceedings. Stevens arrived with a substantial military escort, a clear show of force that did little to assuage Native suspicions. Many of the most defiant chiefs, including Kamiakin, were conspicuously absent, having already committed to armed resistance. Others, like Chief Looking Glass of the Nez Perce, who had initially been inclined towards peace, were now deeply skeptical.

The Council itself was a tense and often acrimonious affair. Stevens, still confident in his authority, lectured the assembled chiefs, accusing them of breaking faith and demanding their submission. He reiterated the terms of the 1855 treaties, largely ignoring the grievances of the tribes regarding the influx of miners and the failure to protect their lands.

The Native leaders present, though fewer in number and perhaps less unified than before, nevertheless voiced their profound anger and sense of betrayal. They spoke of the broken promises, the desecration of sacred lands, and the unpunished violence against their people. For them, the treaties were not instruments of peace but tools of dispossession, forced upon them under duress.

One of the most poignant aspects of this council was the absence of Chief Peopeomoxmox of the Walla Walla, who had been a prominent figure at the first council. Tragically, he had been taken captive by volunteer soldiers in December 1855 and brutally killed, his body mutilated. His death, a stark symbol of the escalating violence and disregard for Native lives, cast a long shadow over the proceedings, underscoring the futility of peaceful negotiation when such atrocities were being committed.

The Nez Perce, led by the pragmatic Chief Lawyer, found themselves in an unenviable position. While some of their warriors had joined the fighting, Lawyer believed that continued resistance would only lead to further destruction for his people. He argued for a path of accommodation, hoping to salvage what they could through diplomacy. This internal division within the Native ranks further complicated the council, playing directly into Stevens’s hands.

Ultimately, the Second Walla Walla Council was a catastrophic failure. No new agreements were reached, and no reconciliation was achieved. Stevens’s unwavering stance, coupled with the deep-seated anger and fear of the Native tribes, ensured that the chasm between them only widened. The council concluded not with handshakes and renewed promises, but with a chilling reaffirmation of the impending conflict. Stevens, frustrated by the lack of capitulation, returned to his duties with an even firmer resolve to subdue the "hostile" tribes by force.

The immediate aftermath was devastating. The failure of the Second Walla Walla Council plunged the Pacific Northwest into years of intense and brutal conflict known as the Yakima War, the Cayuse War, and other localized struggles. Native American communities suffered immense losses in terms of lives, land, and cultural heritage. Warriors fought bravely, but they were ultimately outmatched by the superior firepower and relentless pressure of the U.S. military. Many tribes were forcibly removed from their ancestral lands, confined to ever-shrinking reservations, and subjected to policies designed to eradicate their traditional ways of life.

The legend of the Second Walla Walla Council, therefore, is not a story of a glorious victory, but a somber tale of a crucial turning point. It stands as a powerful symbol of the clash between expansionist ambition and Indigenous sovereignty, a stark reminder of the tragic consequences when diplomacy fails and promises are broken. It embodies the darker, more complex threads in America’s tapestry of legends – the stories of injustice, resistance, and the profound human cost of nation-building.

Today, the legacy of the Second Walla Walla Council endures in the collective memory of the Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest, who continue to fight for their rights, preserve their cultures, and ensure their voices are heard. It serves as a potent reminder that the "legends of America" are not monolithic. They are multifaceted, often contradictory, and demand a nuanced understanding of history from all perspectives. This "shadow council" teaches us that some of the most enduring legends are not those of unblemished heroism, but those that illuminate the painful truths and enduring struggles that have shaped the very soul of the nation. It is a legend that continues to challenge us to confront our past, acknowledge its complexities, and strive for a more just future.