The Tempest in Southampton: Nat Turner’s Rebellion and America’s Enduring Scar

By [Your Name/Journalist’s Pen Name]

SOUTHAMPTON COUNTY, VIRGINIA – August 21, 1831. In the oppressive heat of a Southern summer night, an unimaginable terror unfurled across the quiet farmlands of Southampton County, Virginia. What began as a clandestine gathering of enslaved men, fueled by prophetic visions and an unyielding desire for freedom, quickly escalated into the deadliest slave revolt in American history. Led by a deeply religious and fiercely intelligent enslaved man named Nat Turner, this rebellion, though short-lived, would send shockwaves through the antebellum South, forever altering the landscape of slavery and the trajectory of a nation hurtling towards civil war.

The reverberations of that bloody August week still echo through the annals of American history, a chilling testament to the brutal realities of human bondage and the desperate measures taken to escape its grasp.

The Peculiar Institution and the Seeds of Rebellion

To understand Nat Turner’s rebellion, one must first grasp the pervasive and brutal nature of slavery in the American South. Often euphemistically called the "peculiar institution," it was an economic, social, and political system built on the forced labor and dehumanization of millions of African people and their descendants. Enslaved individuals were considered property, bought and sold, their families routinely torn apart, their bodies subjected to unremitting toil and violence, and their spirits systematically crushed.

Yet, resistance was not uncommon. From subtle acts of sabotage to outright flight, enslaved people continually challenged their bondage. There had been other significant plots and uprisings – Gabriel Prosser’s conspiracy in Richmond in 1800, and Denmark Vesey’s planned revolt in Charleston in 1822 – both of which were uncovered before they could fully materialize, leading to swift and brutal suppression. But Nat Turner’s rebellion was different. It caught the South entirely by surprise, shattering the pervasive myth that enslaved people were largely content or incapable of organized, violent resistance.

The Prophet of Southampton

Nat Turner was born into slavery in Southampton County, Virginia, on October 2, 1800. From an early age, he exhibited remarkable intelligence and an intensely spiritual nature. He learned to read and write, a rarity for enslaved people, and spent countless hours studying the Bible, often fasting and praying. He became known among his peers as "the Prophet," experiencing vivid visions that he interpreted as divine communications. He believed he was destined for a great purpose, chosen by God to lead his people out of bondage.

His visions grew increasingly apocalyptic. He saw "white spirits and black spirits engaged in battle," and observed drops of blood on corn, symbols that he believed portended a coming conflict. In February 1831, a solar eclipse, which made the sun appear bluish-green, confirmed his conviction that the time for action was near. He shared his interpretations with a small, trusted group of fellow enslaved men: Henry, Hark, Nelson, and Sam. The signal for their uprising, he declared, would be another atmospheric phenomenon.

The Spark Ignites: August 21-22, 1831

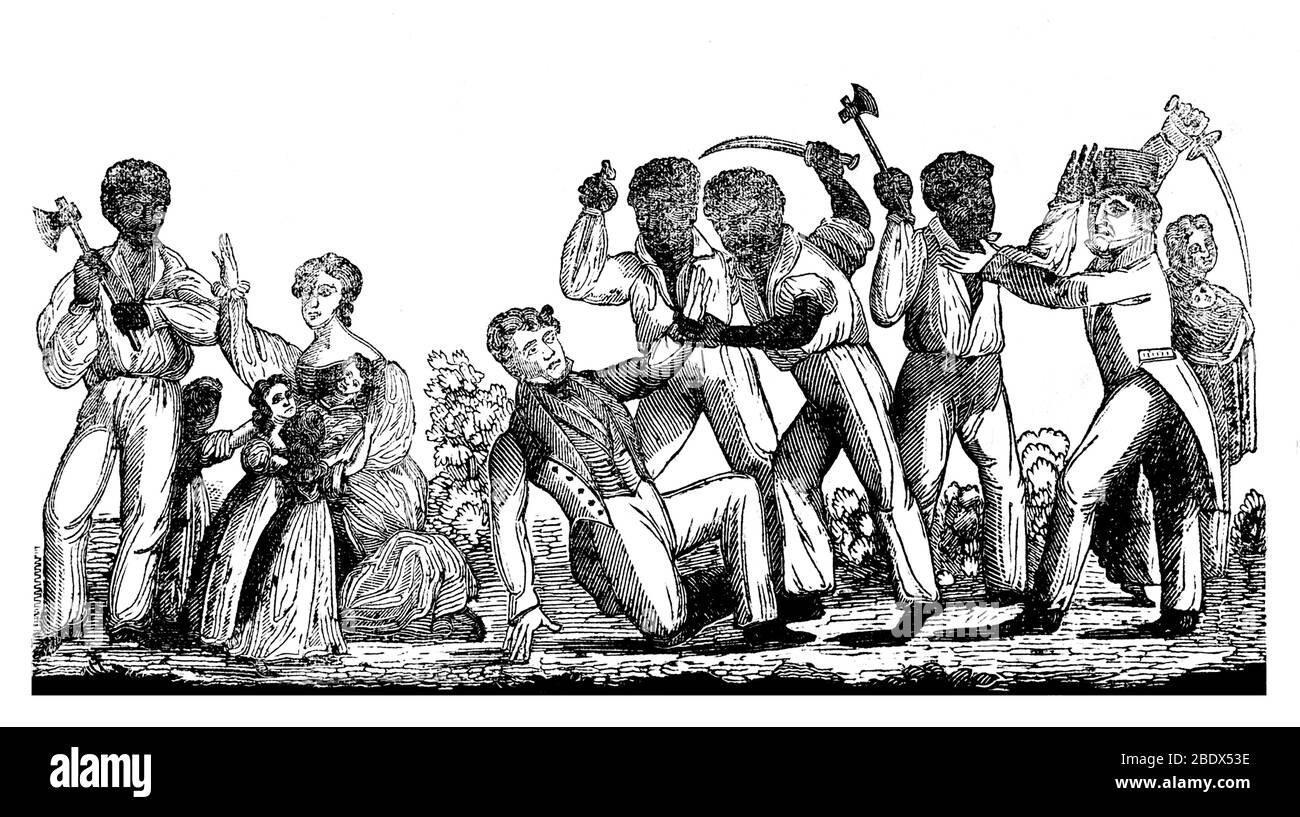

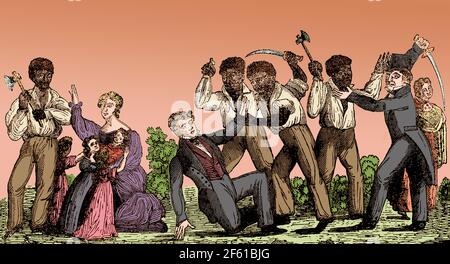

That signal came on August 13, 1831, when an atmospheric disturbance caused the sun to appear discolored. For Turner, this was the unmistakable sign. Initially planned for August 21st, Turner fell ill, postponing the start. But on the night of August 21st, he gathered his small band in the woods near Cabin Pond. Armed with axes, knives, and a few rudimentary firearms, they began their horrific mission.

Their first target was the home of Joseph Travis, Turner’s owner. They entered the house silently, killing Travis, his wife, and their young son. The act was swift, brutal, and utterly without mercy. From there, the rebels moved systematically from plantation to plantation, killing every white person they encountered, sparing no one, not even women and children. The rebels’ numbers grew as they marched, forcing other enslaved men to join them, swelling their ranks to an estimated 60 to 70 individuals.

"We were to proceed directly to Jerusalem, where a depot of arms and ammunition was provided to supply us, and from thence to spread the work of death and destruction throughout Virginia," Turner later recounted in his Confessions. Their objective was not merely escape but to inspire a widespread uprising, to strike such terror that the institution of slavery itself would crumble.

A Path of Blood and Terror

For nearly 48 hours, Nat Turner’s rebellion carved a bloody path through Southampton County. The precise number of victims varies slightly across historical accounts, but it is generally accepted that between 55 and 65 white men, women, and children were killed. The killings were deliberate and methodical, designed to maximize terror and signal the absolute resolve of the rebels.

The news of the uprising spread like wildfire, igniting widespread panic across Virginia and beyond. White families fled their homes, seeking refuge in towns or further north. Militia units, hastily assembled, converged on Southampton County from surrounding areas, their mission clear: suppress the rebellion and hunt down its perpetrators.

The rebels, lacking a coherent military strategy and overwhelmed by the superior numbers and firepower of the militias, were eventually dispersed. On the morning of August 23rd, they clashed with a larger militia force near Dr. Simon Blunt’s plantation. The rebels were routed, their dreams of widespread liberation shattered. Many were killed on the spot, others captured.

The Hunt and the Confessions

Nat Turner, however, managed to evade capture for an astonishing 70 days. He hid in the dense woods and swamps of the Great Dismal Swamp, surviving on meager rations, a ghost in the landscape he knew so intimately. His continued freedom fueled the white community’s terror, leading to a brutal and indiscriminate crackdown. Hundreds of enslaved and free Black people, many with no connection to the rebellion, were rounded up, tortured, and murdered by enraged militias and vigilantes. Estimates suggest that between 100 and 200 innocent Black people were killed in the retribution, a chilling precursor to the violence of the coming Civil War.

Finally, on October 30, 1831, Turner was discovered hiding in a cave by a local farmer. He surrendered without resistance. His capture brought a collective sigh of relief to the South, but it also raised uncomfortable questions about the nature of the enslaved population.

While awaiting trial, Turner was interrogated by Thomas Ruffin Gray, a local lawyer. Gray, eager to understand Turner’s motives and perhaps to profit from the sensation, transcribed Turner’s narrative, publishing it as The Confessions of Nat Turner. This document, though controversial and undoubtedly shaped by Gray’s own biases and agenda, remains the primary source for understanding Turner’s personal motivations and his account of the rebellion.

In the Confessions, Turner articulated his divine mandate: "I had a vision—and I saw white spirits and black spirits engaged in battle; and the sun was darkened—the thunder rolled in the Heavens, and blood flowed in streams—and I heard a voice saying, ‘Such is your luck, such you are called to see, and let it come rough or smooth, you must surely bear it.’"

On November 5, 1831, Nat Turner was tried in the Southampton County Court. He pleaded not guilty, claiming he was inspired by God. He was swiftly convicted and sentenced to hang. On November 11, 1831, at the age of 31, Nat Turner was executed in Jerusalem, Virginia. His body was flayed, beheaded, and quartered, his remains scattered as a gruesome warning.

The Chilling Aftermath and Enduring Legacy

The immediate aftermath of Nat Turner’s rebellion was a tightening of the chains of slavery across the South. White fear, already palpable, escalated into a paranoia that manifested in a series of repressive laws. State legislatures passed stricter "Black Codes" that curtailed the few freedoms previously allowed to both enslaved and free Black people. It became illegal for enslaved people to learn to read or write, to gather in groups without white supervision, or to preach without white ministers present. The laws were designed to prevent any future insurrections, but they also served to further entrench the institution of slavery and harden the resolve of Southern slaveholders.

The rebellion also had a profound impact on the national debate over slavery. In the North, it galvanized abolitionist sentiment, proving to many that slavery was not merely an economic system but a moral abomination that could lead to extreme violence. For the South, however, it reinforced the belief that slavery was a necessary evil, essential for maintaining social order and white supremacy. It pushed the South further into a defensive posture, stifling internal dissent against slavery and contributing to the region’s increasing isolation from the rest of the nation.

Nat Turner remains a complex and controversial figure in American history. To some, he was a murderous fanatic, a terrorist who brought unspeakable violence to innocent families. To others, he was a freedom fighter, a prophet, and a martyr who dared to strike a blow against an inherently unjust and brutal system. His rebellion, born of desperation and divine conviction, laid bare the inherent violence of slavery and foreshadowed the cataclysmic conflict that would ultimately tear the nation apart.

The events of August 1831 in Southampton County serve as a stark reminder of the enduring scars of slavery and the profound human cost of denying liberty. Nat Turner’s rebellion, a brief but bloody chapter, stands as a testament to the indomitable spirit of resistance and a chilling echo of a past that continues to shape America’s present.