The Silent Stones of Awatovi: A Tale of Faith, Conflict, and Catastrophe

On a desolate mesa in the vast, sun-baked landscape of northeastern Arizona, a cluster of silent stone ruins bears witness to a story both profound and tragic. This is Awatovi, once a vibrant Hopi village, whose name echoes with a chilling tale of cultural collision, internal division, and a catastrophic end that forever altered the course of indigenous history in the American Southwest. More than just an archaeological site, Awatovi stands as a stark reminder of the fragile balance between tradition and change, and the devastating consequences when that balance shatters.

For centuries before the arrival of Europeans, the Hopi people thrived on the arid mesas of what is now Arizona. Their lives were meticulously woven into the fabric of the land, guided by ancient spiritual traditions that emphasized harmony, community, and respect for all living things. They were skilled farmers, cultivating corn, beans, and squash in ingenious dry-farming techniques, and master artisans, creating intricate pottery, textiles, and kachina figures. Their villages, like Awatovi, were not merely dwellings but living expressions of their cosmology, designed to reflect the patterns of the universe.

Awatovi, meaning "place of the high bow" or "place of the rock where the bow is drawn," was one of the largest and oldest of the Hopi villages, perched atop Antelope Mesa. Its strategic location offered defensive advantages and access to vital resources. By the 16th century, it was a flourishing community, a hub of trade and culture, its multi-storied pueblos bustling with life, ceremonies, and the daily rhythms of an ancient civilization.

The serenity of this existence was irrevocably broken in the late 16th century with the arrival of the Spanish. Explorers like Francisco Vásquez de Coronado passed through the region in 1540, initially seeking the fabled Seven Cities of Gold. While no gold was found, the Spanish did discover a rich and complex indigenous society. Their true impact, however, came later, with the arrival of missionaries.

The early 17th century saw the establishment of a Spanish mission at Awatovi, dedicated to San Bernardo de Aguatubi. For the Spanish, the conversion of "heathen" souls was a divine imperative, and the Hopi represented a vast, untapped spiritual conquest. For the Awatovi, the arrival of the Franciscans was a complex proposition. Some saw opportunities for trade, new technologies, or even protection. Others viewed the foreign religion and its demands as a profound threat to their ancestral ways, an affront to the powerful kachina spirits and the cosmic order.

The mission at Awatovi became a focal point of this cultural clash. Churches were built, often with forced Hopi labor, and traditional religious practices were suppressed, sometimes brutally. Hopi men were made to cut their long hair, a sign of defiance to their traditions, and women were subjected to new social norms. Yet, despite the Spanish presence, Hopi religious practices continued, often in secret, beneath the floorboards of their kivas (underground ceremonial chambers) or in remote corners of the mesa. The missionaries, in their zeal, often failed to grasp the depth of Hopi spiritual resistance, viewing outward compliance as genuine conversion.

This tension simmered for decades, occasionally erupting into open rebellion. The most significant of these was the Pueblo Revolt of 1680, a coordinated uprising across the Pueblo lands that successfully drove the Spanish out of New Mexico for twelve years. The Hopi played a crucial role in this revolt, destroying the missions within their territory, including Awatovi’s, and reclaiming their religious freedom.

However, the period of Spanish absence did not bring complete peace. When the Spanish reconquered New Mexico in 1692, they renewed their efforts to re-establish missions. Awatovi, perhaps due to its earlier embrace of Spanish ways or its geographic isolation, became the first Hopi village to once again entertain Spanish overtures. This decision was not unanimous. It ignited a deep, irreconcilable schism within the village and among the wider Hopi Confederacy.

Some Awatovi residents, weary of conflict or perhaps enticed by Spanish goods and the promise of protection from hostile raiding tribes, advocated for renewed engagement with the missionaries. They saw the Spanish as a powerful force that could not be indefinitely resisted and believed accommodation was the only pragmatic path to survival. Others, the traditionalists, viewed this as an unforgivable betrayal of the Hopi Way, a surrender of their spiritual sovereignty and cultural identity. To them, the Spanish represented an existential threat to everything they held sacred.

This internal conflict festered, creating a fractured soul within Awatovi. The village became a symbol of division, a dangerous precedent for the other Hopi villages who had fiercely guarded their independence. The traditionalist factions among the other Hopi pueblos watched with growing alarm as Awatovi seemingly slipped back into the Spanish orbit. They feared that if Awatovi succeeded in its accommodation, it would weaken the collective resolve of the Hopi people and open the door for a full Spanish reoccupation.

The breaking point came in the bitter winter of 1700. The other Hopi villages – Oraibi, Walpi, Shongopavi, Mishongnovi, Shipaulovi – decided that Awatovi’s apostasy could no longer be tolerated. A grim council was held, and the decision was made: Awatovi must be eliminated, its example eradicated to preserve the spiritual and cultural integrity of the remaining Hopi.

Under the cloak of darkness and the biting cold of a December night, warriors from the other Hopi villages launched a devastating surprise attack on Awatovi. The oral traditions, passed down through generations of Hopi, describe a brutal and merciless assault. Men were reportedly killed in their kivas, trapped and suffocated by smoke from burning timbers, or executed if they resisted. Women and children were often spared but taken captive and dispersed among the other villages, effectively absorbing Awatovi’s population and preventing its resurgence. The village itself was systematically looted and then set ablaze, its structures collapsing into charred rubble.

The destruction of Awatovi was not merely a military act; it was a profound spiritual cleansing, a desperate measure to sever a cancerous limb from the body of the Hopi people. It was a reaffirmation of the Hopi Way, a stark lesson that deviation from core traditions could lead to utter annihilation. After the massacre, the site was deliberately left desolate, its stones silent witnesses to the violence, and its memory serving as a powerful deterrent against future apostasy.

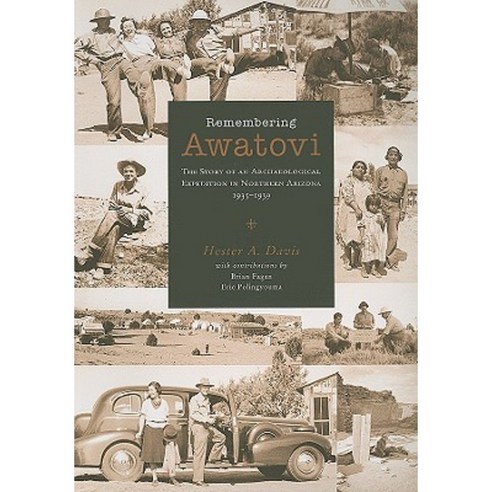

For centuries, Awatovi remained largely untouched, its story preserved in Hopi oral histories and whispered warnings. It was not until the late 19th and early 20th centuries that archaeologists, notably Jesse Walter Fewkes in 1892 and later John Otis Brew of Harvard University’s Peabody Museum in the 1930s, brought the ruins back to public attention.

Brew’s extensive excavations confirmed the oral traditions with chilling archaeological detail. He found evidence of the intense burning, charred timbers, and layers of ash. He unearthed a wealth of artifacts that painted a vivid picture of Awatovi’s complex history: indigenous pottery and tools mingled with Spanish rosaries, crucifixes, and metal implements. Most poignantly, Brew’s team uncovered exquisite kachina murals on kiva walls, depicting the vibrant spiritual life of the Hopi before the Spanish and even some later murals that showed evidence of being plastered over or modified, perhaps reflecting the conflict of beliefs within the village. The archaeological record provided a tangible, heartbreaking testament to the violence and cultural upheaval that had engulfed Awatovi.

Today, the Hopi people view Awatovi not as a place of shame, but as a sacred lesson, a potent symbol of the consequences of internal division and the importance of adhering to their ancestral spiritual path. The site remains deeply significant, yet also deeply sensitive. While its archaeological findings are invaluable for understanding the past, the Hopi maintain a custodial relationship with the land and its history, often expressing concern over the disturbance of ancestral remains and artifacts. For many Hopi, the story of Awatovi is not merely history; it is a living cautionary tale, a reminder of the strength found in unity and the dangers of allowing outside influences to fracture the community’s core values.

The silent stones of Awatovi speak volumes. They tell of a vibrant people thriving in harmony with their land. They tell of the seismic shock of European contact, the clash of empires and religions. They tell of a community torn apart by internal strife, forced to choose between adaptation and tradition. And ultimately, they tell of a tragic, decisive act by a people determined to preserve their identity, even at a terrible cost. Awatovi is a ghost village, its physical presence reduced to rubble, but its narrative continues to resonate, a powerful and enduring testament to the resilience of indigenous cultures and the profound lessons etched into the very landscape of the American Southwest. It is a place that demands not just historical understanding, but solemn reflection on the choices we make, and the echoes they leave for generations to come.