The Summer America Bled: Unearthing the Brutality of the 1919 Red Summer Riots

Nineteen nineteen was supposed to be a year of triumph. The Great War had ended, and American soldiers, both Black and white, were returning home, eager to rebuild their lives in a nation that had fought to "make the world safe for democracy." Yet, the peace abroad failed to translate to peace at home. Instead, the summer of 1919 became a searing inferno of racial violence, a period so brutal and widespread that civil rights activist and author James Weldon Johnson would famously dub it the "Red Summer."

The "red" in Red Summer was not a reference to communism, as some might assume given the era’s political anxieties. It was, chillingly, a reference to the blood that flowed in the streets of more than three dozen cities and towns across the United States. From the bustling metropolises of Chicago and Washington D.C. to the rural farmlands of Elaine, Arkansas, white mobs, often aided or abetted by law enforcement, unleashed a wave of terror against Black communities. This was not merely random violence; it was a systemic eruption of white supremacy, fueled by deep-seated racial animosity, economic competition, and the anxieties of a nation grappling with profound social change.

A Nation on the Brink: The Context of the Red Summer

To understand the intensity of the Red Summer, one must grasp the volatile cocktail of social and economic forces brewing in post-World War I America.

Firstly, the Great Migration was reshaping the demographic landscape of the nation. Millions of African Americans, fleeing the brutal oppression of Jim Crow laws, economic exploitation (especially sharecropping), and the constant threat of lynching in the South, had migrated north and west in search of better opportunities and greater freedom. This influx of Black labor into industrial cities like Chicago, Detroit, and Cleveland led to increased competition for jobs, housing, and social spaces, igniting resentment among working-class white communities.

Secondly, the return of Black soldiers from the war introduced a new dynamic. Having fought valiantly for their country overseas, often experiencing more freedom and respect in Europe than they had ever known at home, these veterans returned with a heightened sense of dignity and a refusal to revert to the subservient roles society prescribed for them. Many wore their uniforms proudly, a symbol of their service, but for many white Americans, especially in the South, this pride was seen as an affront to the established racial hierarchy. As W.E.B. Du Bois famously declared in the pages of The Crisis magazine, "We return from fighting. We return fighting." This sentiment of defiant self-defense would be a hallmark of the Red Summer.

Finally, underlying all of this was the pervasive and deeply entrenched white supremacy that defined American society. Jim Crow laws were the legal manifestation of this ideology, but it permeated every aspect of life – from housing covenants and employment discrimination to media portrayals and the justice system. The perceived threat of Black advancement, coupled with economic anxieties, created a powder keg waiting for a spark.

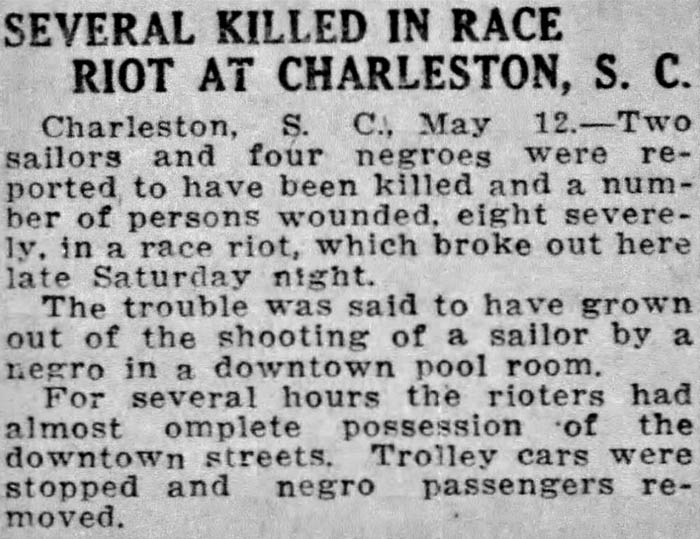

Flashes of Fire: Key Incidents of the Red Summer

While dozens of communities experienced racial violence, a few incidents stand out for their scale, brutality, or lasting impact:

Chicago, Illinois (July 27 – August 3): The most notorious and prolonged riot of the Red Summer began on a sweltering Sunday afternoon. A young Black teenager, Eugene Williams, drifted on a raft across an imaginary racial dividing line at a segregated Lake Michigan beach. He was struck by a stone thrown by a white man and drowned. When a white police officer refused to arrest the alleged assailant and instead arrested a Black man, tensions exploded. The riot lasted for 13 days, fueled by white street gangs, police inaction, and a deeply segregated city. By the time the Illinois National Guard finally restored order, 38 people were dead (23 Black, 15 white), 537 were injured, and over 1,000 Black families were left homeless, their homes destroyed. The Chicago riot vividly illustrated the systemic nature of racial segregation and the fragility of peace in a city divided by color lines.

Washington D.C. (July 19 – July 23): Just days before Chicago erupted, the nation’s capital experienced its own convulsion of violence. Fueled by sensational and often false newspaper reports of Black men assaulting white women, white servicemen – many still in uniform – began attacking Black residents on the streets. Black communities, particularly the vibrant U Street corridor, organized to defend themselves, leading to pitched battles. For four days, the city descended into chaos. The federal government, under President Woodrow Wilson, initially did little to intervene. Only when the violence escalated significantly, with white mobs attempting to storm Black neighborhoods, did Wilson finally dispatch troops to quell the unrest. By then, at least 15 people had died, and dozens were injured. The irony of the nation’s capital, a symbol of democracy, being engulfed in such racist violence was not lost on observers.

Elaine, Arkansas (September 30 – October 1): Perhaps the most horrific, and least known, incident of the Red Summer occurred in the rural delta region of Arkansas. This was not an urban riot but a massacre. Black sharecroppers, exploited and systematically cheated by white landowners, had secretly organized the Progressive Farmers and Household Union of America to demand fair prices for their cotton and better working conditions. When a meeting of the union was discovered, white planters and their allies launched a brutal assault. The pretext was the killing of a white railroad detective, though evidence suggests he was shot in self-defense by Black men guarding the meeting. White mobs, numbering in the hundreds and even thousands, including local law enforcement and deputized citizens, indiscriminately murdered Black men, women, and children. Federal troops were eventually called in, but rather than protecting Black lives, they often disarmed Black residents and rounded them up, turning them over to white mobs or authorities who subjected them to further abuse. The official death toll was listed as five white and 237 Black, but historians estimate that hundreds, possibly more than 800, Black people were killed. Twelve Black men were unjustly convicted of murder in sham trials, a gross miscarriage of justice that was eventually overturned by the Supreme Court in Moore v. Dempsey (1923), a landmark civil rights case.

Omaha, Nebraska (September 28): In another devastating event, a white mob of thousands surrounded the Douglas County Courthouse, where a Black man named Will Brown was being held on a dubious charge of assault. Despite the efforts of the mayor, Edward P. Smith, who was himself severely beaten and lynched by the mob, Brown was dragged from the courthouse, shot more than a thousand times, and his body was mutilated and set ablaze. The violence then spread, targeting Black homes and businesses in a chilling display of racial terror.

The Aftermath and Enduring Legacy

The Red Summer did not end with a definitive ceasefire. It slowly tapered off as the year concluded, leaving behind a trail of death, destruction, and trauma. While the federal government’s response was largely inadequate, marked by President Wilson’s silence on the issue of racial violence, the events of 1919 profoundly impacted the trajectory of the Civil Rights Movement.

For many African Americans, the Red Summer was a brutal awakening. It shattered any illusions that progress would come peacefully or that their service in the war would earn them respect at home. It demonstrated that racial violence was not just a Southern problem but a nationwide phenomenon. This realization fostered a renewed sense of urgency and a more militant approach to achieving civil rights.

Organizations like the NAACP saw a surge in membership and intensified their legal and advocacy efforts. The events in Elaine, for instance, propelled the NAACP into a critical legal battle that eventually reached the Supreme Court, setting an important precedent for federal intervention in state court cases involving racial injustice. The Red Summer also contributed to the rise of Black nationalist movements, such as Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), which advocated for Black self-reliance and, for some, a return to Africa, disillusioned by the prospects of equality in America.

The Red Summer of 1919 serves as a stark, bloody reminder of America’s deep-seated racial pathologies and the often-overlooked brutality of its past. It underscores the vital role of Black self-defense in the face of systemic violence and highlights the failures of institutions to protect their most vulnerable citizens. A century later, as the nation continues to grapple with issues of racial injustice, police brutality, and white supremacy, the lessons of the Red Summer remain hauntingly relevant, urging us to confront the historical roots of present-day inequalities and to strive for a future where such a summer can never again stain the fabric of American society. The blood spilled in 1919 cries out for remembrance, understanding, and a commitment to genuine racial equity.