The Unconquered Heart of California: The Pit River Tribe’s Enduring Fight for Land and Legacy

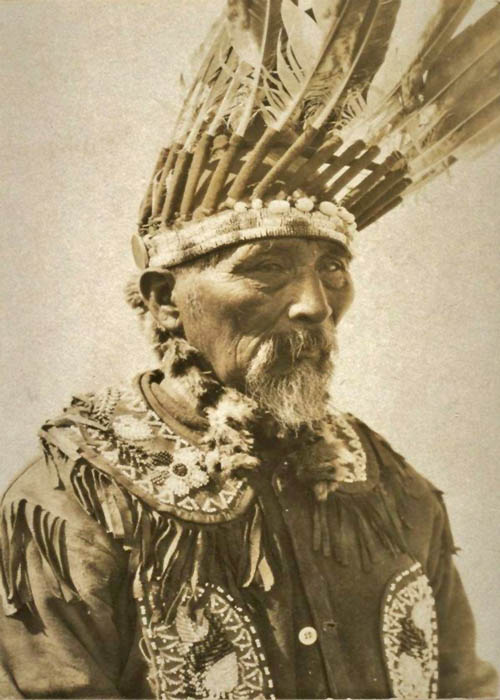

NORTHEASTERN CALIFORNIA – The Pit River, a serpentine artery of life, winds its way through the rugged, volcanic landscape of northeastern California. For millennia, its waters have sustained the Ajumawi and Atsuge peoples, collectively known today as the Pit River Tribe. More than just a river, it is the lifeline, the spiritual center, and the very foundation of an identity forged in resilience against centuries of encroachment and dispossession. Their story is a powerful testament to an unyielding spirit, deeply rooted in the land they have never truly surrendered.

Unlike many other Indigenous nations in California, the Pit River Tribe holds a unique and poignant distinction: they never signed a treaty ceding their ancestral lands to the United States government. This fundamental fact lies at the heart of their protracted struggles, particularly their century-long battle with Pacific Gas & Electric (PG&E) over the hydroelectric dams that harness the power of their sacred river. It’s a fight for sovereignty, for environmental justice, and for the cultural survival of a people who have endured unthinkable hardships.

A Land Before Time: The Ancestral Domain

For thousands of years, long before the first European boot sullied the pristine earth, the Pit River people thrived across a vast territory spanning parts of present-day Modoc, Shasta, Lassen, and Siskiyou counties. Their traditional lands encompassed the majestic Mount Shasta, the sprawling Hat Creek Valley, and the intricate network of streams, rivers, and volcanic formations that provided abundant resources. They were skilled hunters and gatherers, their lives meticulously interwoven with the cycles of salmon runs, acorn harvests, and the migrations of deer and elk.

The tribe is comprised of eleven distinct bands – the Achomawi (including the Ajumawi, Atsuge, Ilmawi, Itsatawi, Aporige, Astariwawi, Hammawi, and Hewisedawi) and the Palaihnihan (including the Madesi and Kosalektawi). Each maintained its own identity and territory but shared a common cultural heritage, a deep reverence for the land, and a sophisticated understanding of ecological balance. Their languages, part of the Palaihnihan language family, reflected their intimate knowledge of their environment, with words for every plant, animal, and geological feature.

The Gold Rush and the Shattering of Worlds

The 1849 Gold Rush irrevocably shattered this ancient equilibrium. Waves of prospectors, settlers, and cattle ranchers poured into California, bringing with them disease, violence, and a ravenous hunger for land and resources. The Pit River people, like countless other Indigenous communities, faced a brutal campaign of extermination and displacement. Massacres were common, and their traditional ways of life were systematically dismantled.

"Our ancestors witnessed unspeakable horrors," says a tribal elder, who prefers to remain anonymous, her voice tinged with the weight of generations. "They saw their families murdered, their homes burned, their fishing weirs destroyed. But even then, they never gave up. They held onto the memory of this land, because it is who we are."

Unlike other tribes who were forced onto reservations through often fraudulent treaties, the Pit River people’s resistance and the remoteness of their lands meant they were never officially "conquered" or compelled to sign away their aboriginal title. This legal ambiguity, however, did not spare them from the relentless tide of colonization. Their lands were illegally seized, and their access to traditional hunting and fishing grounds was severely restricted. Many were scattered, living on the fringes of their own homelands, struggling to survive.

The Battle for the River: PG&E and the Trespassers on Their Own Land

The early 20th century brought a new kind of threat: industrialization. The burgeoning need for electricity in California led to the construction of numerous hydroelectric dams. The Pit River, with its significant flow and steep gradients, became a prime target. Pacific Gas & Electric (PG&E), a utility giant, began constructing a series of dams and powerhouses along the river, fundamentally altering its flow, impacting salmon runs, and submerging sacred sites.

The core of the Pit River Tribe’s ongoing struggle against PG&E dates back over a century. The tribe asserts that PG&E, through its extensive hydroelectric system on the Pit River and its tributaries, is illegally occupying their unceded ancestral lands. This claim is not merely historical; it is a live legal and moral battle that continues to this day.

A pivotal moment in this protracted battle occurred in the early 1970s. Frustrated by decades of ignored claims and a lack of federal action, the Pit River Tribe decided to take direct action. In 1970, tribal members, led by figures like Chairman Mickey Gemmill Sr., began to reoccupy ancestral lands, including areas near Burney and a PG&E recreation site on Hat Creek. They asserted their aboriginal title and sovereignty, declaring that they were not trespassing but reclaiming what was rightfully theirs.

"We were trying to show the world that we still exist, that this is our land," recalled a participant in the Hat Creek occupation. "They called us trespassers, but how can you trespass on your own land? We were born here, our ancestors are buried here. This is our home."

The occupations led to arrests, confrontations with law enforcement, and a landmark legal case, United States v. Pit River Tribe, where the tribe’s aboriginal title was debated in federal courts. While the courts ultimately ruled against the tribe’s claim to aboriginal title for purposes of evicting PG&E, the case brought significant national attention to their plight and highlighted the complex legal status of unceded Indigenous lands. The tribe’s legal battles against PG&E continue, evolving with PG&E’s bankruptcies and relicensing processes, always pushing for recognition, compensation, and the restoration of their lands and waters.

A Culture Forged in Resilience

Despite the relentless pressures of colonization, land dispossession, and ongoing legal battles, the Pit River Tribe has demonstrated extraordinary resilience in preserving and revitalizing its culture. Language revitalization programs are crucial, with elders working to teach the Palaihnihan languages to younger generations, recognizing that language is a direct link to their heritage and worldview.

Traditional practices continue to be a source of strength and identity. Basket weaving, a highly intricate art form passed down through generations, remains a vibrant expression of Pit River culture, with weavers using traditional materials and designs. Ceremonies and dances, though often practiced discreetly for many years, are seeing a resurgence, bringing communities together and reinforcing cultural bonds.

"Our culture is not just something from the past; it is alive," says a young tribal member involved in language classes. "It’s in the way we fish, the way we gather, the stories we tell. It’s in our connection to the river."

The tribe is also actively engaged in environmental stewardship, working to protect the remaining natural resources of their ancestral lands. Their deep traditional ecological knowledge offers invaluable insights into sustainable land and water management, insights often overlooked by mainstream environmental policies. They advocate for the health of the Pit River, recognizing that its vitality is intrinsically linked to their own.

Sovereignty and the Path Forward

Sovereignty is not an abstract concept for the Pit River Tribe; it is a lived reality, a constant assertion of their inherent right to self-governance and self-determination. They operate their own tribal government, provide services to their members, and work to build economic independence. However, like many Native American tribes, they face significant challenges, including high rates of poverty, inadequate healthcare access, and educational disparities.

Yet, amidst these formidable challenges, a deep wellspring of hope and determination persists. The tribe continues to pursue legal avenues to reclaim ancestral lands and resources, to ensure the health of the Pit River, and to protect sacred sites. They advocate for federal policies that honor tribal sovereignty and address historical injustices.

The future of the Pit River Tribe remains intrinsically linked to the land and the river that have sustained them for millennia. Their struggle is a poignant reminder that true justice often requires an unyielding heart, rooted deeply in the land it seeks to protect. As the sun sets over the rugged Modoc Plateau, casting long shadows across the Pit River, the spirit of the Ajumawi and Atsuge people remains unbroken, their voice echoing through the canyons, demanding recognition for a legacy that was never ceded, only defended. Their fight continues, a testament to the unconquered heart of California.