The Shadow of the Rope: America’s Lynching Legacy

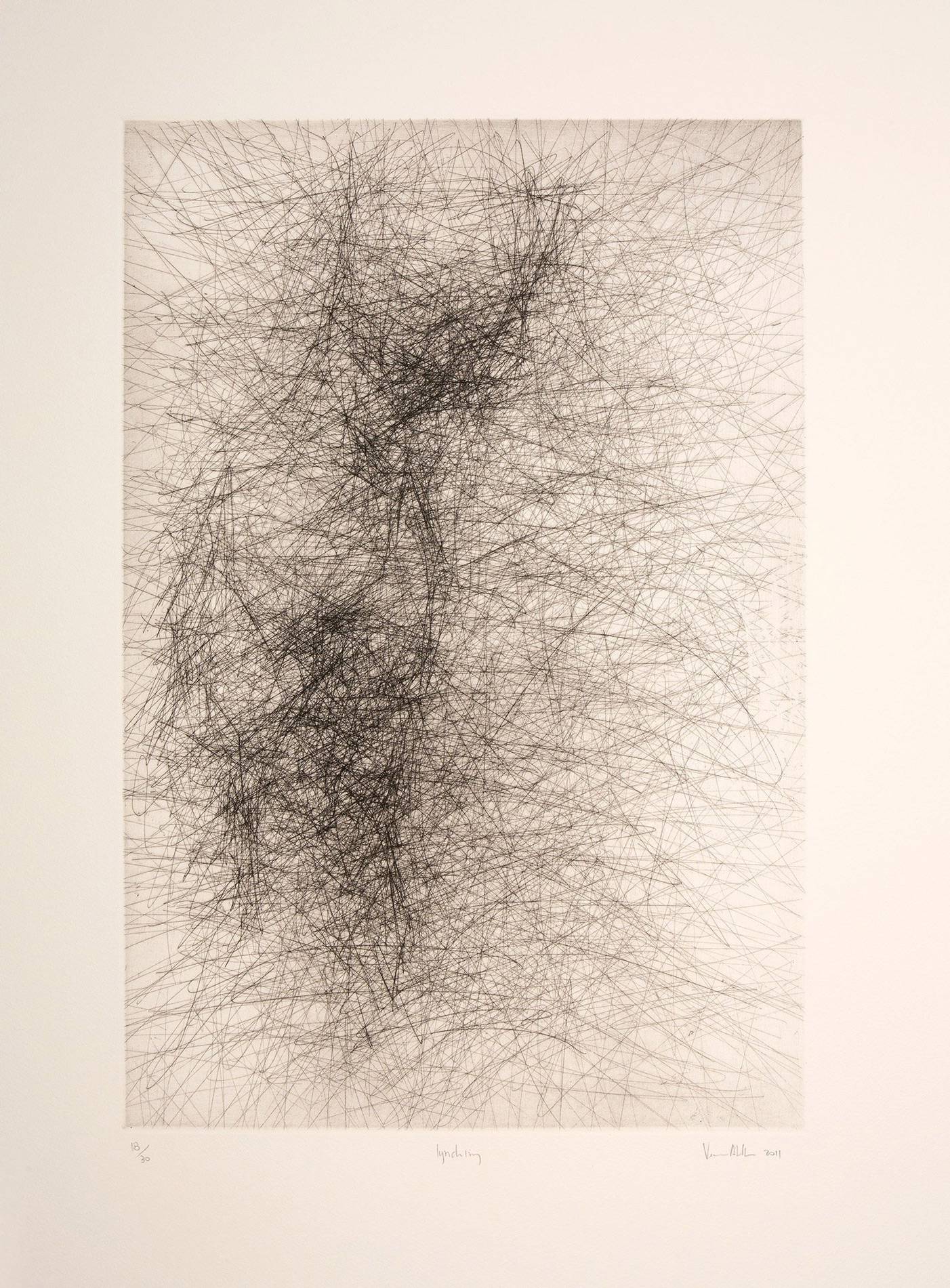

The image is seared into the collective memory of a nation, even if many prefer to look away: a Black man, or sometimes a woman, hanging from a tree, a bridge, or a lamppost, surrounded by a gleeful, often picnicking crowd of white men, women, and children. Postcards were sometimes made of these gruesome events, bought and sent as macabre souvenirs. This was lynching – a brutal, public, and extra-judicial form of racial terror that cast a long, dark shadow over American history, particularly from the late 19th to the mid-20th century. It was not merely an act of violence; it was a ritual of intimidation, a spectacle of white supremacy, and a chilling testament to the systemic failure of justice.

From 1877 to 1950, more than 4,400 African Americans were victims of racial terror lynchings in the United States, according to research by the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI). These were not isolated acts of vigilante justice but rather a widespread campaign of terror, designed to enforce racial hierarchy and suppress Black aspirations following the Civil War and the Reconstruction era. As the promise of Reconstruction faded and Jim Crow laws solidified racial segregation and disenfranchisement, lynching emerged as a primary tool to maintain white dominance.

The Genesis of Terror: Post-Reconstruction America

The end of the Civil War brought freedom to millions of enslaved people, but it also ushered in a period of intense racial animosity and economic upheaval. White Southerners, reeling from defeat and the perceived threat to their social order, resisted Black progress with increasing violence. The Ku Klux Klan and similar white supremacist groups rose to power, using terror to intimidate Black voters, suppress economic independence, and enforce racial norms. While lynchings occurred before and after this period, the post-Reconstruction era saw their proliferation as a form of "community justice" – a euphemism for mob rule that circumvented legal processes.

The vast majority of victims were Black men, often accused of crimes ranging from murder and rape to theft, insulting a white person, or even simply "standing up to a white man." However, the accusations were often flimsy, fabricated, or disproportionate to the alleged offense. The charge of sexually assaulting white women, in particular, became a pervasive and potent myth, used to justify horrific violence and dehumanize Black men.

The Spectacle of Cruelty: A Public Display

What distinguished lynching from other forms of murder was its public, often theatrical nature. Mobs, sometimes numbering in the thousands, would gather, often alerted by local newspapers or word of mouth. These were not clandestine operations; they were community events, attended by families, with children sometimes excused from school to witness the spectacle. Victims were frequently tortured, mutilated, burned, and then hanged, their bodies left on display for hours or even days as a warning to other Black people.

Bryan Stevenson, founder and executive director of the EJI, aptly describes it: "Lynching was a violent public spectacle, a tool of social control that reinforced white supremacy and terrorized African Americans into submission." The sheer brutality was intended to send a clear message: defy the racial order, and you would face unspeakable consequences. Law enforcement officials, local politicians, and even judges were often complicit, either actively participating in the mobs or passively allowing them to operate without intervention. Arrests and prosecutions of lynchers were exceedingly rare, creating a climate of impunity that further emboldened the perpetrators.

One of the most chilling aspects was the normalization of this violence. Photographs of lynchings were widely circulated, often depicting smiling white faces posing with the victim’s body. These images, now stark reminders of a brutal past, were then consumed as entertainment and affirmation of white power. The trade in postcards depicting these scenes, as well as body parts taken as souvenirs, highlights the depth of depravity and the dehumanization of the victims.

Ida B. Wells and the Anti-Lynching Crusade

Against this backdrop of terror, brave voices emerged to challenge the system. One of the most prominent was Ida B. Wells, a fearless journalist and activist. Born into slavery in Mississippi, Wells became a newspaper editor in Memphis, Tennessee. Her investigative journalism meticulously documented the true nature of lynchings, debunking the pervasive myth that they were primarily in response to sexual assault.

In 1892, after three of her friends were lynched in Memphis, Wells launched an international anti-lynching campaign. Her findings, published in pamphlets like "Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases" and "A Red Record," revealed that lynchings were most often motivated by economic competition, political power, or minor social transgressions, rather than actual crimes. She famously declared, "Nobody in this section of the country believes the old threadbare lie that Negro men rape white women. If Southern white men are not careful, they will overreach themselves and public sentiment will have a reaction." Her unwavering courage made her a target, forcing her to relocate to the North, but her work laid the foundation for the organized anti-lynching movement.

The Fight for Federal Intervention

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), founded in 1909, made the passage of federal anti-lynching legislation a cornerstone of its early agenda. Leaders like Walter White, who often risked his life by infiltrating white supremacist groups and investigating lynchings in the South, tirelessly lobbied Congress. White, who was fair-skinned and could pass for white, conducted 41 investigations into lynchings and race riots, often providing the only accurate accounts of these atrocities.

Despite decades of persistent effort, including the introduction of the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill in the 1920s, federal anti-lynching legislation repeatedly failed to pass. Southern Democrats, wielding immense power through the filibuster in the Senate, consistently blocked these bills, arguing that lynching was a state issue and federal intervention would infringe on states’ rights. This political deadlock left African Americans vulnerable and underscored the federal government’s complicity through inaction. It wouldn’t be until 2022 that the Emmett Till Antilynching Act was finally signed into law, a symbolic victory decades too late for its intended victims.

The Enduring Legacy: Trauma, Migration, and Reckoning

While the frequency of lynchings declined significantly by the mid-20th century, largely due to the efforts of the Civil Rights Movement, changing social norms, and the increasing national scrutiny, the legacy of this terror continues to haunt America.

One profound consequence was the Great Migration, where millions of African Americans fled the violent oppression of the South for the perceived safety and opportunity of Northern and Western cities. This demographic shift reshaped American society, but the trauma of lynching, the fear, and the memory of lost loved ones remained deeply embedded in the psyche of Black communities. Generations grew up with stories of terror, fostering a profound distrust of the legal system and a persistent sense of vulnerability.

Today, there is a growing national effort to confront this painful history. The EJI’s National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama, often referred to as the "Lynching Memorial," stands as a powerful testament to the victims. Its 800 corten steel monuments, each representing a U.S. county where a racial terror lynching took place, bear the names of the victims, forcing visitors to confront the scale and specificity of the violence. Stevenson asserts, "We cannot heal the deep wounds of our racial past until we tell the truth about it."

The shadow of the rope extends beyond the physical act of lynching. It illuminates the roots of systemic racism, the historical denial of justice, and the enduring impact of state-sanctioned violence on racial disparities that persist today. From police brutality to mass incarceration, the echoes of a system designed to control and suppress Black lives can still be heard. Acknowledging and understanding the history of lynching is not about shaming the present generation, but about understanding how the past shaped the present, and how a nation can work towards a more just and equitable future. Only by confronting the full horror of this chapter can America truly begin to heal its deep, historical wounds.