The Silent Artery: Fort Leavenworth-Fort Gibson Military Road, A Vein of Manifest Destiny

Stretching across the vast, untamed expanse of the American frontier in the early 19th century, a vital artery pulsed with the ambitions, fears, and relentless drive of a young nation. It wasn’t a paved highway, but a cleared trace, a formidable path hewn from prairie and forest: the Fort Leavenworth-Fort Gibson Military Road. This forgotten thoroughfare, connecting two crucial outposts of the U.S. Army, was far more than a logistical route; it was a physical manifestation of Manifest Destiny, a conduit for westward expansion, a tool of both protection and displacement, and a silent witness to a pivotal era in American history.

The story of the military road begins with the strategic necessity of establishing order and projecting power in the newly acquired territories following the Louisiana Purchase of 1803. By the 1820s and 1830s, the concept of a "Permanent Indian Frontier" was taking shape, a demarcation line intended to separate white settlement from the lands designated for relocated Native American tribes, particularly those forcibly removed from the southeastern United States. To enforce this, and to protect both settlers and the relocated tribes from perceived threats and internal conflicts, a chain of military forts was deemed essential.

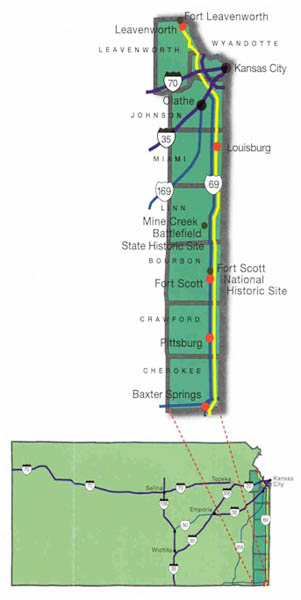

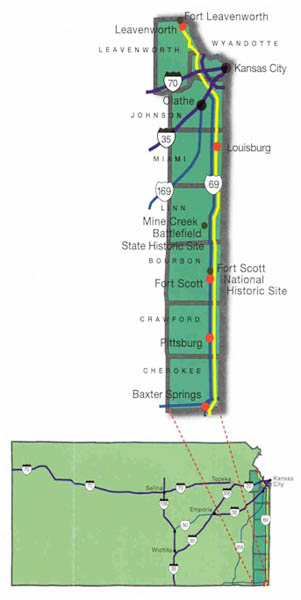

Fort Leavenworth, established in 1827 on the west bank of the Missouri River in what is now Kansas, and Fort Gibson, founded in 1824 near the confluence of the Grand, Verdigris, and Arkansas Rivers in present-day Oklahoma, were two critical anchors in this defensive chain. Leavenworth, situated at a major river crossing, was the northernmost outpost and a primary staging ground for western expeditions. Gibson, deep within the Indian Territory, served as a crucial point of contact and control for the Cherokee, Creek, Choctaw, Chickasaw, and Seminole nations being resettled there.

The vast distance between these two forts, approximately 250 miles, presented a significant logistical challenge. Communication was slow, troop movements arduous, and supplies precarious. The need for a direct, reliable connection became paramount. Thus, in the early 1830s, the U.S. Congress authorized the construction of a military road. This wasn’t a project undertaken by civilian contractors with heavy machinery; it was a grueling task assigned to the very soldiers who would later patrol its length, often augmented by hired civilian laborers and even enslaved individuals.

The construction itself was an epic undertaking. Imagine the scene: platoons of soldiers, axes in hand, hacking through dense timber, clearing underbrush, leveling uneven ground, and bridging countless streams and rivers. The path was not simply a straight line; it had to navigate treacherous terrain, avoid impassable swamps, and find the most practical crossings. The route generally followed a south-southwesterly direction, tracing the natural contours of the land. It passed through the tallgrass prairies of what would become eastern Kansas, skirted the rugged Ozark foothills, and eventually descended into the river valleys of northeastern Oklahoma.

Disease, particularly malaria and cholera, was a constant threat, claiming more lives than any skirmish. Supplies were often scarce, and the sheer physical exertion under the unforgiving prairie sun or through bitter winter winds tested the limits of endurance. Yet, slowly, painstakingly, the "road" took shape – not a macadamized highway, but a cleared trace wide enough for wagons and troop formations, marked by blazes on trees and occasional stone cairns.

The primary purpose of the Fort Leavenworth-Fort Gibson Military Road was multifaceted. Firstly, it served as a critical supply route. Wagons laden with food, ammunition, clothing, and equipment for the isolated garrisons at both forts and intermediate posts like Fort Scott, which would later be established along its path, lumbered along its length. Without this lifeline, the forts would have been untenable.

Secondly, and perhaps most importantly, it was a corridor for military movement. Troops could be dispatched rapidly – or at least more rapidly than before – to quell perceived Native American hostilities, enforce treaties, or escort removal parties. The road was instrumental in projecting federal authority into the heart of the Indian Territory. As historian William E. Foley noted regarding the broader network of military roads, "They facilitated the government’s ability to regulate trade, enforce peace, and oversee the often-controversial policy of Indian removal."

Indeed, the road played a somber role in the tragic history of the Trail of Tears. While many of the forced marches of the Cherokee and other southeastern tribes took different routes, the existence of the military road and the forts it connected provided the logistical backbone for the entire removal policy. It allowed for the deployment of troops to round up and escort tribes, and to maintain order (or control) in the newly established Indian Territory. The road, for many Native Americans, symbolized the relentless encroachment of the United States government and the loss of their ancestral lands.

Beyond its military utility, the road also facilitated exploration and communication. Mail couriers risked life and limb to carry dispatches between the forts, keeping the remote outposts connected to the broader network of the U.S. Army and the federal government. Exploratory expeditions, often launched from Fort Leavenworth, utilized sections of the road as their initial departure points, venturing further into the unmapped western territories.

One of the most famous episodes associated with the road was the Dragoon Expedition of 1834. Launched from Fort Gibson, this massive military maneuver, initially led by General Henry Leavenworth (after whom Fort Leavenworth was named) and later by Colonel Henry Dodge, aimed to impress the Comanche, Kiowa, and Wichita tribes with American military power and establish diplomatic relations. The expedition, which included hundreds of mounted dragoons, traversed significant portions of the military road before venturing deeper into the plains.

A particularly fascinating aspect of the Dragoon Expedition was the inclusion of Washington Irving, the celebrated author of "Rip Van Winkle" and "The Legend of Sleepy Hollow." Irving, seeking new inspiration, accompanied the expedition and later chronicled his experiences in his vivid travelogue, A Tour on the Prairies (1835). His observations provide invaluable insights into the landscape, the military life, and the Native American cultures of the time. Describing the military’s presence, Irving noted the soldiers’ stoicism: "These hardy fellows were built for the rough life of the frontier, accustomed to privation, and ready to face any hardship with a grim sort of humor." His writings humanize the frontier experience, even as they reflect the prevailing attitudes of the era.

The military road also had an indirect but significant impact on civilian settlement and trade. While primarily a military thoroughfare, its cleared path inevitably attracted traders, trappers, and early settlers. Waypoints along the road often grew into trading posts, and some of these eventually blossomed into towns. It created a corridor, however rudimentary, that linked the nascent settlements of Missouri with the deeper interior, facilitating the movement of goods and people and contributing to the gradual "filling in" of the frontier. The road thus served as a precursor to later, more famous routes like the Santa Fe Trail, intersecting and sometimes overlapping with them.

However, like many frontier arteries, the Fort Leavenworth-Fort Gibson Military Road eventually faded into obsolescence. The relentless march of progress, particularly the advent of the railroad, rendered it obsolete. By the latter half of the 19th century, trains could transport troops and supplies far more quickly and efficiently than horse-drawn wagons. The Civil War briefly saw a resurgence in its use, as both Union and Confederate forces utilized parts of the old road for troop movements in the border states and Indian Territory, but this was a temporary reprieve.

As the frontier receded, and the "Indian Wars" largely concluded, the need for a dedicated military road diminished. The forts themselves evolved; Fort Leavenworth transitioned into a significant center for military education and training, while Fort Gibson eventually ceased to be an active military post. The cleared path, once meticulously maintained by soldiers, slowly succumbed to the elements, swallowed by prairie grasses and encroaching forests.

Today, little physical evidence of the original Fort Leavenworth-Fort Gibson Military Road remains. Modern highways and county roads often follow its general alignment, hinting at its forgotten path. Historical markers in Kansas and Oklahoma occasionally commemorate its existence, prompting a pause for reflection on the struggles and aspirations of those who traversed it.

Yet, its legacy endures. The Fort Leavenworth-Fort Gibson Military Road was more than just a route; it was a testament to the strategic vision of a burgeoning nation, a symbol of the immense physical and human cost of westward expansion, and a stark reminder of the complex and often contradictory forces that shaped the American frontier. It was a silent artery, pumping lifeblood into the nation’s expansionist dreams, while simultaneously facilitating the displacement and suffering of indigenous peoples. Its story is etched into the very landscape it traversed, a vital, if often overlooked, chapter in the epic narrative of American history.