The Silent Sentinel of the Susquehanna: Fort Augusta’s Enduring Legacy on Pennsylvania’s Frontier

Where the mighty Susquehanna River, an ancient artery of commerce and conflict, splits into its West and North Branches, lies a landscape steeped in American history. Today, the bustling city of Sunbury, Pennsylvania, stands as a testament to centuries of human endeavor. Yet, beneath its modern veneer, and particularly within the quiet grounds of the Fort Augusta Museum, whispers of a more tumultuous past persist. Here, in the mid-18th century, rose Fort Augusta – a formidable bastion on the raw edge of the American frontier, a silent sentinel against the tide of war, and a pivotal, though often overlooked, player in the epic struggle for North American dominance.

In the crucible of the French and Indian War (1754-1763), a conflict that was but the North American theatre of the larger Seven Years’ War, Pennsylvania found itself dangerously exposed. The colony’s pacifist Quaker roots had long dictated a reluctance to invest in military defense, leaving its western and northern settlements vulnerable to devastating raids by French-allied Native American tribes, particularly the Lenape (Delaware) and Shawnee. Following the disastrous defeat of General Edward Braddock in 1755 and the subsequent withdrawal of British regular forces, the frontier erupted in violence. Farmsteads were burned, families massacred, and a palpable fear gripped the colony. It was in this atmosphere of desperation that the Pennsylvania Assembly, shedding its pacifist ideals under immense pressure, authorized the construction of a chain of defensive outposts. Among them, Fort Augusta was to be the largest, the strongest, and arguably, the most strategically vital.

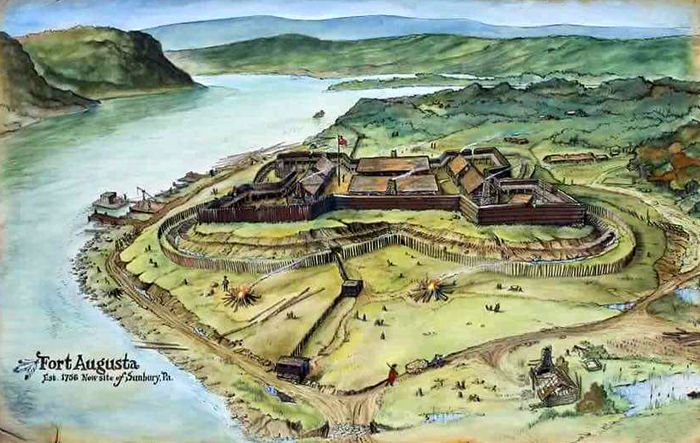

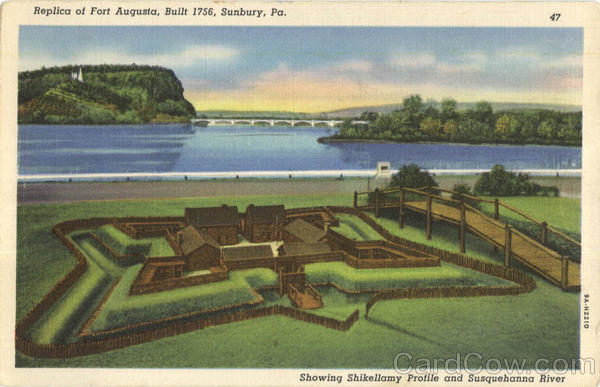

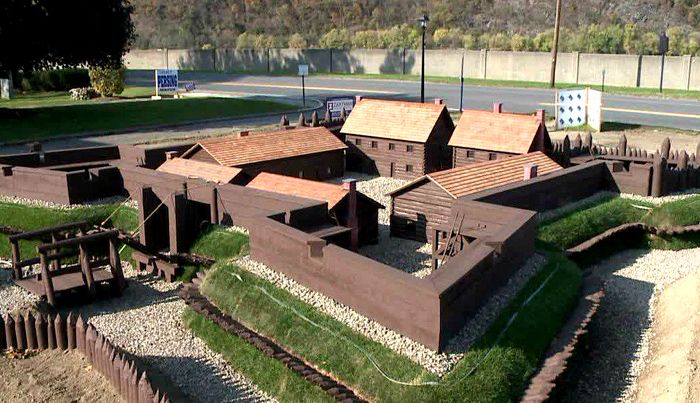

The man tasked with this monumental undertaking was Colonel William Clapham, an ambitious and somewhat controversial figure. His vision for Fort Augusta was grand: not merely a stockade, but a substantial, well-fortified stronghold capable of housing hundreds of men, cannon, and ample supplies. Construction began in July 1756. The chosen site, at the confluence of the two Susquehanna branches, was no accident. It commanded the main water routes into the vast interior of Pennsylvania, a crucial crossroads for both trade and military movements. From this vantage point, the fort could control access to the fertile valleys and serve as a forward operating base, protecting settlers and projecting colonial power.

Contemporary accounts described Fort Augusta as a "prodigious undertaking," a testament to the colony’s determination. Fashioned primarily from massive logs hewn from the surrounding forests, the fort was a square structure, approximately 200 feet on each side, surrounded by a palisade of sharpened timbers standing 14 feet high. At each corner, bastions – projecting defensive works – allowed for flanking fire, covering the walls and gate. Inside, barracks, a hospital, a powder magazine, and other essential buildings provided accommodation and support for a garrison that could swell to over 400 men. A deep ditch further enhanced its defenses, and heavy cannon, laboriously transported from Philadelphia, were mounted on the bastions, capable of firing shot weighing up to 18 pounds. Historians widely agree that Fort Augusta represented Pennsylvania’s most significant and costly defensive effort of the era. Its very presence was a bold declaration of colonial intent to secure its contested borders.

Life within the palisades of Fort Augusta was anything but idyllic. Despite its formidable appearance, the fort was incredibly isolated, a solitary outpost in a vast, untamed wilderness. Supplies, whether food, ammunition, or medicine, had to be painstakingly transported over long, arduous routes from Philadelphia, often under threat of ambush. This logistical nightmare meant that shortages were common, and the quality of provisions often poor. One observer at the time lamented the conditions, noting, "The men are sickly and discouraged, their provisions often spoiled, and the threat of the enemy ever present."

Disease, the silent killer of armies throughout history, was a constant companion. Smallpox, dysentery, and other ailments ravaged the garrison, often claiming more lives than enemy engagements. The psychological toll of isolation, the harsh weather, and the ever-present danger of ambush or attack led to widespread desertion, a common problem for frontier garrisons. The monotony of routine patrols, guard duty, and the arduous task of maintaining the fort’s defenses was broken only by the occasional skirmish or the terrifying rumors of approaching war parties. Yet, for all its challenges, Fort Augusta never faced a direct, sustained siege. Its sheer size and the implied strength of its garrison often deterred larger French or Native American forces, who preferred hit-and-run tactics against more vulnerable targets.

Beyond its physical walls, Fort Augusta played a crucial role in the complex web of intercultural dynamics that defined the Pennsylvania frontier. The land upon which it stood was ancestral territory for various Native American nations, who viewed the encroaching colonial settlements and forts with growing alarm. While some tribes actively allied with the French, others, particularly the powerful Iroquois Confederacy (the Six Nations), attempted to maintain neutrality, often playing the British and French against each other to preserve their own sovereignty.

Fort Augusta, therefore, was not just a military post; it was also a critical point of contact and, at times, negotiation. Its presence aimed to project strength, but also to serve as a base for diplomacy. The shifting allegiances of Native American tribes were paramount to the war’s outcome. A significant turning point came with the Treaty of Easton in 1758, a landmark agreement that saw the Iroquois and a number of Lenape and Shawnee leaders agree to peace with Pennsylvania and the British. This treaty, largely brokered by figures like Teedyuscung, the Lenape chief, and influenced by the British victories that year, significantly reduced the immediate threat to Fort Augusta and the Pennsylvania frontier. With the Lenape and Shawnee largely pacified or withdrawn, the fort’s immediate defensive urgency began to wane.

As the tide of the French and Indian War began to turn decisively in favor of the British, particularly after the fall of Fort Duquesne (renamed Fort Pitt) and Quebec, Fort Augusta’s strategic importance shifted. It remained a vital supply depot and a symbol of British authority in the region, but its role as a front-line defensive post diminished. Colonel Clapham was eventually replaced by Colonel James Burd, who oversaw the fort during a period of decreasing hostilities. By 1760, with the French threat largely neutralized, the garrison at Fort Augusta was significantly reduced. The costly maintenance of such a large fort in a now relatively peaceful frontier became an unsustainable burden for the Pennsylvania Assembly.

With the official end of the war in 1763, Fort Augusta was decommissioned. Its strategic purpose fulfilled, the land was eventually sold off. The massive logs and timbers that formed its palisades and buildings were repurposed by settlers eager to establish homes and farms in the newly secured territory. The nascent town of Sunbury began to rise from its foundations, inheriting the fort’s prime location at the river forks. While the fort itself faded into memory, its legacy lived on. It had anchored the frontier, protected the flow of settlers, and provided the critical base from which Pennsylvania’s expansion westward could eventually proceed.

During the American Revolution, the site of the former Fort Augusta once again became a point of strategic interest. Although the original fort no longer stood, the area was still recognized for its defensive advantages. A smaller stockade, Fort Muncy, was built nearby, and the former fort grounds served as a rallying point for local militia during the "Great Runaway" of 1778, when Native American and Loyalist raids once again threatened the Susquehanna Valley. The spirit of frontier defense, first embodied by Fort Augusta, was rekindled in the fight for independence.

Today, the physical remnants of Fort Augusta are sparse. Time and the growth of Sunbury have reclaimed much of the original footprint. However, a meticulously reconstructed blockhouse, a replica of one of the fort’s corner bastions, stands proudly on the original site, offering a tangible link to the past. This blockhouse, housing the Fort Augusta Museum, serves as a vital repository of the fort’s history, showcasing artifacts, maps, and interpretive exhibits that bring the 18th-century frontier to life. Visitors can explore the challenging lives of the soldiers, the intricate relationships with Native American tribes, and the broader context of the French and Indian War. Historical markers dot the landscape, ensuring that the fort’s story is not forgotten amidst the modern bustle.

Fort Augusta, the silent sentinel of the Susquehanna, represents more than just a military outpost. It embodies Pennsylvania’s reluctant embrace of defense, the sheer grit of its frontier settlers, and the complex, often violent, birth of a nation. It was a place of immense struggle, where soldiers battled not only external foes but also disease, isolation, and the unforgiving wilderness. Its story is a testament to the strategic foresight of its builders, the resilience of its garrison, and its enduring impact on the landscape and history of Pennsylvania. As the Susquehanna continues its timeless flow, the legacy of Fort Augusta whispers from the past, reminding us of the formidable challenges and profound sacrifices that shaped the American frontier.