The Shadow on the Plains: Bob Dozier and America’s Enduring Outlaw Legends

America, a nation forged in rebellion and shaped by the vastness of its frontiers, has always been fertile ground for legends. From the stoic heroism of Davy Crockett to the larger-than-life exploits of Paul Bunyan, our collective consciousness is saturated with tales that blur the line between fact and folklore. Yet, perhaps no archetype holds a more enduring, complex grip on the American imagination than the outlaw. These figures, whether gun-slinging cowboys or slick urban criminals, embody a defiant individualism, a rejection of authority that resonates deeply in a culture that champions freedom. While names like Jesse James, Billy the Kid, and John Dillinger echo through history with romanticized notoriety, there are other, perhaps lesser-known, figures whose brief, explosive careers carve their own dark niche in the national tapestry of myth. One such figure is Bob Dozier, an Oklahoma outlaw whose audacious escape and subsequent years as a phantom on the run briefly cemented his place as a modern-day folk devil, a testament to America’s unyielding fascination with those who dare to slip through the grasp of the law.

The American outlaw is more than just a criminal; they are a cultural construct, a projection of societal anxieties and desires. In the post-Civil War era, figures like Jesse James, a Confederate guerrilla turned bank robber, became symbols of resistance against perceived Northern oppression and corporate greed. His legend, fueled by dime novels and sensationalized newspaper accounts, painted him as a latter-day Robin Hood, despite ample evidence of his brutality. Billy the Kid, a young, charismatic killer in the chaos of the New Mexico Territory, embodied the untamed spirit of the West, his short, violent life ending in a blaze of glory that secured his immortality in lore.

By the 20th century, as the frontier closed and urbanization took hold, the outlaw evolved. John Dillinger, "Public Enemy No. 1" during the Great Depression, was a suave bank robber whose daring escapes and theatrical flair captured the public’s imagination. He was seen by many as a rebel against the very banks that had plunged the nation into economic despair, a modern rogue thumbing his nose at the establishment. Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow, a pair of star-crossed lovers on a murderous crime spree, became tragic anti-heroes, their exploits immortalized in song and film, embodying a desperate defiance against a system that offered little hope to many.

These figures, from the horse-mounted bandit to the machine-gun wielding gangster, share common threads: a life lived outside the law, often marked by violence; a knack for evading capture; and, crucially, a narrative that transcends their criminal acts, transforming them into something larger than life. They represent a dark individualism, a romanticized rejection of the societal norms, a fleeting moment of power in the face of overwhelming authority. It is into this pantheon, albeit a more shadowy corner of it, that Bob Dozier briefly strode.

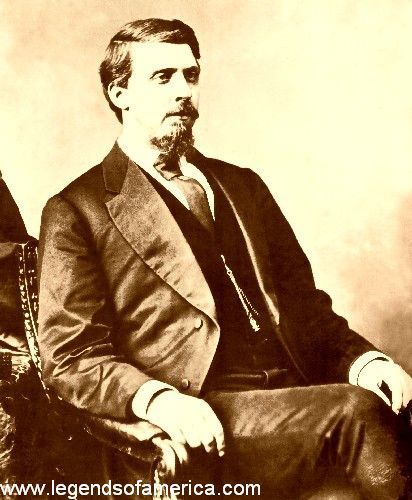

Robert Wayne Dozier was not a charismatic bank robber or a legendary gunfighter. Born in 1947, his criminal career was rooted in the grittier, less romantic world of drug trafficking. A native of Oklahoma, Dozier became involved in the burgeoning methamphetamine trade, a dangerous, lucrative enterprise that operated largely outside the public eye, far from the sensational headlines of Depression-era bank heists. His story escalated dramatically on August 21, 1981, when, during a drug deal gone wrong in Oklahoma City, Dozier murdered Kevin Black, a 28-year-old Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) agent. The brutal slaying of a federal officer immediately thrust Dozier into a category far more serious than a mere drug dealer; he was now a cop killer, a target of the highest priority for law enforcement.

Dozier was swiftly apprehended, tried, and convicted for Agent Black’s murder, receiving a life sentence. He was incarcerated at the Federal Medical Center (FMC) in Lexington, Kentucky, a facility not known for its maximum-security features, housing inmates with medical or psychiatric needs. This detail, seemingly innocuous, would prove pivotal in Dozier’s transformation from convicted murderer to elusive legend.

On the night of October 28, 1982, Robert Wayne Dozier did the unthinkable: he escaped. Using makeshift tools – a sharpened spoon, a piece of wire – he meticulously picked the lock of his cell, then painstakingly worked his way through a ventilation shaft. He then used a rope fashioned from bedsheets to scale down the exterior wall of the facility. The escape was audacious, a testament to his ingenuity, patience, and sheer will. It wasn’t a prison riot or a dramatic shootout; it was a silent, almost ghost-like vanishing act, executed with a methodical precision that sent shockwaves through federal law enforcement.

The escape of a convicted federal agent killer from a seemingly secure facility was a national embarrassment and a major security threat. Dozier immediately landed on the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted Fugitives list. The manhunt that ensued was intense, a dragnet spread across multiple states. Every tip, every lead, every shadowy figure seen disappearing into the night was scrutinized. For the authorities, Dozier was a dangerous fugitive who needed to be brought to justice. For the public, particularly in Oklahoma and surrounding states, he began to morph into something else.

The very act of his escape, the cleverness and audacity of it, became the stuff of legend. How could a man simply vanish? The narrative wasn’t about his crime anymore, but about his elusiveness. He became a phantom, a whisper on the wind. The fact that he was a cop killer didn’t romanticize him, but it added a darker, more dangerous edge to his legend. He wasn’t a charming rogue; he was a cunning, dangerous man who had outsmarted the system, at least temporarily.

This ability to escape and evade, to become a "ghost," is a hallmark of many American outlaw legends. Jesse James famously evaded capture for years, disappearing into the vastness of the post-war South. John Dillinger’s breakout from the seemingly impregnable Crown Point jail using a wooden gun became an instant classic of criminal folklore. Dozier, though lacking the historical context of a James or the media savvy of a Dillinger, tapped into this deep-seated American fascination with the individual who can slip through the net. He was a modern-day trickster, a dark spirit demonstrating the fallibility of even the most powerful institutions.

The years following Dozier’s escape were marked by a pervasive unease. He was spotted, or rumored to be spotted, in various locations, always just out of reach. His freedom became a symbol of law enforcement’s frustration, a silent challenge to their authority. For over three years, Robert Wayne Dozier lived as a fugitive, his existence a testament to the sheer difficulty of capturing a determined individual in a vast and interconnected country. He was, in a sense, a dark version of the frontier explorer, navigating a new kind of wilderness – the hidden networks and anonymity of modern America.

His legend, however, was not built on daring robberies or acts of social rebellion. It was built on the simple, yet profound, act of not being caught. He represented the dark inverse of the American dream – not the pursuit of success, but the pursuit of absolute freedom, even if it meant a life on the run. The media, though less prone to outright glorification than in earlier eras, still played its part. Every news report on the ongoing manhunt, every "most wanted" poster, inadvertently amplified his status, transforming a convicted murderer into a modern-day bogeyman, a symbol of the dangerous unknown.

The elusive chapter of Bob Dozier’s life came to an end on March 27, 1986, in San Antonio, Texas. After years of relentless pursuit, federal agents finally cornered him. He was recaptured without incident, his days as a phantom finally over. The reality of his capture, quiet and undramatic, stood in stark contrast to the audacious escape that had defined his notoriety. He returned to federal custody, eventually dying in prison in 2011.

Yet, even in his quiet recapture and death behind bars, Bob Dozier’s brief moment as an elusive outlaw endures. His story, though not as widely celebrated or romanticized as those of Jesse James or John Dillinger, serves as a powerful reminder of America’s ongoing engagement with its outlaw legends. He was not a hero, not even an anti-hero in the traditional sense, but his sheer defiance, his ability to disappear, briefly made him a compelling, if unsettling, figure.

The legends of America, whether they speak of brave pioneers, mythical creatures, or defiant outlaws, reflect our collective hopes, fears, and values. They are the stories we tell ourselves to understand who we are and what we cherish. Bob Dozier, the Oklahoma outlaw who murdered a federal agent and then slipped into the shadows for years, reminds us that this fascination extends even to the darkest corners of human experience. His legend is not one of glory, but of cunning and evasion, a testament to the enduring power of the individual who, for a fleeting moment, manages to outwit the overwhelming force of the law, forever etching their shadow on the vast, myth-laden plains of American history.