The Unbroken Spirit: Unearthing the Chumash Revolt of 1824

The California landscape, often romanticized for its golden sunshine and rolling hills, holds within its memory a darker chapter – one of profound injustice, cultural annihilation, and fierce, desperate resistance. On a seemingly ordinary day, February 21, 1824, this simmering resentment erupted into the largest and most significant indigenous uprising in California’s mission history: the Chumash Revolt. It was a desperate cry for freedom, a poignant testament to the unbroken spirit of a people pushed to the brink, echoing through the canyons and valleys that once belonged solely to them.

For decades leading up to that fateful day, the Chumash people, along with countless other indigenous groups across Alta California, had endured a life of forced labor and cultural suppression under the Spanish, and later Mexican, mission system. What began as an evangelical endeavor to convert "heathen" souls had devolved into a complex, often brutal system of economic exploitation and social control. The missions, ostensibly centers of spiritual guidance, functioned more as agricultural enterprises and labor camps, built upon the backs of their "neophytes" – the missionized Native Americans.

Life within the mission walls was a stark departure from the Chumash’s millennia-old traditions of hunting, gathering, and sophisticated maritime culture. Their ancestral lands, once bountiful and freely roamed, were now enclosed and exploited for mission gain. Traditional spiritual practices were forbidden, languages suppressed, and family structures disrupted. Disease, introduced by Europeans, ravaged their communities, dramatically reducing their population from an estimated 20,000 at the time of European contact to just a few thousand by the early 19th century.

The daily routine was one of relentless toil, from dawn to dusk. Men and women were forced to work in fields, vineyards, workshops, and kitchens, producing goods for the mission and the Spanish colonial economy. Punishment for perceived transgressions, disobedience, or attempts to flee was swift and often brutal, ranging from public floggings to imprisonment. As Father Presidente Mariano Payeras lamented in an 1818 letter, describing the neophytes, they were "poor, naked, and hungry." This stark reality painted a different picture from the idyllic mission narratives often propagated.

By 1824, the situation had grown even more dire. Mexican independence from Spain in 1821 brought little relief and, in some ways, exacerbated the plight of the mission Indians. The newly independent Mexican government was financially strapped. Supplies to the missions dwindled, and the soldiers guarding them, poorly paid and provisioned, became increasingly reliant on mission resources, leading to even greater demands on the native laborers. The promises of land and freedom that had been vaguely dangled by the new government remained unfulfilled, adding to a profound sense of betrayal and hopelessness.

The immediate catalyst for the revolt was a relatively minor, yet symbolically potent, incident at Mission Santa Inés. On February 21, 1824, a Chumash neophyte was brutally flogged by a Mexican corporal for an alleged minor offense. This act of violence, one of many, proved to be the final spark. The accumulated grievances – the forced labor, the cultural degradation, the rampant disease, the corporal punishment, the unfulfilled promises, and the sheer indignity of their existence – ignited.

What followed was not a spontaneous, isolated outburst but a remarkably coordinated uprising. Almost simultaneously, the Chumash at Mission Santa Inés, Mission La Purísima Concepción, and Mission Santa Barbara rose up. This coordination speaks volumes about the underlying networks of communication and shared grievances that existed among the missionized communities, despite the efforts of the friars to keep them isolated.

At Mission Santa Inés, the Chumash overwhelmed the small guard, setting fire to some of the mission buildings. The friars and soldiers barricaded themselves inside the church until reinforcements arrived, eventually driving the Chumash from the mission. But this was only the beginning.

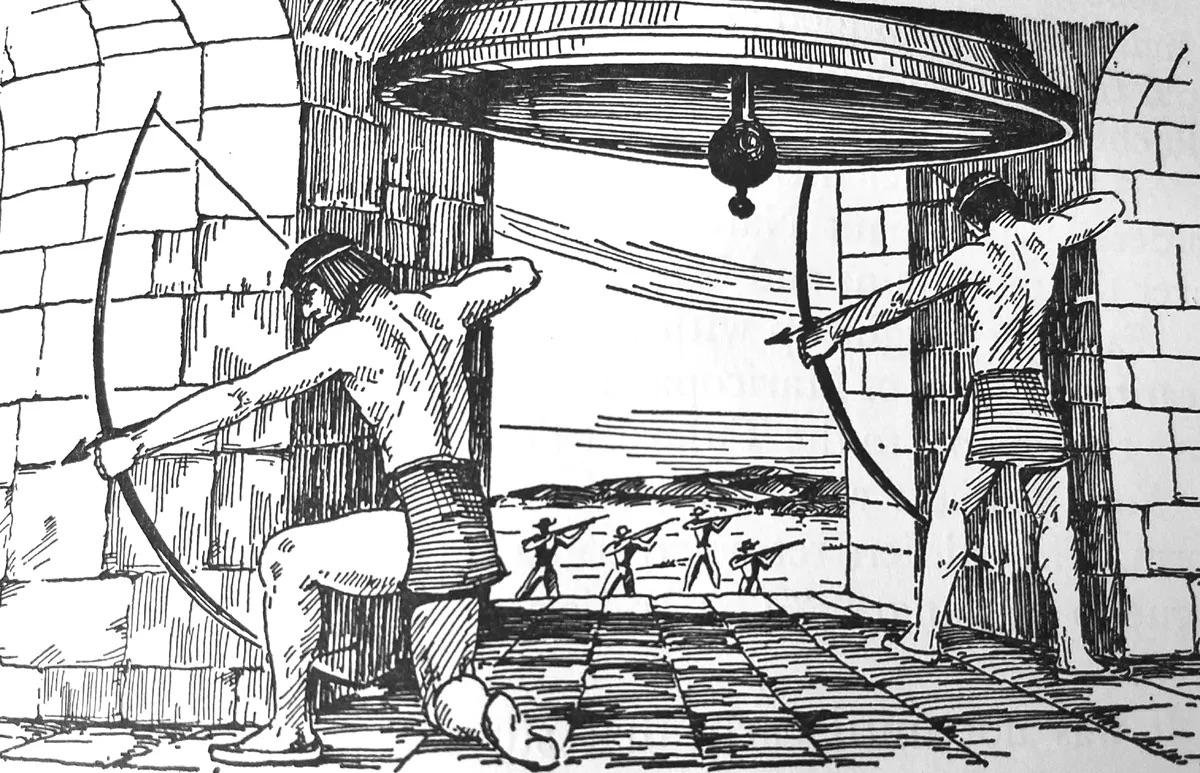

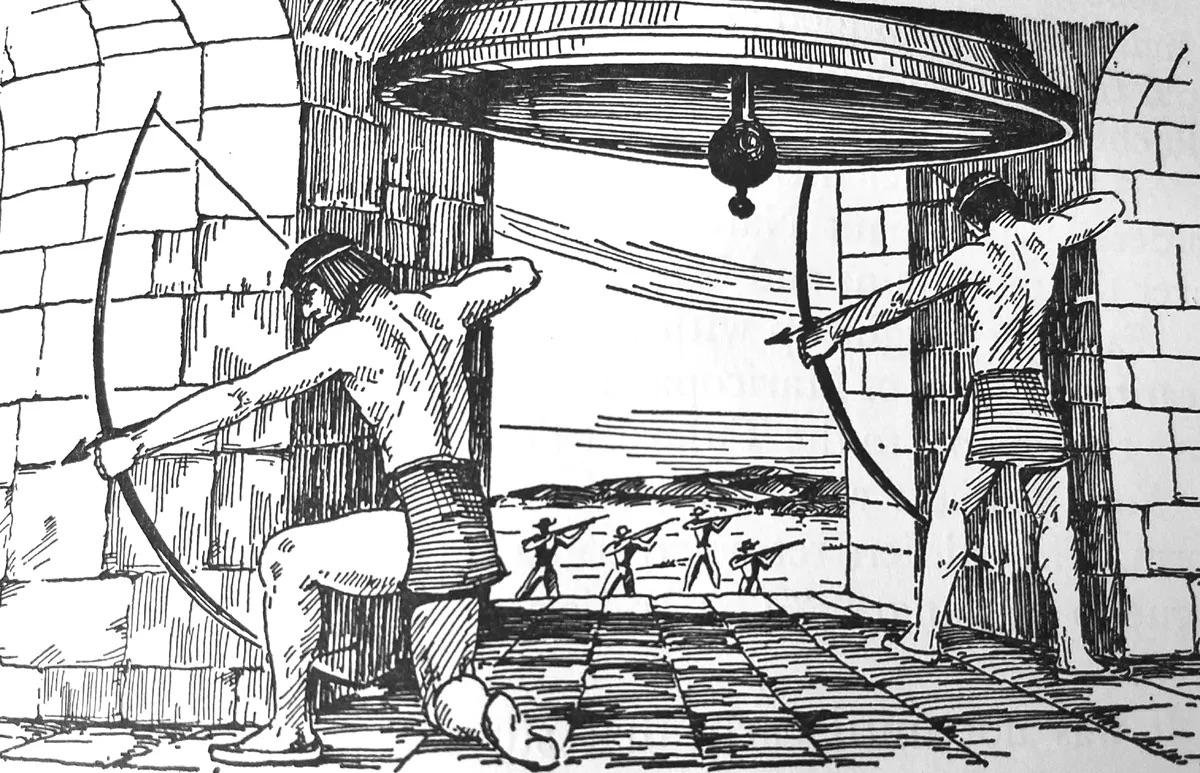

The most dramatic events unfolded at Mission La Purísima Concepción. Here, the Chumash, led by figures like Pacomio, a skilled artisan and former mission alcalde (an indigenous leader appointed by the friars), took full control of the mission. They disarmed the soldiers, took the friars and their families captive (though notably, they were treated with respect and not harmed), and transformed the mission into a fortified village. This was no mere riot; it was an act of strategic occupation. The Chumash repurposed looms for barricades, dug trenches, and, in a truly astonishing feat of improvisation, even managed to mount and fire the mission’s two small cannons, demonstrating a remarkable adaptability and understanding of their captors’ technology. They flew a flag of their own design, a testament to their desire for self-determination.

At Mission Santa Barbara, the Chumash confronted the mission guard in a pitched battle. Armed with traditional weapons – bows and arrows, lances, and slings – they faced muskets and cannon fire. Despite their bravery, the technological disparity was immense. After several hours of fighting, realizing they could not hold the mission, a significant portion of the Chumash population, including women, children, and elders, made a courageous decision. They abandoned the mission and fled eastward over the rugged Santa Ynez Mountains, seeking refuge in the remote Tulares Valley (modern-day San Joaquin Valley), a traditional wintering ground and a place of relative freedom beyond the immediate reach of Spanish/Mexican authority.

The Mexican authorities, caught off guard, quickly mobilized. Governor Luis Argüello dispatched punitive expeditions. The first, led by Lieutenant Romualdo Pacheco, engaged the fortified Chumash at La Purísima. After a fierce battle lasting several hours, Pacheco’s forces, with their superior firearms, overwhelmed the defenders. Many Chumash were killed, wounded, or captured. Pacomio and other leaders were arrested, later to face trial and severe punishment, including execution.

Meanwhile, a larger expedition, led by Captain Pablo de la Portilla, pursued the hundreds of Chumash who had fled to the Tulares. The journey was arduous, fraught with hunger and danger. When Portilla’s forces finally located the Chumash encampment, they found a community weary but not broken, prepared to defend their newfound, albeit temporary, freedom.

What followed was a tense standoff and a series of negotiations. Unlike many other colonial encounters, these negotiations involved intermediaries, including Franciscan friars like Father Antonio Ripoll, who had served at Santa Barbara and knew many of the fleeing Chumash. The Chumash, through their leaders, expressed their grievances: their desire for fair treatment, an end to corporal punishment, and a measure of autonomy. The Mexican authorities, facing the logistical challenge of subduing a large population in remote territory and perhaps wary of further bloodshed, offered a pardon for those who returned to the missions peacefully.

After much deliberation, and with the grim realization that their resources were limited and continued resistance would lead to further suffering, many of the Chumash from the Tulares agreed to return. It was a pragmatic decision, born of exhaustion and the desperate hope for a better future, rather than a genuine surrender of their principles. By June 1824, most had returned to Santa Barbara and other missions. However, some chose to remain in the Tulares, clinging to their hard-won freedom, forging new lives away from the missions’ suffocating embrace.

The immediate aftermath of the revolt was a period of intense scrutiny and debate within the Mexican government regarding the future of the mission system. While the Chumash were ostensibly pardoned, the conditions they returned to were largely unchanged. The underlying issues of forced labor, cultural suppression, and lack of basic human rights persisted. The revolt, however, had exposed the fragility of the mission system and the deep-seated discontent it fostered. It contributed to the growing calls for secularization, which eventually came in the 1830s, leading to the dismantling of the missions as religious institutions and the redistribution of their lands – though rarely to the benefit of the native peoples.

The Chumash Revolt of 1824 remains the largest and most significant indigenous uprising in California’s mission era. It was a powerful, albeit ultimately tragic, testament to the Chumash people’s enduring spirit and their fierce desire for self-determination. It highlighted their capacity for organization, strategic thinking, and profound courage in the face of overwhelming odds. It was a moment when they refused to be passive victims, choosing instead to fight for their dignity and their freedom.

For contemporary Chumash communities, the Revolt of 1824 is not merely a historical footnote but a living memory, a powerful symbol of their ancestors’ resilience and a source of inspiration. It is a reminder of the strength embedded in their cultural identity and the unwavering pursuit of justice. The echoes of that desperate cry for freedom continue to resonate through the mission walls and across the golden hills of California, a poignant and necessary reminder that history is not always written by the victors, and that the spirit of defiance, even in the darkest of times, can never be truly extinguished.