The Shadow on the Turnpike: Unmasking the Lone Highwayman’s Enduring Myth

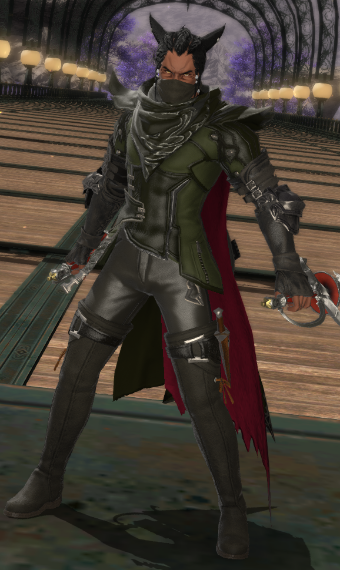

The wind howls a mournful tune, carrying with it the scent of damp earth and distant, unseen dangers. A lone stagecoach, its lamps casting flickering shadows, rumbles along a desolate turnpike, its occupants huddled in nervous silence. Suddenly, a figure emerges from the swirling mists – a dark silhouette astride a powerful steed, a mask obscuring his features, a pistol glinting in the faint light. "Stand and Deliver!" he cries, his voice a chilling command that echoes through the night.

This is the quintessential image of the lone highwayman, a figure who has galloped through centuries of folklore, literature, and popular imagination. From the dashing Claude Duval to the notorious Dick Turpin, these outlaws of the road have captured our collective fancy, embodying a blend of daring defiance, romantic rebellion, and a touch of the tragic hero. Yet, like many historical archetypes, the reality of the highwayman was often far grimmer, more desperate, and less glamorous than the legends suggest.

The "Golden Age" of the highwayman largely spanned from the late 17th to the early 19th centuries, a period characterized by burgeoning trade, poor road infrastructure, and a nascent, often ineffective, system of law enforcement. As commerce grew, so did the movement of wealth – in cash, jewels, and goods – along the ever-expanding network of turnpike roads. These roads, while facilitating travel, also created isolated stretches perfect for ambush, especially after dark. The lack of organized police forces, beyond parish constables and the occasional military patrol, meant that the chances of being caught were relatively low, and the rewards potentially high.

The Romantic Ideal vs. The Gritty Reality

The popular perception of the highwayman is steeped in romanticism. He is often depicted as a gentleman bandit, forced into a life of crime by cruel fate or social injustice. He is chivalrous, never harming women, perhaps even dancing with a noble lady before robbing her husband. He is a master of disguise, a swift rider, and an expert shot, always one step ahead of the law. This image owes much to the penny dreadfuls, ballads, and novels that flourished in later centuries, embellishing the lives of real figures and creating entirely fictional ones.

Take, for instance, Claude Duval (1643–1670), a French émigré who became one of England’s most celebrated highwaymen. His legend paints him as a suave, debonair figure, famous for his politeness and charm. One popular tale recounts him stopping a coach, and upon finding a lady with no money, he gallantly asked her to dance with him on the heath. After the dance, he allowed them to proceed, taking nothing. Such stories, while charming, likely served to soften the harsh edges of a man who, at his core, was a thief who used intimidation and the threat of violence to achieve his ends. Duval was eventually captured and, despite appeals for clemency from many society women who admired his style, was hanged at Tyburn, a testament to the brutal justice of the era.

Then there is Dick Turpin (1705–1739), arguably the most famous English highwayman. His legend is inextricably linked with his magnificent black mare, Black Bess, and a mythical ride from London to York in a single night – a feat of endurance that, in reality, was accomplished by another highwayman, "Swift Nick" Nevison, almost 50 years earlier. Turpin, in truth, was a far more brutal character. He began his criminal career as a butcher, then joined a notorious gang of deer poachers and house breakers, often resorting to torture to extract information about hidden valuables. His transition to highway robbery was more a matter of convenience and desperation than any romantic ideal. He was eventually caught and hanged for horse theft, a capital crime, not highway robbery, his notoriety solidified more by the embellished tales of authors like William Harrison Ainsworth in his 1834 novel "Rookwood."

The reality for most highwaymen was a life of fleeting riches, constant paranoia, and an almost inevitable, gruesome end. They were often desperate men, driven by poverty, gambling debts, or a simple thirst for easy money. Their victims, while sometimes wealthy, were just as often ordinary travelers, merchants, or mail carriers. The encounters were rarely the polite "Stand and Deliver!" of legend. More often, they were terrifying confrontations involving crude threats, physical violence, and the very real possibility of death for the victim, or capture and execution for the robber.

The Modus Operandi and Tools of the Trade

The highwayman’s success relied on a combination of surprise, intimidation, and speed. Their chosen hunting grounds were usually isolated stretches of road, particularly near turnpike gates where coaches might slow, or at the approaches to towns. Ambushes often occurred at dusk or dawn, or during the dead of night, when visibility was poor.

The iconic phrase, "Stand and Deliver!" was not just a dramatic flourish; it was a clear command to halt and surrender valuables. The highwayman would typically be armed with a pistol, often a large-calibre "horse pistol," which, while not always accurate, was a potent psychological weapon. The flash and report of a pistol could instill terror and ensure compliance. Many highwaymen carried multiple loaded pistols, as reloading a single-shot firearm in a hurry was impractical.

The mask, another defining feature, served the dual purpose of concealing identity and adding to the menacing aura. A simple bandana or a more elaborate cloth mask was enough to hide features, making later identification difficult, especially in poor light.

Perhaps the most crucial tool of the highwayman was his horse. A swift, strong, and intelligent mount was essential for both pursuit and escape. Highwaymen often paid exorbitant sums for their horses, understanding that their lives depended on their steed’s speed and endurance. The legendary Black Bess, whether ridden by Turpin or another, symbolizes this vital partnership between outlaw and animal.

The High Stakes: Victims and Justice

For the victims, an encounter with a highwayman was a terrifying ordeal. Beyond the loss of valuables, there was the genuine fear for one’s life. While some highwaymen might have been "gentlemanly," many were not. Stories abound of travelers being beaten, stripped, or even murdered for resisting or simply for not having enough to surrender. The psychological impact of such an encounter could last a lifetime. The sheer vulnerability of travelers on the open road contributed to the highwayman’s power and fear factor.

The law, while slow, was merciless. Highway robbery was a capital offence, punishable by death. When a highwayman was caught, the path to the gallows was often swift and brutal. Trials were summary, and convictions frequent. Public executions, particularly at London’s Tyburn Tree, were morbid spectacles, drawing vast crowds. These events served as a grim warning to aspiring criminals and a form of public entertainment. The bodies of executed highwaymen were sometimes displayed in gibbets along the roadside, a macabre monument to the consequences of their chosen profession.

Yet, even in death, some highwaymen retained a degree of notoriety, and occasionally, a perverse admiration. The crowd at Tyburn often cheered for a particularly "dashing" or defiant highwayman, seeing in him a reflection of their own struggles against authority or a vicarious thrill of rebellion.

The Decline of an Era

The age of the highwayman began to wane in the early 19th century. Several factors contributed to their decline:

- Improved Roads: Better-maintained roads and more frequent traffic made ambushes harder to execute and escape routes more limited.

- Organized Policing: The establishment of more effective law enforcement bodies, such as the Bow Street Runners in London and later the Metropolitan Police Force, significantly increased the chances of capture. These forces utilized better intelligence, faster response times, and more systematic patrols.

- Banking and Paper Money: The increasing use of banknotes, bills of exchange, and banking systems meant that fewer large sums of cash were being transported physically, reducing the potential rewards for highway robbery.

- Enclosure Acts and Urbanization: As rural areas became more populated and less wild, the isolated stretches favored by highwaymen diminished.

By the mid-19th century, the lone highwayman was largely a figure of the past, replaced by different forms of urban crime.

The Enduring Legacy

Despite their often brutal reality, the highwayman’s legend has endured, evolving from feared criminal to romantic icon. They represent a primal narrative: the individual against the system, the daring rogue living by his own rules, the shadow figure who preys on the wealthy. This archetypal appeal has been a rich source for artists, writers, and filmmakers. From John Gay’s "The Beggar’s Opera" to Alfred Noyes’s poem "The Highwayman," and countless adventure novels and films, the masked rider continues to gallop through our cultural landscape.

In a world increasingly structured and regulated, the lone highwayman offers a glimpse into a time when the boundaries between civilization and wilderness were more blurred, and individual audacity, however criminal, could carve a legend. He remains a powerful symbol of defiance, fear, and the enduring human fascination with those who live – and die – outside the law, forever casting a long, romantic shadow on the turnpikes of history.