The Shadow on the Stage: John Wilkes Booth and America’s Enduring Scar

The night of April 14, 1865, was meant to be one of jubilation in Washington D.C. The Civil War, a conflict that had torn the nation asunder, had finally ended, and President Abraham Lincoln, the stoic leader who had guided the Union through its darkest hours, sought a moment of respite at Ford’s Theatre. Yet, in the wings, a different kind of drama was unfolding, orchestrated by a man whose name would forever be synonymous with American infamy: John Wilkes Booth. A celebrated actor, scion of a theatrical dynasty, Booth would, in a single, audacious act, plunge a grieving nation into deeper sorrow, forever etching his name into the dark annals of history as the assassin of a president.

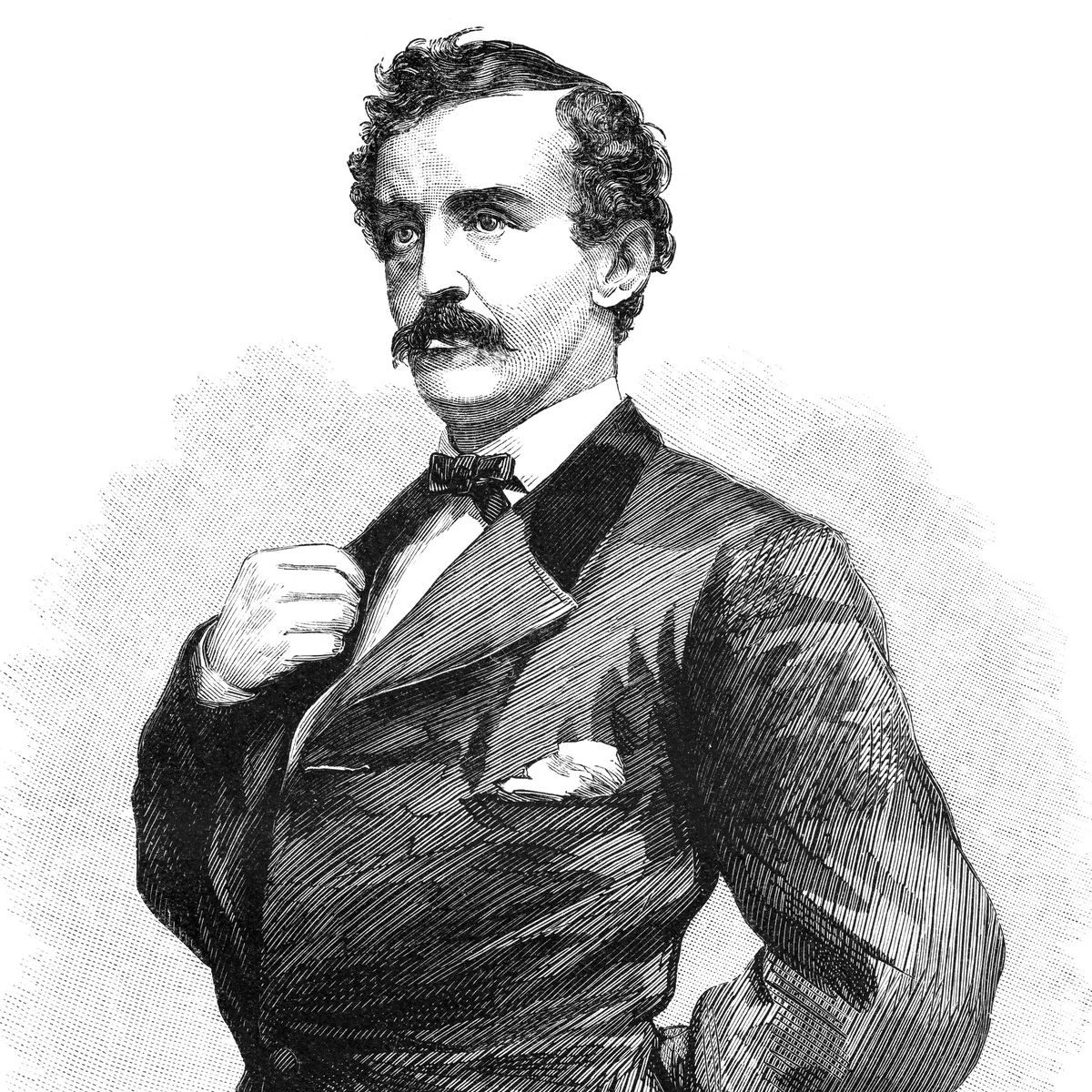

Born in 1838 near Bel Air, Maryland, John Wilkes Booth was the ninth of ten children to the renowned Shakespearean actor Junius Brutus Booth and his mistress, Mary Ann Holmes. The Booth name was synonymous with the stage; his older brothers, Edwin and Junius Brutus Jr., were also acclaimed actors, with Edwin widely considered the greatest American actor of his generation. John Wilkes himself possessed striking good looks, a charismatic stage presence, and a talent that garnered him considerable fame, particularly in the South. He was known for his athletic performances, his powerful voice, and an intensity that captivated audiences. Yet, beneath the veneer of theatrical brilliance lay a fervent, almost fanatical, devotion to the Southern cause and an escalating hatred for Abraham Lincoln.

Booth’s political convictions were deeply ingrained. Maryland, a border state, was a hotbed of divided loyalties, and Booth, despite his Northern birthplace, was an ardent Confederate sympathizer and a staunch advocate for slavery. He viewed Lincoln not as a savior of the Union, but as a tyrant, a dictator who had waged war against his beloved South and threatened its very way of life. This ideological fervor was not merely passive; Booth actively participated in Confederate activities, engaging in smuggling and espionage for the Southern cause. He was present at the execution of abolitionist John Brown in 1859, a deeply formative experience that cemented his belief in the righteousness of the Southern slaveholding society. "I have ever regarded Lincoln as a criminal," he would later write in his diary, "and by every law of God and man, he was not only deserving of death, but I think he should have been killed long ago."

As the war drew to a close and the Confederacy’s defeat became inevitable, Booth’s despair and rage intensified. He saw the Union victory not as a triumph of liberty, but as the destruction of a cherished way of life and an unforgivable assault on states’ rights. He initially conceived a plan to kidnap Lincoln, transporting him to Richmond to be exchanged for Confederate prisoners of war. He gathered a small group of conspirators – David Herold, a young accomplice; George Atzerodt, a German immigrant tasked with killing Vice President Andrew Johnson; and Lewis Powell (alias Lewis Paine), a powerful, fanatical ex-Confederate soldier assigned to assassinate Secretary of State William H. Seward.

Several attempts at the kidnapping plot failed, but Booth remained undeterred. The turning point came on April 11, 1865, when Lincoln delivered his last public address. In it, the President spoke of reconstruction and, crucially for Booth, hinted at extending suffrage to Black soldiers and "very intelligent" Black men. For Booth, a virulent white supremacist, this was the ultimate betrayal, an unforgivable act that sealed Lincoln’s fate. "That means nigger citizenship," he reportedly seethed to Herold. "Now, by God, I’ll put him through." The kidnapping plot transmuted into a darker, deadlier scheme: assassination.

Ford’s Theatre, where Booth often performed, became the stage for his final, most infamous act. He knew the theatre intimately – its passages, its secret routes, even the precise location of the President’s private box. On the fateful night of April 14, Good Friday, as Lincoln arrived to see the comedy "Our American Cousin," Booth was already laying his final preparations. He drilled a peephole into the door of the presidential box and secured it with a wooden brace, ensuring no one could easily enter after him. He even spoke briefly with Lincoln’s footman, perhaps lulling any suspicion.

At around 10:15 PM, during a moment in the play when a single actor was on stage, delivering a line that traditionally drew laughter, Booth made his move. He slipped into the presidential box, unobserved. Lincoln, accompanied by his wife Mary Todd Lincoln, Major Henry Rathbone, and Clara Harris, was seated, enjoying the performance. Booth raised his Derringer pistol, aimed it at the back of Lincoln’s head, and fired. The small, lead ball lodged behind Lincoln’s left eye.

A moment of stunned silence was shattered by the crack of the pistol and Mary Lincoln’s scream. Major Rathbone lunged at Booth, who slashed him with a knife, severing an artery in his arm. "Sic semper tyrannis!" (Thus always to tyrants!), Booth allegedly cried, the motto of Virginia, as he leaped from the box to the stage below. Though the leap was dramatic, his spur caught on a flag, causing him to land awkwardly and break his left fibula. Despite the injury, the charismatic actor managed a theatrical bow – some accounts suggest his cry was more like "The South is avenged!" or simply "Sic semper!" – before limping across the stage and disappearing into the night through the theatre’s back door. Chaos erupted, but Booth, aided by Herold, who had prepared horses, vanished into the darkness.

The manhunt for Booth was unprecedented in American history. A reward of $100,000 was offered, the largest ever at the time. Booth and Herold fled south through Maryland, seeking refuge with Confederate sympathizers. Their journey was arduous, fraught with pain from Booth’s broken leg and the constant fear of discovery. They stopped at the home of Dr. Samuel Mudd, a local physician who set Booth’s leg, a decision that would later lead to Mudd’s imprisonment for complicity.

As days turned into a week, Booth’s physical condition worsened, and his mental state became increasingly agitated. His diary entries from this period reveal a man grappling with the enormity of his act, yet still convinced of its righteousness. "I am here in despair," he wrote on April 21st. "And why? For doing what Brutus was honored for—what great Washington fought for." He saw himself as a hero, a liberator, tragically misunderstood by a world that had turned against him. "God cannot pardon me if I have done wrong," he penned, "but I am sure that I have not."

The fugitives eventually made their way to Richard Garrett’s farm in rural Virginia, where they hid in a tobacco barn. On April 26, eleven days after the assassination, Union cavalry troops, led by Lieutenant Edward P. Doherty, surrounded the barn. Herold surrendered, but Booth, defiant to the last, refused to come out. "I will not be taken alive!" he shouted. The barn was set ablaze, hoping to flush him out. As the flames engulfed the structure, Sergeant Boston Corbett, acting against orders to take Booth alive, fired his pistol, striking Booth in the neck.

Booth collapsed, paralyzed. He was dragged from the burning barn and laid on the porch of the Garrett farmhouse, where he lingered for several hours. His last words, whispered as he looked at his hands, were reportedly, "Useless, useless." He died shortly after 7:00 AM on April 26, 1865, bringing an end to the life of America’s most infamous assassin.

The aftermath of Booth’s act was catastrophic. Lincoln died the following morning, plunging the nation into profound grief and uncertainty. The assassination sent shockwaves around the world and irrevocably altered the course of American history. Booth’s co-conspirators were swiftly apprehended, tried by a military commission, and four – Lewis Powell, David Herold, George Atzerodt, and Mary Surratt (who ran a boarding house where the conspirators met) – were hanged on July 7, 1865. Dr. Mudd and others received lengthy prison sentences.

John Wilkes Booth’s legacy remains one of unparalleled infamy. He is remembered not for his theatrical talent, but for his singular act of violence that robbed a nation of its leader at its most vulnerable moment. His motivations, while rooted in a twisted ideology of Southern nationalism and white supremacy, also seem to have been fueled by a desperate desire for lasting fame, a desire to surpass his illustrious brother Edwin, and to cast himself as a historical figure on par with the Roman Brutus. He sought to be a tragic hero, but instead became an eternal villain.

In his final, desperate diary entries, Booth lamented, "I am hunted like a dog through swamps, woods, and fields; and yet I am not guilty of a crime." History, however, has rendered a different verdict. John Wilkes Booth remains a chilling reminder of how radical ideology, personal ambition, and a profound misunderstanding of the currents of history can converge in a single, destructive act, leaving an indelible scar on the soul of a nation. His shadow, cast from the stage of Ford’s Theatre, continues to serve as a dark cautionary tale in the ongoing drama of American democracy.