The Shadow of the Lode: William Comstock, Scion of Silver and Scourge of the West

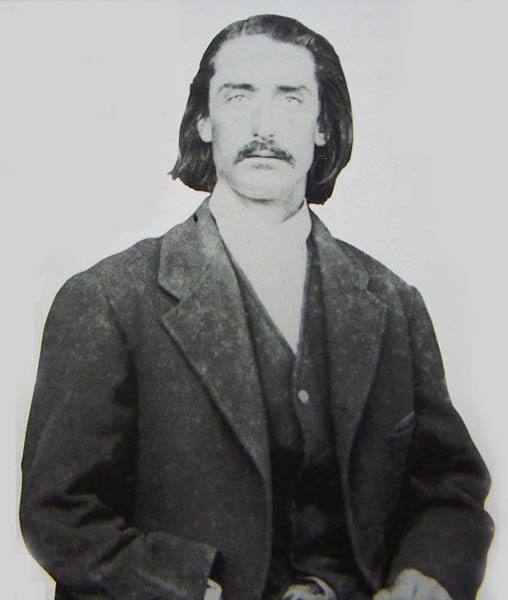

In the annals of the American West, where legends were forged in the crucible of gold dust and gunpowder, few figures embodied the era’s volatile spirit quite like William Comstock. Not the discoverer of the famed Comstock Lode, nor a celebrated lawman or notorious outlaw in the mold of Billy the Kid, William Comstock was instead a peculiar product of the frontier: a man born into privilege yet destined for a life of violence, a scion whose name echoed with unimaginable wealth, but whose personal narrative was stained with blood and marked by an enduring reputation as a dangerous, quick-tempered bully. His story is a compelling, if dark, reflection of a time when justice was often swift, and a quick draw could define, or end, a man’s existence.

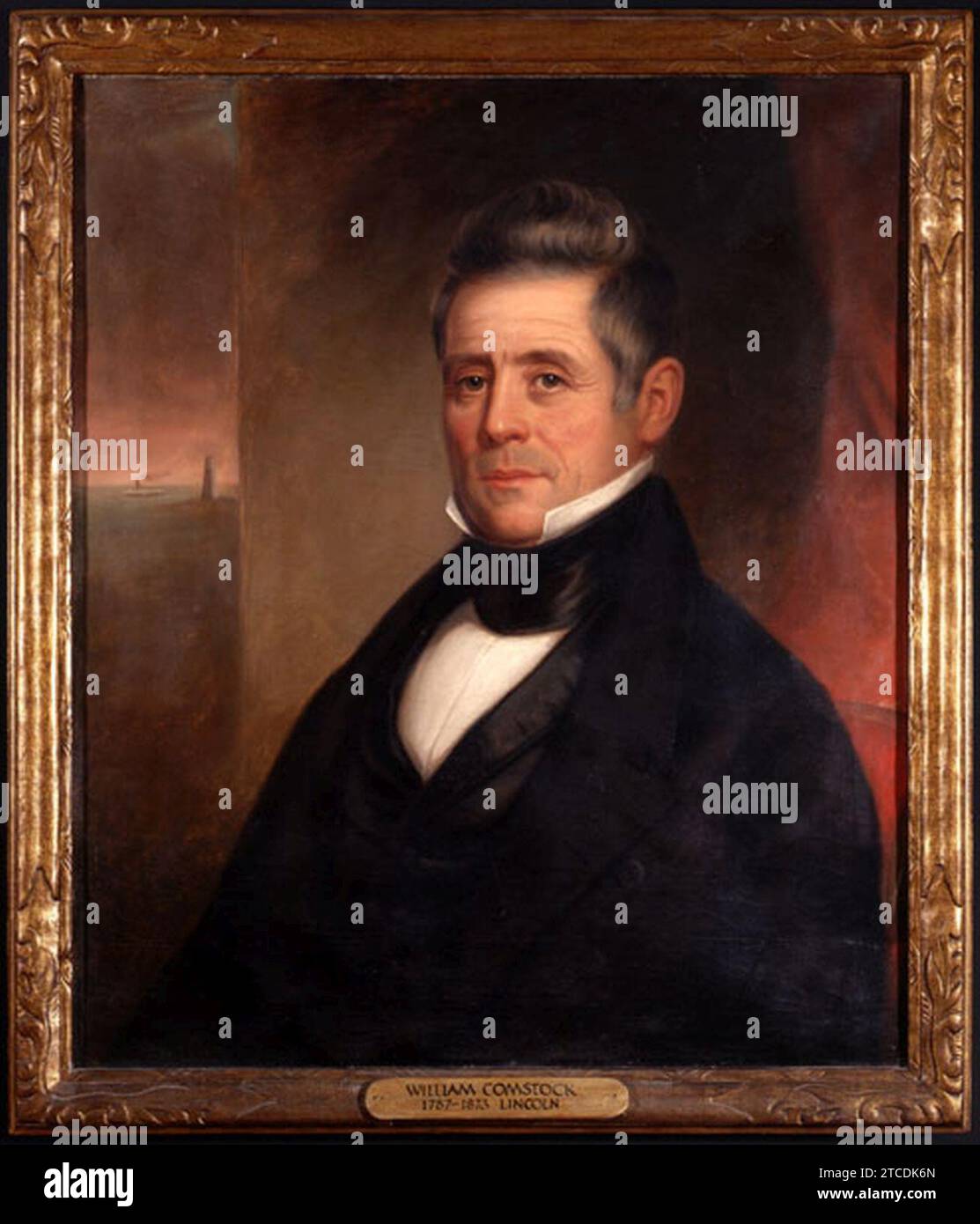

Born around 1845, William Comstock was the son of George Comstock, a prominent figure in the early days of Nevada. George was a brother to Henry T. P. Comstock, the colorful and somewhat erratic prospector whose name, through a series of complex circumstances, became indelibly linked to the "Comstock Lode" – the richest silver strike in American history. While Henry Comstock himself died in poverty, his surname became synonymous with unimaginable wealth, transforming Virginia City, Nevada, into a bustling, boisterous, and often lawless metropolis.

This was the world William Comstock was born into. He grew up in the shadow of his family’s controversial legacy, surrounded by the cacophony of clanging picks, the shouts of speculators, and the ever-present gleam of silver. Unlike many who clawed their way to wealth, William inherited a degree of status and a family name that opened doors, but it also seemed to fuel a sense of entitlement and a propensity for trouble. From a young age, he cultivated a reputation as a difficult man, quick to anger, and prone to settling disputes with his fists or, more ominously, with a firearm.

His early life was a whirlwind of gambling halls, saloons, and various, often ill-fated, ventures. He dabbled in mining, tried his hand at politics, even serving a brief, tumultuous term as a sheriff in Eureka County, Nevada. However, any attempts at a respectable career were invariably overshadowed by his volatile personality and his penchant for confrontation. "He was a man who lived on the edge," one contemporary account might have read, "always spoiling for a fight, always ready to prove his mettle, often to the detriment of those around him."

The defining event of William Comstock’s early notoriety, and perhaps the one that etched his name most deeply into the local lore, occurred in Virginia City on July 18, 1871. The victim was none other than his cousin, Harry Comstock. Harry, a younger man and another relative of the famous Henry, was considered by many to be the rightful "heir" to the Comstock name and its associated, albeit largely symbolic, prestige. There had long been animosity between the two cousins, fueled by a mixture of family rivalry, personal slights, and the corrosive influence of alcohol and the frontier’s free-wheeling culture.

On that fateful summer evening, the two men were drinking in a saloon when an argument erupted, escalating quickly from heated words to threats. Accounts differ slightly on the precise trigger, but the core narrative remains: William Comstock, known for his readiness to resort to violence, pulled a pistol and shot Harry Comstock. The bullet found its mark, and Harry fell, mortally wounded.

The shooting sent shockwaves through Virginia City. While violence was not uncommon, the killing of one Comstock by another, especially one so prominent as William, was a sensation. William was arrested, and a trial ensued, captivating the attention of the populace. His defense hinged on the claim of self-defense, portraying Harry as the aggressor and William as merely protecting himself from a perceived threat. Furthermore, the defense subtly leveraged William’s family influence and the general acceptance of frontier justice, where a man’s honor and the right to defend oneself were paramount.

The verdict, though controversial, was perhaps predictable for the time and place: William Comstock was acquitted. The outcome solidified his reputation as a man not to be trifled with, someone who could kill and walk free. It reinforced the notion that in the Wild West, a powerful name, a good lawyer, and a reputation for dangerousness could sometimes be enough to escape the hangman’s noose. Yet, while he was legally exonerated, the stain of the killing would follow him.

Virginia City, for all its glitter, eventually proved too small, or perhaps too hot, for William Comstock. Like many who found themselves on the wrong side of too many altercations, he sought new opportunities, or perhaps just new trouble, on the ever-moving frontier. He drifted east, eventually landing in the booming cattle towns of Kansas, a new crucible of violence and opportunity where cowboys, gamblers, and outlaws converged.

By the mid-1870s, Ellsworth, Kansas, was one such town. It was a chaotic, dust-choked hub where cattle drives ended, fortunes were made and lost, and disputes were frequently settled with lead. Here, William Comstock, still carrying the weight of his Nevada past, continued his pattern of drinking, gambling, and confrontation. It was here, in the autumn of 1873, that he would meet his ultimate fate, at the hands of another infamous "Billy the Kid" – though not the one whose legend would become synonymous with New Mexico.

The "Billy the Kid" who ended William Comstock’s life was William "Billy" Thompson, a notorious gunfighter and brother of the equally famous gunman, Ben Thompson. Billy Thompson, like Comstock, was a man prone to violence, quick on the trigger, and a formidable opponent. The stage was set for an inevitable clash of titans, two men whose reputations for deadliness preceded them.

The confrontation occurred on August 15, 1873. Accounts vary, but the general consensus is that Comstock and Thompson, along with several others, were drinking in a saloon, their tempers likely frayed by alcohol and the oppressive Kansas heat. An argument flared up, possibly over a card game, a perceived slight, or simply the explosive chemistry between two such volatile personalities.

As the argument escalated, Thompson, known for his lightning-fast draw, produced a pistol and fired. The shot struck William Comstock, who fell. He died shortly thereafter, succumbing to his wound. The irony was palpable: a man who had killed and walked free, a man who had built a fearsome reputation, was himself cut down in a saloon brawl, a common, almost mundane, end for many who lived by the gun in the Wild West.

Billy Thompson, after the shooting, fled Ellsworth. He was pursued by law enforcement, including the famous Wyatt Earp, who was then a deputy in Ellsworth. Thompson was eventually apprehended and brought to trial. Like Comstock before him, Thompson’s defense sought to cast doubt on the prosecution’s case, arguing self-defense or, in Thompson’s particular instance, an "insanity" defense, claiming he was not of sound mind due to alcohol and the heat of the moment. The outcome, again, reflected the peculiar nature of frontier justice: Thompson was acquitted. The two men, Comstock and Thompson, were both killers who walked free, only to meet their ends in a similar fashion – violence begetting violence.

William Comstock’s life, a turbulent saga of privilege, violence, and a relentless pursuit of trouble, serves as a vivid, if dark, chapter in the narrative of the American frontier. He was not a hero, nor a purely villainous figure, but a complex individual shaped by his environment and his own destructive tendencies. His story underscores the brutal realities of the Wild West, where a name could bring both opportunity and a target on one’s back, where family ties could be a source of both power and deadly rivalry, and where a man’s reputation, once forged in blood, could follow him to the grave.

In the end, William Comstock, the son of a prominent Nevada family, the killer acquitted, the man who dared to challenge the notorious Billy Thompson, faded into the larger tapestry of Western history. His legacy is not one of discovery or lawmaking, but rather a cautionary tale, a testament to the fact that even in an era defined by grand narratives of progress and expansion, some lives were simply destined to be consumed by the very chaos they embraced. He remains, forever, a shadow of the Lode, a man whose name was synonymous with wealth, but whose life was ultimately defined by the stark, unforgiving currency of the gun.