The Silent Sentinel: Fort Wakarusa and Kansas’s Quiet Defense in a Bleeding Land

In the annals of the American Civil War, the names Gettysburg, Vicksburg, and Antietam echo with the thunder of cannons and the cries of men. Yet, in the heart of a state forged in fire, a different kind of heroism unfolded, often without a single shot fired in anger. This is the story of Fort Wakarusa, a humble earthwork fort in Kansas, a silent sentinel that stood guard over the promise of freedom in a land drenched in the blood of its convictions.

To understand Fort Wakarusa, one must first grasp the tumultuous crucible that was "Bleeding Kansas." Long before the first shots at Fort Sumter, Kansas was a microcosm of the national conflict, a brutal proving ground for the ideological war over slavery. The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 ignited a powder keg, allowing residents of these new territories to decide for themselves whether to permit slavery – a concept known as "popular sovereignty." This policy, intended to diffuse tension, instead sparked a localized civil war that predated the national conflict by half a decade.

A Crucible of Conflict: Bleeding Kansas

From 1854 to 1861, Kansas was a battleground where abolitionist Free-Staters and pro-slavery Border Ruffians clashed with terrifying regularity. Lawrence, a vibrant and rapidly growing town founded by the New England Emigrant Aid Company as an anti-slavery stronghold, became a particular flashpoint. It was a beacon of hope for those seeking a future free from human bondage, and thus, a constant target for pro-slavery forces emanating from neighboring Missouri.

The Sack of Lawrence in May 1856, where a pro-slavery posse ransacked the town, destroyed newspaper offices, and burned the Free-State Hotel, served as a stark warning. It underscored the vulnerability of Kansas communities and the desperate need for self-defense. This wasn’t merely about property; it was about the very soul of the territory, a struggle for the definition of American liberty.

As the national conflict escalated, and with Kansas officially admitted to the Union as a free state in January 1861, the threat from Missouri did not wane. Instead, it intensified. Missouri, a slave state, was deeply divided, with its western counties harboring fervent Confederate sympathies and a history of raiding into Kansas. The border became a fluid, violent frontier, plagued by guerrilla warfare, bushwhackers, and retaliatory raids from Kansas Jayhawkers.

The Birth of a Fort: A Community’s Resolve

It was against this backdrop of pervasive fear and relentless aggression that the citizens of Lawrence, and the surrounding Douglas County, recognized an urgent need for more robust protection. While local militias had formed, they often lacked a centralized, fortified position from which to operate and defend against large-scale incursions. The memory of the 1856 sack, and the constant threat of a repeat, hung heavy in the air.

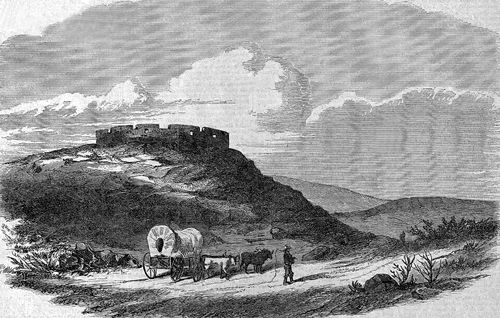

In late 1861, the decision was made to construct a permanent defensive fortification south of Lawrence. The site chosen was strategic: a rise of ground overlooking the Wakarusa River valley, a natural invasion route for forces approaching Lawrence from the south and southeast. This location allowed for observation of the river and the surrounding plains, providing an early warning system against advancing enemy columns.

Fort Wakarusa, as it came to be known, was not a grand stone fortress built by federal engineers. It was a testament to community resolve, largely constructed by the hands of local volunteers – farmers, merchants, and ordinary citizens who understood that their homes and their ideals depended on their own vigilance. They dug earthworks, felled trees for palisades and blockhouses, and toiled with a shared purpose, transforming a pastoral landscape into a bulwark against tyranny.

"This was not some distant war for us," remarked a fictionalized, yet historically representative, Kansan settler of the era. "The war was at our doorstep, across the river, just over the border. We built that fort with our own sweat because we knew if we didn’t, no one else would truly protect what we had fought so hard to build."

The fort was a roughly square or rectangular earthwork, fortified with log structures. It featured a parapet and a ditch (moat), designed to impede advancing infantry and provide cover for defenders. Cannon, likely of a smaller caliber or even repurposed agricultural machinery, would have been positioned to command the approaches. Its design was practical, reflecting the resources available and the immediate need for defense against cavalry raids and guerrilla attacks rather than prolonged siege warfare.

Life at the Fort: Vigilance and Drudgery

Life at Fort Wakarusa was a stark contrast to the dramatic battles fought elsewhere. There were no grand charges or heroic last stands within its walls. Instead, it was a routine of vigilance, training, and the monotonous drudgery of military life. Soldiers, often local militiamen or Kansas volunteers awaiting deployment to larger theaters, garrisoned the fort.

Their days would have been filled with drills – marching, handling their rifles, practicing formations. Picket duty, scouting patrols, and maintaining the fort’s defenses were constant tasks. The threat was ever-present, even if unseen. Rumors of Confederate cavalry movements, intelligence reports of bushwhacker activity, and the distant sounds of gunfire would have kept the garrison on edge.

The conditions were undoubtedly basic. Soldiers lived in tents or simple log barracks, exposed to the harsh Kansas weather – sweltering summers, frigid winters, and sudden, violent storms. Food would have been simple rations, supplemented by hunting or supplies from Lawrence. Disease, a constant companion in any Civil War encampment, would have been a pervasive threat, often claiming more lives than enemy bullets.

Yet, despite the hardship and the quiet nature of their service, the men at Fort Wakarusa understood their vital role. They were the first line of defense for Lawrence, a symbol of freedom. Their presence alone was a powerful deterrent, forcing potential attackers to either reconsider or seek more circuitous, and thus more dangerous, routes.

The Unfought Battle: A Deterrent’s Legacy

Fort Wakarusa’s most significant achievement lies not in a famous battle fought within its walls, but in the battles that were never fought because of its existence. Its strategic location and visible fortifications sent a clear message: Lawrence was prepared.

This deterrent effect was particularly crucial in a war characterized by guerrilla tactics and hit-and-run raids. Pro-slavery forces, often under the command of notorious figures like William Clarke Quantrill, preferred to strike at undefended or lightly defended targets. The presence of Fort Wakarusa on a key approach made a direct assault on Lawrence from the south a far more perilous proposition.

However, Fort Wakarusa’s presence did not make Lawrence invulnerable to all threats. The infamous Quantrill’s Raid on August 21, 1863, remains one of the darkest chapters in Kansas history. Quantrill, with a force of over 400 bushwhackers, launched a devastating attack that largely bypassed Fort Wakarusa. Approaching Lawrence from the east/northeast, his raiders swept into the sleeping town, killing nearly 200 unarmed men and boys, and burning most of the city to the ground.

The fact that Fort Wakarusa did not prevent Quantrill’s Raid has sometimes led to questions about its effectiveness. However, it’s important to note that Quantrill deliberately chose an approach that circumvented the fort’s primary line of defense. The fort was positioned to guard the southern river valley, not the entire perimeter of the town against a determined, large-scale, and strategically evasive force. Its presence still forced Quantrill to take a more circuitous route, consuming valuable time and energy, even if it ultimately proved insufficient to stop the horror that unfolded.

"While the fort could not stop every determined enemy," noted a historical account, "it certainly narrowed the avenues of attack and provided a necessary psychological anchor for the beleaguered citizens of Lawrence. Without it, the town would have been even more exposed." It served its primary purpose: to guard a specific, well-known invasion route and to deter general incursions.

Decline and Enduring Legacy

As the Civil War drew to a close in 1865, and the threat of Missouri raids diminished, the need for Fort Wakarusa faded. Like many temporary fortifications of the era, it was gradually dismantled. Its log structures were likely repurposed for civilian use, and the earthworks, left to the elements, slowly eroded and blended back into the landscape. The land eventually returned to agricultural use, its military past obscured by fields of corn and wheat.

Today, little remains of the original Fort Wakarusa. There are no imposing stone walls or preserved barracks. What endures is the subtle undulation of the land, faint traces of the earthworks that once defined its perimeter. A historical marker, placed by the Kansas Historical Society, now commemorates the site, standing as a quiet testament to the fort’s significance. It serves as a physical reminder of the vigilance and sacrifice of the Kansans who built and garrisoned it.

The story of Fort Wakarusa is a powerful reminder that not all heroism takes place on a grand battlefield. It speaks to the resilience of ordinary people, the strength of community, and the profound impact of deterrence in warfare. It symbolizes the unwavering commitment of Kansans to their Free-State ideals, even when faced with overwhelming odds and constant danger.

In an era of great national upheaval, Fort Wakarusa stood as a silent promise: a promise of defense, a promise of freedom, and a promise that Lawrence, and indeed Kansas, would not fall without a fight. Its legacy is not etched in glory, but in the quiet, resolute courage of those who stood guard, ensuring that the ideals for which "Bleeding Kansas" fought would ultimately prevail. The silent sentinel may have vanished, but its spirit of defiant self-preservation echoes through the Kansas plains to this day.