The Shadowed Echoes of Neches: A Legend Forged in Blood and Betrayal

America’s tapestry of legends is woven with threads of diverse hues – the towering figures of frontier folklore, the spectral whispers of colonial haunts, and the epic narratives of exploration and expansion. Yet, beneath the vibrant patterns of heroic myths, lie darker, more somber legends, born not of triumphant conquest but of profound loss, broken promises, and the enduring resilience of the dispossessed. Among these, etched into the collective memory of the Cherokee Nation and the annals of Texas history, is the poignant and often overlooked legend of the Battle of Neches. It is a story not of a fantastical creature or a superhuman feat, but of a real and tragic conflict that forever altered the destiny of a people, a legend that speaks to the very heart of America’s complex relationship with its indigenous inhabitants.

The Cherokee, a people renowned for their sophisticated governance, written language, and agricultural prowess, had already endured unimaginable suffering by the time their weary footsteps led them to the vast, untamed lands of what would become the Republic of Texas. Driven from their ancestral homes in the southeastern United States by the relentless pressures of westward expansion and the infamous Indian Removal Act of 1830, they had sought refuge, a final sanctuary, far from the reach of a government that had repeatedly betrayed their trust. Many had walked the harrowing "Trail of Tears," a forced migration that claimed thousands of lives, leaving an indelible scar on the soul of the Nation.

By the 1820s and 1830s, several bands of Cherokee, along with other displaced tribes like the Shawnee and Delaware, had established communities along the fertile river bottoms of East Texas. Here, under the leadership of venerated chiefs such as Duwali, known to Texans as Chief Bowles, they sought to rebuild their lives. Bowles, a man of mixed Scottish and Cherokee heritage, was a seasoned diplomat and a respected elder, whose very presence exuded a quiet dignity. He sought peace and stability for his people, envisioning a future where they could live unmolested on their chosen lands.

Their claims to these lands were not without basis. In 1836, as Texas fought for its independence from Mexico, the interim government, led by Sam Houston – a man who had lived among the Cherokee and held a deep respect for them – signed a treaty with Chief Bowles. This landmark agreement, known as the "Bowles Treaty" or "Treaty of Bowles Village," explicitly recognized the Cherokee’s right to their lands in East Texas, provided they remained neutral during the Texas Revolution. For Bowles and his people, this treaty was a beacon of hope, a solemn promise of a permanent home. It was, as historian Gary Clayton Anderson notes in "The Conquest of Texas," a moment where "Houston, in his desperate hour, pledged away land he did not fully possess, but it was a pledge the Cherokee took seriously."

However, the ink on that treaty was barely dry before the political winds in the nascent Republic of Texas shifted dramatically. Sam Houston’s presidency was followed by that of Mirabeau B. Lamar in 1838. Lamar, a fierce nationalist and an ardent proponent of Anglo-American expansion, held a radically different view of Native Americans. He famously declared that the "Cherokee, Shawnee, and other tribes…must be removed, or exterminated." His policy was clear, uncompromising, and utterly devoid of the empathy that had characterized Houston’s approach. Lamar saw the Cherokee not as a sovereign people with legitimate claims, but as an impediment to Texas’s destiny, a foreign element occupying valuable land.

The pretext for their removal soon materialized. In 1838, a Mexican-instigated rebellion among some Tejano and Native American groups, known as the Cordova Rebellion, erupted in East Texas. Though the Cherokee under Chief Bowles remained largely neutral, actively discouraging their young men from joining the uprising, Lamar seized upon the incident as "proof" of Cherokee disloyalty and collusion with Mexico. This accusation, largely unfounded in the case of Bowles’ band, served as a convenient justification for abrogating the 1836 treaty and implementing Lamar’s aggressive removal policy.

The stage was set for an inevitable, tragic confrontation. In the spring of 1839, Lamar sent commissioners to the Cherokee with an ultimatum: either accept a monetary payment for their improvements and peacefully relocate north of the Red River, or face forced removal by military might. Chief Bowles, an old man of nearly 80, was devastated but resolute. He knew the futility of armed resistance against the numerically superior Texan forces, but he also knew the immense sacrifice his people had made to reach these lands. He tried to negotiate, to appeal to the honor of the treaty, but Lamar’s administration was unyielding. The Cherokee were given a deadline: leave by July 16, 1839.

As the deadline approached, the Cherokee, under Bowles’ leadership, began to slowly move north, hoping to buy time and perhaps negotiate a better outcome. They were accompanied by a detachment of Texan troops, ostensibly to ensure their safe conduct. However, this escort soon turned into an armed escort, pressing the Cherokee further, preventing them from scattering, and effectively herding them towards a pre-determined fate.

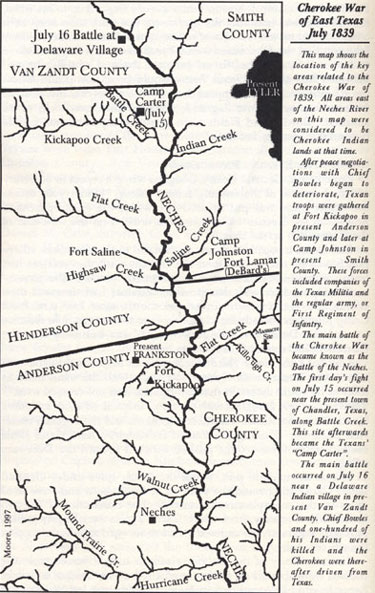

On July 15, 1839, near the Neches River, a skirmish broke out. Texan forces, numbering around 500-600 men under the command of General Kelsey H. Douglass, intercepted the moving Cherokee column, which comprised approximately 500 warriors, along with women, children, and their possessions. The Texans demanded the Cherokee surrender their weapons. Chief Bowles, knowing this would leave his people defenseless, refused. A brief but intense exchange of fire ensued. The Cherokee, outgunned and outnumbered, fought valiantly, but were forced to retreat.

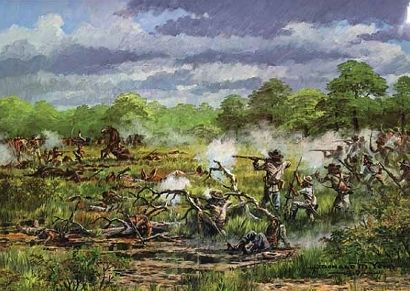

The main engagement, the Battle of Neches, occurred the following day, July 16, 1839. The Cherokee, having strategically positioned themselves in a dense thicket near the Neches River, prepared for their final stand. Chief Bowles, despite his advanced age, dressed in his finest attire – a turban, a sash, and a silver gorget, armed with the sword given to him by Sam Houston – rode out to rally his warriors. He knew the odds were against them, but surrender was not an option for a man who had dedicated his life to securing a home for his people.

The Texan forces, comprised of regular army troops, militia, and volunteers, launched a frontal assault. The battle was fierce and chaotic, fought amidst the dense undergrowth and towering trees. The Cherokee, masters of woodland warfare, fought with desperate courage, inflicting casualties on the advancing Texans. For over an hour, the woods echoed with the crack of muskets, the war cries of the Cherokee, and the shouts of the Texans.

However, the sheer numerical and technological superiority of the Texans eventually began to tell. As the Cherokee lines faltered, Chief Bowles, wounded by a musket ball, was still mounted on his horse. According to accounts from both Texan and Cherokee sources, he was then shot in the head at close range by a Texan soldier, Private Henry Conner, who later reportedly scalped him. Other accounts suggest he was first wounded, dismounted, and then shot while sitting on the ground, defiant to the last. His death marked the symbolic end of the Cherokee’s organized resistance in Texas.

The battle concluded with a decisive Texan victory. Approximately 100 Cherokee warriors, women, and children were killed, while Texan casualties were remarkably light, with only three killed and five wounded. The remaining Cherokee survivors, shattered and heartbroken, scattered into the wilderness, some eventually making their way to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma), others disappearing into the vastness of the continent, forever displaced from their Texas homes. The Texan troops proceeded to burn their villages, destroy their crops, and confiscate their livestock, eradicating any trace of the Cherokee presence.

The legend of Neches endures not as a tale of glorious triumph for the Texans, but as a profound and sorrowful narrative of injustice for the Cherokee. It is a legend whispered through generations of a people who lost their land, their peace, and their respected leader, all due to the broken word of a burgeoning nation. It speaks of the futility of treaties when faced with unbridled expansionism, and the devastating cost of a policy driven by greed and prejudice.

Today, historical markers stand near the battle site in Henderson County, Texas, commemorating the event. While the Texan markers often emphasize the military victory, the Cherokee descendants and historians remember Neches as a tragic last stand, a testament to Chief Bowles’ unwavering courage and his people’s enduring spirit in the face of insurmountable odds. The battle marked the effective end of the Cherokee presence in Texas, pushing them further into exile, adding another chapter to their long history of displacement and resilience.

In the broader context of "Legends of America," the Battle of Neches serves as a crucial counter-narrative. It challenges the often-romanticized frontier mythology of brave settlers conquering a wild land, reminding us that for every tale of triumphant expansion, there is a corresponding story of dispossession and profound loss. It is a legend that compels us to confront the uncomfortable truths of our nation’s past, to acknowledge the sacrifices made by those who stood in the path of "progress," and to remember that the spirit of a people, though broken, can never be truly extinguished. The shadowed echoes of Neches, the last stand of Chief Bowles and his people, serve as a timeless reminder that some legends are not about heroes and villains, but about the enduring human cost of empire, and the sacred, often-unfulfilled, promise of a home.