The Shadow on the White River: How a Washington Battle Became an American Legend

America, a nation forged in paradox, is a land rich with legends. Beyond the tall tales of Paul Bunyan or the spectral whispers of colonial ghosts, there exists another category of American legend: those born from the crucible of history itself. These are not fables of mythic beasts, but the enduring, often painful, narratives of real events that have transcended mere fact to become potent symbols, shaping identity and memory. One such profound and haunting legend is etched into the very landscape of Washington State: the White River Battle, a chapter of the Puget Sound War that continues to resonate with a complex tapestry of heroism, injustice, and an enduring quest for truth.

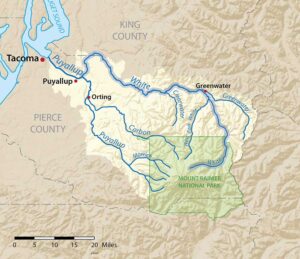

The White River Battle is less a single, decisive engagement and more a series of brutal skirmishes, retaliatory strikes, and the tragic unraveling of peace in the mid-19th century. To understand its legendary status, one must first grasp the volatile environment in which it erupted. The 1850s saw a torrent of American settlers pouring into the newly established Washington Territory, driven by the fervent ideology of Manifest Destiny and the promise of fertile lands. This westward expansion inevitably clashed with the ancient sovereignty of the region’s Indigenous peoples – the Nisqually, Puyallup, Muckleshoot, Klickitat, and others – whose lives and lands were intrinsically linked to the rivers and forests of the Puget Sound.

The Seeds of Conflict: Treaties and Tensions

At the heart of the escalating tensions was Territorial Governor Isaac Stevens, a man of relentless ambition who sought to quickly "treaty" away vast tracts of Native land to facilitate settlement. His methods were often coercive, and the resulting treaties, signed in 1854-1855, were deeply flawed, frequently misunderstood by the tribal signatories, and ultimately disastrous for Native communities. They relegated tribes to small, often unproductive reservations, severing their access to traditional hunting and fishing grounds crucial for their survival and cultural identity.

"The treaties were signed under duress, with language barriers and vastly different understandings of land ownership," explains historian Alexandra Harmon in her work on the Puget Sound War. "For the tribes, it was about coexistence and shared resources; for the Americans, it was about outright ownership and removal." This fundamental disconnect laid the groundwork for conflict. Resentment simmered, especially among leaders like Chief Leschi of the Nisqually, who saw the treaties as a betrayal and a death knell for his people’s way of life.

The Spark: October 1855

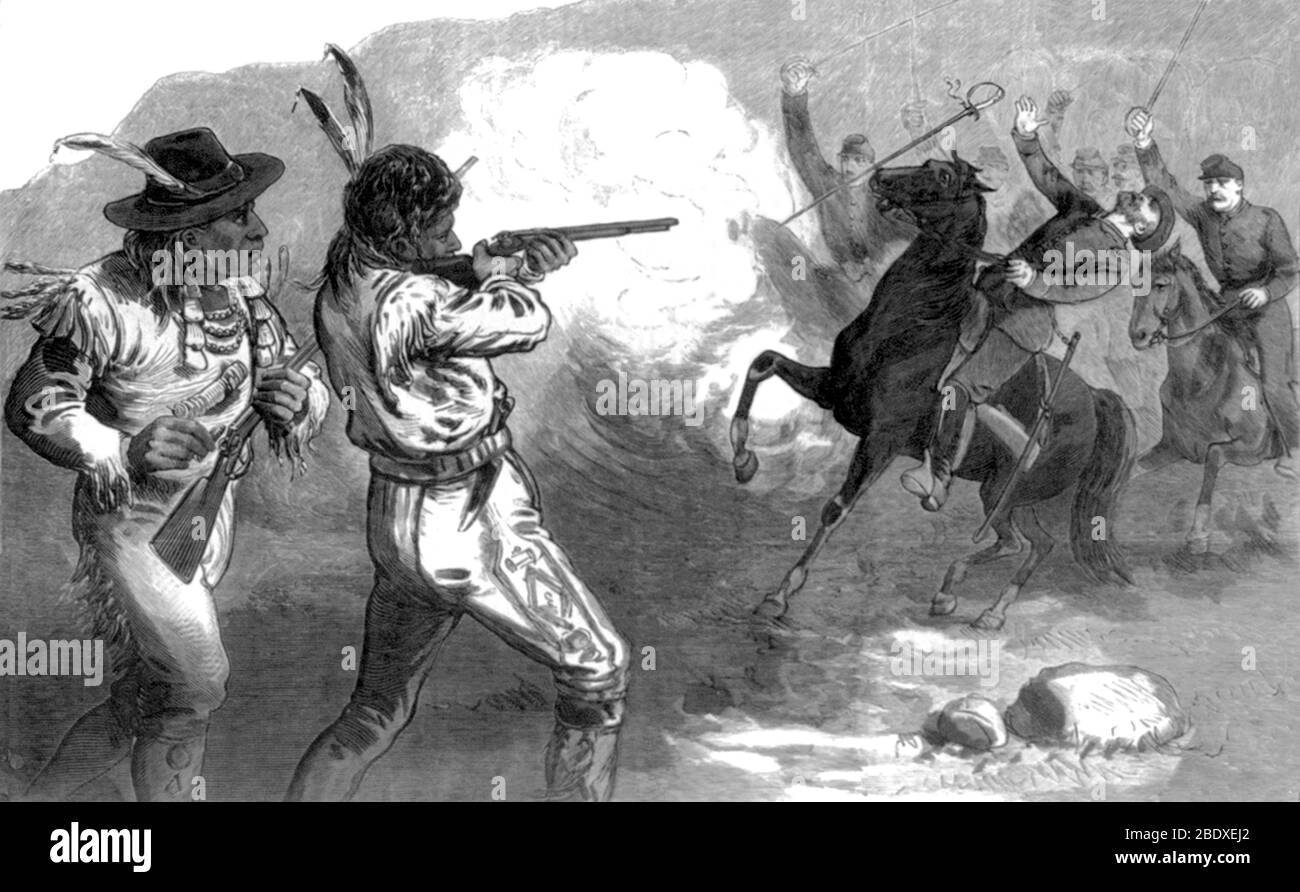

The White River Battle, as it is remembered, truly ignited in October 1855. On October 28th, a group of Native warriors, including elements from the Muckleshoot, Klickitat, and perhaps others, attacked settler families along the White River, about 25 miles southeast of Seattle. The horrific incident resulted in the deaths of nine settlers, including women and children, notably the Eaton and Fanjoy families.

News of the "White River Massacre," as it was immediately dubbed by the terrified settler population, sent shockwaves through the territory. Fear quickly morphed into outrage and a desperate call for retribution. Settlers fled to makeshift blockhouses and fortified settlements, while Governor Stevens declared martial law and mobilized volunteer militias, alongside regular U.S. Army troops from Fort Steilacoom. The Puget Sound War had begun in earnest, and the White River Valley became its bloody epicenter.

The "Battle" Unfolds: A Campaign of Skirmishes

What followed was not a single, grand battle, but a protracted and brutal campaign of skirmishes, ambushes, and retaliatory actions that stretched throughout the autumn and winter of 1855-1856. The Native warriors, led by figures like Chief Leschi and Chief Owhi, often employed effective guerrilla tactics, using their intimate knowledge of the densely forested terrain to their advantage. They struck supply lines, ambushed patrols, and disappeared into the wilderness, frustrating the better-armed but less mobile American forces.

U.S. Army regulars, under commanders like Major Granville O. Haller and Captain Maurice Maloney, along with numerous volunteer companies, scoured the White River and Puyallup valleys. Their objectives were clear: to protect settlers, punish those responsible for the attacks, and ultimately force the tribes onto their assigned reservations. This often meant burning Native villages, destroying food caches, and engaging in pitched gun battles in the dense undergrowth.

One notable engagement occurred in March 1856, near present-day Auburn, where American forces clashed with a substantial group of Native warriors. While the Americans claimed victory, driving the warriors from the field, these encounters were often costly and rarely decisive. The war was a grinding, brutal affair for both sides, marked by immense suffering. Native families, caught between the fighting, faced starvation, exposure, and the constant threat of violence.

The Tragic Figure of Chief Leschi

No figure is more central to the legend of the White River Battle than Chief Leschi of the Nisqually. Leschi had been a signatory to one of Stevens’ treaties, but he vehemently protested its terms, particularly the relocation of his people from their traditional lands to a small, arid reservation. When the war broke out, Leschi was accused by Governor Stevens and many settlers of instigating the White River attacks and leading the war effort.

Leschi, however, consistently maintained his innocence regarding the murders of the settlers on the White River, claiming he was actively trying to de-escalate tensions and protect his people. He argued that he was fighting a defensive war for his ancestral lands, not engaging in wanton murder. Despite this, he was relentlessly pursued, eventually captured through betrayal, and put on trial in 1857.

His first trial resulted in a hung jury, with some jurors convinced of his innocence, thanks in part to the powerful defense mounted by his lawyer, Elwood Evans, and the testimony of individuals who doubted his involvement in the specific killings. However, a second trial, held in a more politically charged atmosphere, quickly convicted him of murder. On February 19, 1858, Chief Leschi was hanged near Fort Steilacoom. His last words, according to historical accounts, were a defiant assertion of his innocence: "I am innocent of the charge. I did not kill the white people."

From History to Legend: Leschi’s Exoneration and Enduring Memory

Leschi’s execution immediately cemented his place in the annals of injustice. For many, particularly within the Native American community, he became a martyr, a symbol of the profound betrayal and oppression faced by Indigenous peoples during the era of westward expansion. His story was passed down through generations, an oral history interwoven with the pain and resilience of those who survived the war.

The legend of Leschi and the White River Battle gained a new, powerful dimension in the 21st century. In 2004, a historical court of inquiry, convened by the State of Washington, posthumously exonerated Chief Leschi. This unprecedented event, composed of current and retired state Supreme Court justices and tribal judges, concluded that Leschi had been wrongfully convicted and executed. They found that he was a prisoner of war, fighting for his people’s land, and that the evidence against him for the specific murders at White River was insufficient and questionable.

This exoneration was a monumental act of reconciliation, acknowledging a historical wrong and validating the long-held beliefs of Native communities. "It was a moment of healing, a recognition of truth that had been denied for far too long," stated Nisqually Tribal Chairman David Z. Iyall at the time. It shifted the narrative of the White River Battle from a simple tale of settler victory over "savage" natives to a complex story of land, sovereignty, and the tragic consequences of imperial expansion.

Today, the White River Valley, once a battleground, is a place of memory and ongoing significance. Historical markers, tribal cultural centers, and the very names of places serve as constant reminders of the conflict. The legend of the White River Battle, particularly through the lens of Chief Leschi, challenges simplistic historical narratives. It compels us to confront the darker aspects of American history, to understand the profound and lasting impact of colonization on Indigenous peoples, and to recognize the enduring strength and resilience of Native cultures.

The White River Battle is not a static legend; it is a living narrative that continues to evolve as new perspectives emerge and as society grapples with its past. It stands as a powerful testament to the fact that some of America’s most potent legends are not found in the realm of fantasy, but in the heart of its complicated, often tragic, history—a history that demands to be remembered, understood, and continually re-evaluated in the pursuit of a more just future.