The Shimmering Echo of a Dream: Preserving Grandma Prisbrey’s Bottle Village

Nestled amidst the unassuming suburban sprawl of Simi Valley, California, lies a place where the mundane transmutes into the magnificent, where discarded glass bottles catch the sunlight in a kaleidoscopic dance, and the very air seems to hum with the spirit of one woman’s extraordinary vision. This is Grandma Prisbrey’s Bottle Village, a fantastical folk art environment that stands as a shimmering, fragile testament to human creativity, resilience, and the power of turning perceived junk into enduring art. It is a site that defies easy categorization, a historical landmark, an architectural marvel built by hand, and a deeply personal narrative etched in mortar and glass – a journalistic treasure trove waiting to be explored.

The story of Bottle Village begins not with an architect’s blueprint or an artist’s manifesto, but with a deeply personal epiphany experienced by Tressa "Grandma" Prisbrey, a woman in her early sixties who, by all accounts, had lived a life marked by hardship and resourcefulness. Born in 1896 in rural Iowa, Prisbrey moved to California in the mid-20th century, bringing with her the practical spirit of the pioneer and a profound connection to the objects around her.

The year was 1956, and Tressa Prisbrey had just buried her beloved daughter, a grief that settled heavily upon her. In the wake of this profound loss, a dream came to her, clear and compelling: she must build a house out of bottles. "I just got tired of seeing all those bottles thrown away," she later recounted, "and I figured I could make something out of it." This seemingly simple motivation belied a deeper, spiritual calling. The bottles, to Prisbrey, were not just refuse; they were imbued with a life force, waiting to be reborn. She believed that collecting and repurposing them would not only honor her daughter but also prevent their destruction, which she saw as a form of waste, both material and spiritual.

With no formal training in art or construction, and armed only with an unwavering determination, Tressa began her monumental task. She started by visiting the local dump, collecting discarded bottles – milk bottles, soda bottles, perfume bottles, anything she could find. Her initial goal was to collect 50,000 bottles, a number that would eventually be dwarfed by her actual output. Over the next 25 years, working daily, often alone, she would transform her modest half-acre property into a whimsical, sprawling complex of 13 structures and numerous pathways, all meticulously crafted from over 130,000 bottles and countless other found objects.

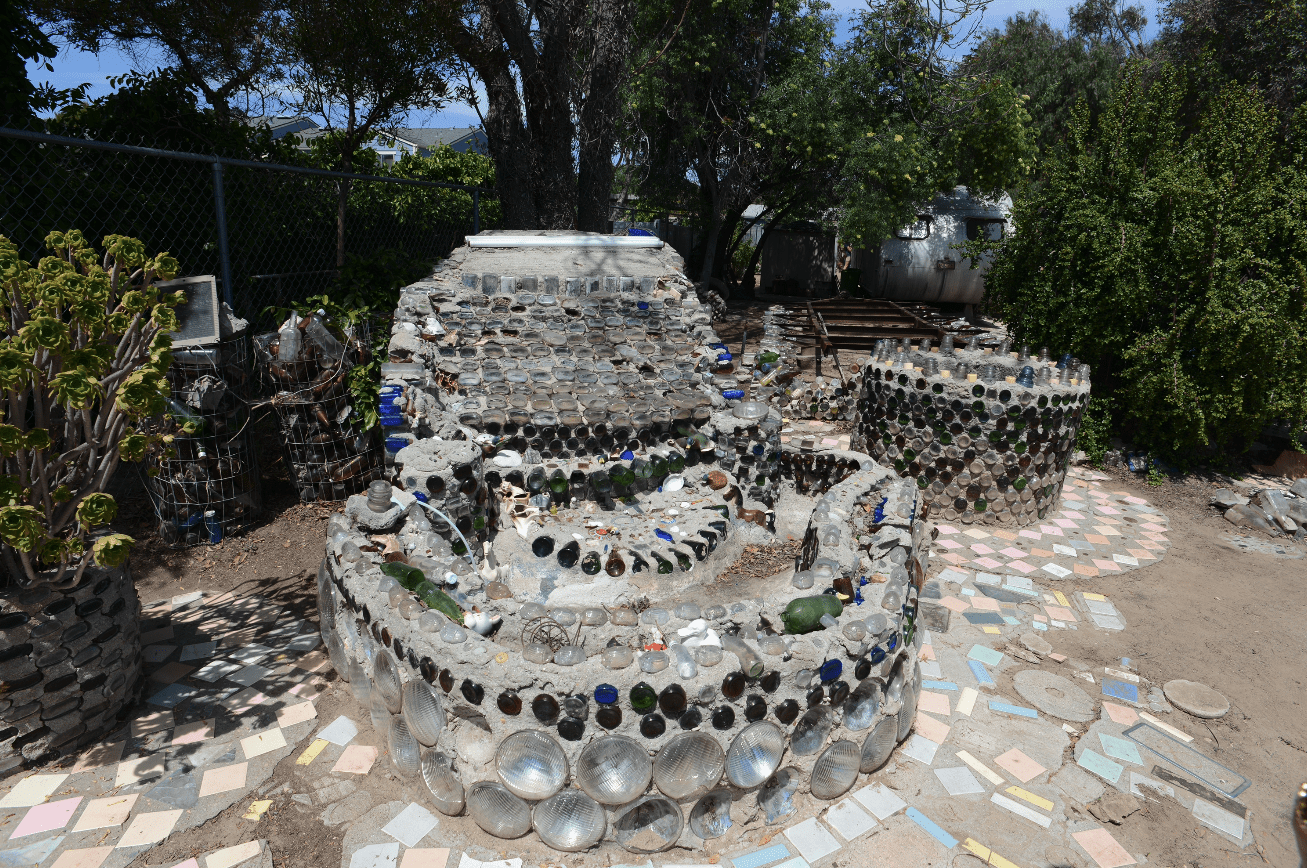

The structures themselves are a marvel of naive architecture and imaginative design. There’s the "Bottle House," her original dwelling, where the walls are a mosaic of embedded glass, allowing light to filter through in myriad hues. Then there are miniature chapels, the "Leaning Tower of Bottle Village," a "Rapunzel’s Tower," and a grand "Parthenon" – each a testament to her creative spirit. She built a wishing well, a "Doll House" filled with her vast collection of dolls and figurines, and even a "Face of a Dead Man" made from various objects. Each building has a unique character, often adorned with other discarded treasures: old radios, hubcaps, doll heads, car parts, vacuum cleaner hoses, even a toilet seat repurposed as a decorative archway.

Prisbrey’s construction technique was rudimentary yet effective. She laid out bottles with their necks pointing inward, cementing them together with mortar, creating thick, insulative walls that glowed from within when the sun hit them just right. The effect is enchanting, a cathedral of light and color, a living kaleidoscope that shifts with the day. "I always say that anyone can do anything if they want to," Prisbrey often declared, a motto that perfectly encapsulated her approach. She saw beauty and potential in everything, transforming the detritus of consumer culture into a deeply personal, spiritual landscape.

Her vision extended beyond just bottles. She was a prodigious collector, and the Village became a repository for her vast and eclectic hoard of dolls, ceramic figures, presidential memorabilia, and assorted trinkets. These collections were not merely displayed; they were integrated into the fabric of the structures, peering out from shelves or embedded in the walls, creating a dialogue between the art and the artist’s personal history. The entire village became an autobiography in three dimensions, a material manifestation of her memories, dreams, and anxieties.

Initially, Bottle Village was a local curiosity, attracting visitors from nearby towns who heard tales of the eccentric "Grandma" and her glittering houses. As word spread, however, it began to gain wider recognition, particularly within the nascent fields of folk art and outsider art. Art critics and scholars started to see it not just as a peculiar hobby, but as a significant example of self-taught art, a powerful expression untainted by formal training or commercial aspirations. It was recognized as a unique American art environment, a category of art that blurs the lines between sculpture, architecture, and landscape.

In 1979, Bottle Village was officially designated a California Historical Landmark, a significant achievement for a site created by an untrained artist from discarded materials. This was followed by its listing on the National Register of Historic Places in 1993, solidifying its place as a nationally recognized cultural treasure. These designations not only brought prestige but also offered a layer of protection, crucial for a site so inherently fragile.

Tressa Prisbrey continued to work on her Village until her health began to decline in the mid-1980s. She passed away in 1988 at the age of 92, leaving behind a legacy that captivated and inspired. However, her passing also marked the beginning of a new chapter for Bottle Village – one of struggle, preservation, and the dedicated efforts of a community determined to keep her dream alive.

The greatest challenge came on January 17, 1994, with the devastating Northridge Earthquake. Measuring 6.7 on the Richter scale, the quake wreaked havoc across Southern California, and Bottle Village, with its delicate, mortar-and-glass construction, was particularly vulnerable. Many structures were severely damaged, some collapsing entirely. The "Leaning Tower of Bottle Village" leaned precariously close to total ruin, and large sections of walls crumbled. The site looked like a war zone, and for a time, demolition seemed inevitable.

It was at this critical juncture that the community rallied. The Preserve Bottle Village Committee, later evolving into the Bottle Village Preservation Group, was formed by dedicated volunteers, historians, and art enthusiasts. Their mission was clear: save Grandma Prisbrey’s masterpiece. The task was monumental, requiring not just physical labor but also fundraising, historical research, and navigating complex bureaucratic hurdles. They had to stabilize the damaged structures, meticulously sort through debris, identify original materials, and plan for sensitive restoration that would honor Prisbrey’s original vision while ensuring the long-term viability of the site.

The restoration efforts have been a slow, painstaking process. Volunteers, often working in sweltering heat, have spent countless hours carefully rebuilding walls, mending broken structures, and cataloging the thousands of artifacts that make up the Village. The group has secured grants from various sources, including the National Trust for Historic Preservation and the Getty Conservation Institute, but funding remains an ongoing challenge. The materials themselves – bottles, mortar, and other found objects – are susceptible to weather, vandalism, and the simple passage of time.

Today, Bottle Village is not fully open to the public in the way it once was during Prisbrey’s lifetime, when she would personally give tours to visitors, sharing her stories and insights. Access is often limited to special events and guided tours, primarily to protect the ongoing restoration work and the delicate nature of the site. Yet, even in its partially restored state, the magic persists. Visitors who are fortunate enough to step onto the grounds are transported to another realm, where the past whispers through the shimmering glass, and the indomitable spirit of Tressa Prisbrey feels remarkably present.

The significance of Bottle Village extends far beyond its aesthetic appeal or historical designation. It is a powerful symbol of early recycling and repurposing, predating modern environmental movements by decades. Prisbrey’s ethos of "I never throw anything away, I save it" was a radical act of sustainability, demonstrating how beauty and utility can emerge from what society deems waste. It challenges conventional notions of art, architecture, and value, proving that the most profound expressions can come from the most unexpected sources and materials.

Furthermore, Bottle Village serves as a poignant reminder of the power of individual vision and the human need for creative expression, especially in the face of adversity. Prisbrey transformed her grief into a productive, joyful act of creation, building a personal sanctuary that ultimately became a public treasure. Her story inspires countless individuals to look at their surroundings with new eyes, to find beauty in the discarded, and to pursue their passions regardless of perceived limitations.

In a world increasingly dominated by mass production and digital experiences, Grandma Prisbrey’s Bottle Village stands as a vital counterpoint: a tangible, handmade, deeply personal space that speaks to the enduring human desire to leave a mark, to create meaning, and to find wonder in the everyday. It is a shimmering echo of a dream, a testament to one woman’s unwavering spirit, and a fragile masterpiece that continues to inspire awe and spark the imagination, ensuring that the legacy of Simi Valley’s extraordinary bottle builder will glow for generations to come. To visit is to step into a poem, written in glass and light, by a woman who truly built her own world, one bottle at a time.