The Thunder at Mine Creek: Kansas’s Pivotal Cavalry Clash

October 25, 1864. The air over eastern Kansas hung heavy with the chill of autumn and the scent of impending conflict. For weeks, the vast, beleaguered Confederate army of Major General Sterling Price had been racing across Missouri, a desperate gambit to salvage the South’s fading hopes in the Trans-Mississippi West. Now, with Union cavalry nipping at their heels and the Kansas border looming, Price’s exhausted command found itself trapped on the treacherous banks of Mine Creek, near the small, unassuming settlement of Paris. What unfolded there in the early morning light would become one of the most decisive, and often overlooked, cavalry engagements of the American Civil War – a thunderous, saber-rattling maelstrom that sealed the fate of Price’s Raid and effectively ended large-scale Confederate operations west of the Mississippi.

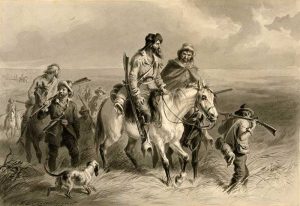

Often overshadowed by the epic clashes in the Eastern Theater, the Battle of Mine Creek – sometimes colloquially referred to as the "Battle of Paris, Kansas" due to its proximity to the hamlet – was a brutal, swift, and utterly conclusive affair. It pitted mounted soldier against mounted soldier in a mêlée of sabers, pistols, and carbines, a raw display of cavalry warfare that would become a poignant symbol of the war’s final, desperate throes.

The Grand Design and a Desperate Gamble

By the autumn of 1864, the Confederacy was a dying ember. Ulysses S. Grant had Robert E. Lee pinned down at Petersburg, and William Tecumseh Sherman was carving a path of destruction through Georgia. In the Trans-Mississippi Department, Confederate fortunes were equally grim. Yet, a flicker of hope, or perhaps delusion, still burned in the mind of Major General Sterling Price. A former governor of Missouri and a seasoned, if often outmaneuvered, commander, Price harbored a grand vision: to reclaim Missouri for the South, disrupt Union supply lines, influence the upcoming presidential election, and recruit thousands of fresh troops from a state he believed was ripe for rebellion.

On August 29, 1864, Price launched his "Great Raid," leading an army of some 12,000 men, mostly cavalry, from Arkansas into Missouri. It was a formidable force, though many were poorly equipped and ill-trained. His objectives were ambitious: capture St. Louis, seize the arsenal, and then swing west to take Jefferson City. But the raid quickly bogged down. Union forces, though initially scattered, rapidly coalesced under the command of Major General Samuel R. Curtis and Major General Alfred Pleasonton. Price’s advance on St. Louis was thwarted, and his assault on Jefferson City proved futile.

The strategic objectives unmet, Price’s raid transformed into a desperate dash west, his army becoming less a conquering force and more a retreating column burdened with a massive wagon train of supplies, stolen goods, and even a few captured cannons. The relentless Union pursuit, spearheaded by Pleasonton’s cavalry division, turned the retreat into a harrowing ordeal. The Confederates fought a series of rearguard actions, most notably at Westport on October 23rd – a battle so large and complex it’s often called the "Gettysburg of the West" – where Price suffered a significant defeat.

The Race to the Border

Following Westport, Price’s army was in full retreat, heading south along the old Fort Scott Road, desperately trying to escape into the relative safety of Indian Territory (modern-day Oklahoma) or Arkansas. Their pursuers, primarily the cavalry divisions of Major General James G. Blunt and Brigadier General John B. Sanborn, were hot on their heels, driven by a fierce determination to crush Price’s command once and for all.

The Confederate column, stretched for miles, was a chaotic mix of weary soldiers, civilians, and a cumbersome train of some 400 wagons. Exhaustion, hunger, and dwindling ammunition plagued Price’s men. "We marched and starved and froze and fought," one Confederate veteran later lamented, capturing the spirit of the arduous retreat. The Union cavalry, though also fatigued, was buoyed by their recent victories and the scent of a decisive kill.

On the evening of October 24th, Price’s lead elements reached Mine Creek, a relatively small stream that, in normal conditions, would pose little challenge. However, recent rains had swollen the creek, turning its banks into treacherous, muddy quagmires and making the ford difficult to cross. With a significant portion of his army, including many wagons and artillery pieces, still struggling to cross the swollen creek, Price ordered a halt for the night, intending to complete the crossing in the morning. He established a defensive line on the west bank, hoping to buy time for his beleaguered command.

The Morning Maelstrom: October 25, 1864

Dawn on October 25th broke cold and foggy. As the sun struggled to burn through the mist, the sounds of Price’s army attempting to cross Mine Creek filled the air – the creaking of wagons, the shouts of teamsters, the splashing of horses. Confederate Major General John S. Marmaduke, commanding the rearguard, tried to maintain order, but the situation was rapidly deteriorating into a bottleneck of men, horses, and materiel.

Suddenly, out of the morning mist, appeared the advance elements of Union cavalry: first, a brigade under Colonel Frederick W. Benteen (who would later gain fame at the Little Bighorn), part of Blunt’s division, followed closely by Sanborn’s brigade. The sight that greeted them was astonishing: a massive, disorganized mass of Confederates struggling to cross the creek, their flank exposed, their attention divided.

Without hesitation, and despite being significantly outnumbered at the point of attack, Benteen ordered a charge. The ground thundered as some 2,500 Union cavalrymen, many of them Kansans and Missourians with a personal stake in the outcome, bore down on the Confederate line. "It was a wild, desperate charge," recalled Captain Henry E. Palmer of the 11th Kansas Cavalry, "one of the most complete and disastrous routs of the war."

The Confederates, caught completely by surprise and already demoralized, crumbled under the ferocious assault. Sabers flashed, pistols barked, and the air filled with the shouts of men and the screams of horses. The Union troopers crashed into Marmaduke’s line, driving them back towards the treacherous creek. The steep, muddy banks of Mine Creek became a deathtrap. Horses stumbled, men fell, and the crossing became a scene of utter chaos and panic.

The battle, though relatively small in scale compared to battles like Gettysburg or Antietam, was incredibly intense and personal. It was a cavalryman’s fight, pure and unadulterated. Union troopers, many armed with the new Spencer repeating carbines, had a decided advantage in firepower, but it was the cold steel of the saber that decided the day.

Within a mere 30 minutes, the battle was over. The Confederate line shattered. Union forces captured over 600 prisoners, including two Confederate generals: John S. Marmaduke himself and Brigadier General William L. Cabell. Hundreds more were killed or wounded. Price’s army, already battered, was now utterly broken, its rearguard decimated, its morale shattered.

The Aftermath and Lingering Legacy

The Battle of Mine Creek was a catastrophic defeat for Sterling Price. Though he managed to escape with the remnants of his army, the raid was effectively over. The long, agonizing retreat continued south through Arkansas and into Indian Territory, harassed by Union forces and suffering from disease, desertion, and starvation. By the time Price reached Texas, his once-formidable army was a shadow of its former self, having lost thousands of men, nearly all its artillery, and its entire wagon train.

Mine Creek was more than just another skirmish; it holds a unique place in Civil War history. It is widely considered the last major cavalry battle of the American Civil War and one of the largest mounted engagements ever fought on American soil. It was a textbook example of a decisive cavalry victory, demonstrating the power of a well-executed charge against a surprised and disorganized enemy.

For Kansas, the battle held particular significance. It marked the end of any serious Confederate threat to the state, which had long endured border raids and guerrilla warfare. The bravery of the Kansan and Missourian Union troops, fighting on their home ground, was particularly notable.

Today, the Mine Creek Battlefield State Historic Site near Pleasanton, Kansas (a few miles from where Paris, Kansas, once stood), preserves a significant portion of the battleground. Visitors can walk the fields where Union and Confederate cavalry clashed, stand on the banks of the creek that proved to be such a formidable obstacle, and reflect on the courage and desperation of the men who fought there. Interpretive markers and a visitor center offer insights into the battle and its broader context within the Civil War.

The thunderous clash at Mine Creek, though often overshadowed by its larger Eastern counterparts, was a pivotal moment in the Civil War’s western theater. It was the twilight of a Confederate dream, a desperate gamble that ended in a swift and decisive Union victory. It stands as a testament to the brutal effectiveness of cavalry warfare and a powerful reminder that even in the war’s final days, the fight for the Union was waged with fierce determination and profound sacrifice, right down to the rolling prairies of eastern Kansas.