The Unfading Stain: Elizabeth Short and the Enduring Mystery of the Black Dahlia

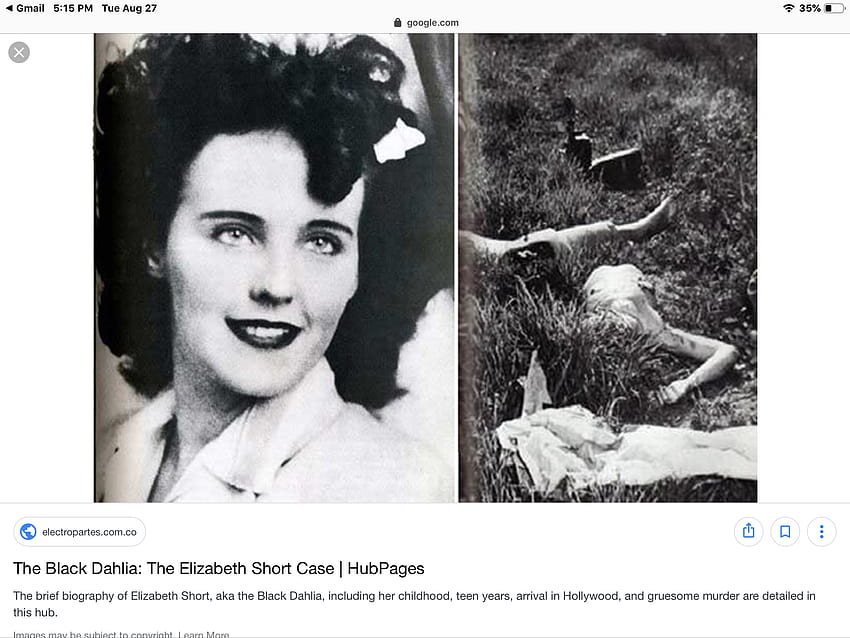

Los Angeles, January 15, 1947. The sun, usually a benevolent golden presence in Southern California, cast a harsh, unforgiving light on a vacant lot in Leimert Park. It was here, amidst weeds and discarded debris, that a young mother, out for a stroll with her child, stumbled upon a sight that would forever scar the city’s collective memory. Lying meticulously bisected at the waist, drained of blood, and grotesquely mutilated, was the body of a young woman. Her name was Elizabeth Short, but the world would soon know her by a far more chilling moniker: The Black Dahlia.

The discovery sent a jolt of horror through post-war Los Angeles, a city basking in the glow of Hollywood glamour and a burgeoning sense of optimism. But beneath the glittering facade of movie stars and palm trees, a dark undercurrent of crime and desperation pulsed. The murder of Elizabeth Short would expose this underbelly with brutal clarity, becoming an unsolved enigma that continues to haunt the annals of true crime seven decades later.

A Dreamer in the City of Angels

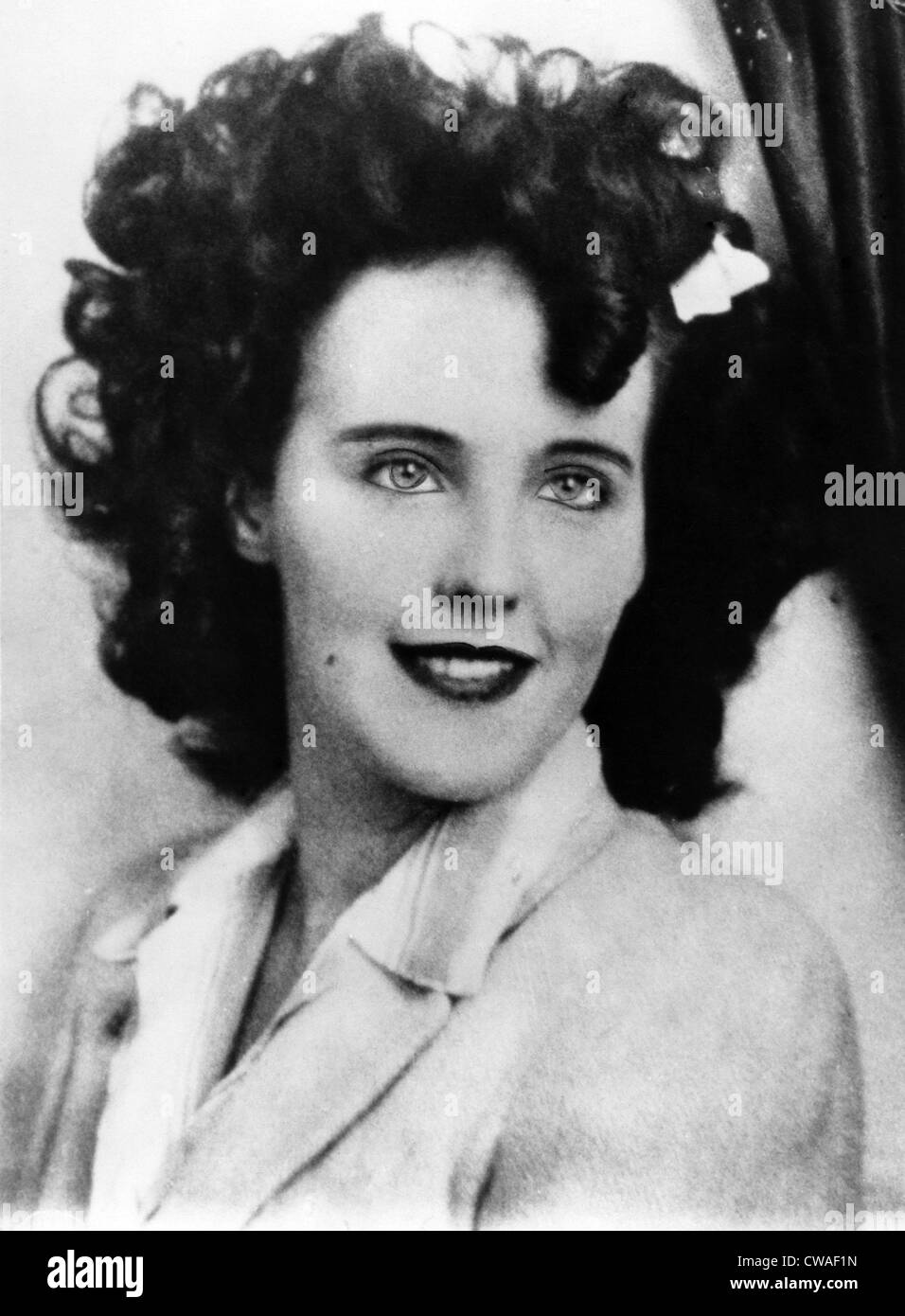

Elizabeth Short was not a starlet, though she harbored ambitions of breaking into Hollywood. Born in Boston, Massachusetts, in 1924, she was a transient spirit drawn to the West Coast’s allure like so many others of her generation. Tall, slender, with striking blue eyes and raven-black hair, she had an undeniable allure, often described as beautiful, if somewhat naive. She had worked odd jobs – a soda jerk, a waitress – and drifted between various cities before landing in Los Angeles in 1946.

Her life was far from stable. She had a history of minor arrests, mostly for underage drinking, and moved frequently, staying with acquaintances, servicemen, or in cheap hotels. Friends remembered her as someone who enjoyed attention, who loved to dance, and who often wore black, a detail that would later contribute to her macabre nickname. She had no fixed address in the weeks leading up to her death, last seen alive checking out of the Biltmore Hotel downtown on January 9th.

Her aspirations, however modest, painted a picture of a young woman seeking something more. She dreamt of acting, of escaping the mundane, and of finding her place in a world that seemed to promise endless possibilities. This yearning, common to so many who flocked to Los Angeles, made her a tragically relatable figure, her dreams cut short by an act of unimaginable savagery.

The Gruesome Tableau

Betty Bersinger, walking with her three-year-old daughter on that fateful morning, initially thought she had found a discarded mannequin. It was only upon closer inspection that the horrifying truth became apparent. The body was pristine, eerily clean, as if washed. It had been cut cleanly in half at the torso, meticulously drained of blood, and positioned with chilling precision. Her face had been slashed from the corners of her mouth to her ears, creating a grotesque, permanent smile – a "Glasgow smile." Parts of her body had been removed, and the scene was devoid of blood, suggesting she had been murdered elsewhere and then carefully transported to the lot.

The brutality was unprecedented. "It was the most shocking and gruesome crime scene I’ve ever encountered," remarked one veteran police officer at the time, a sentiment echoed by many who witnessed the horror. The level of surgical precision indicated a killer with medical knowledge or, at the very least, a chilling understanding of anatomy. The sheer theatricality of the presentation suggested a message, a deliberate act designed to shock and terrify.

The Investigation: A Labyrinth of Leads and Lies

The Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) launched an immediate and massive investigation, one of the largest in its history. Detectives Harry Hansen and Frank Perkins led the charge, faced with an overwhelming tide of public hysteria and a distinct lack of concrete evidence. The crime scene offered few clues – no weapons, no clear footprints, no significant fibers. The body had been so thoroughly cleaned that forensic analysis, rudimentary by today’s standards, yielded little.

What followed was a deluge of false confessions, crackpot theories, and frantic tips. Hundreds of individuals, ranging from the genuinely disturbed to those seeking notoriety, confessed to the murder. "Every nut in the country was confessing," one exasperated detective reportedly stated. Each confession had to be investigated, draining precious resources and time. Police interviewed thousands of people, collected countless pages of reports, but the killer remained elusive.

The case was hampered by the era’s limited forensic technology. DNA analysis was decades away. Fingerprinting was still developing. The sheer volume of incoming information, much of it useless, made finding the needle in the haystack virtually impossible. Adding to the complexity was the intense media scrutiny, which, while raising public awareness, often compromised the investigation.

The Media Frenzy and the Birth of a Legend

The murder of Elizabeth Short captivated the nation, not just Los Angeles. The press, particularly the fiercely competitive Los Angeles Herald-Express and Los Angeles Examiner, seized upon the story with an almost vampiric hunger. They sensationalized every detail, creating a feeding frenzy that both fueled public fascination and, arguably, hindered the police investigation.

It was the media that bestowed upon Elizabeth Short her infamous moniker: "The Black Dahlia." The nickname likely stemmed from her penchant for wearing black clothing and the popular 1946 film noir, The Blue Dahlia. The name stuck, transforming a real woman into a dark, enigmatic symbol. Headlines screamed, tabloids published graphic photos, and reporters vied for any scrap of information, sometimes even interfering with crime scenes or withholding details to scoop rivals.

The killer, seemingly emboldened by the attention, began to taunt the press. Letters, some composed of words cut from newspapers, others meticulously printed, arrived at newsrooms. One package contained Short’s personal effects – her birth certificate, social security card, and photographs – along with a note promising to "turn myself in on Wednesday, January 29, at 10 am. Had my fun at the police. Black Dahlia Avenger." The promise proved to be a cruel hoax, further stoking public fear and frustration. The media, in turn, published these letters, turning the killer into a macabre celebrity.

Enduring Suspects and Lingering Questions

Over the decades, countless theories and suspects have emerged, each with its proponents and detractors. The official LAPD files on the Black Dahlia case run into thousands of pages, a testament to the sheer volume of dead ends. Doctors, medical students, rejected suitors, servicemen, organized crime figures – almost anyone with a passing connection to Short, or even just a bizarre alibi, found themselves under suspicion.

Among the most prominent theories in recent years is that put forth by former LAPD homicide detective Steve Hodel, who believes his father, Dr. George Hodel, was the killer. Hodel senior was a prominent physician in Los Angeles, known for his connections to Hollywood’s elite and his bohemian lifestyle. Steve Hodel points to photographic evidence, handwriting analysis matching his father’s to the killer’s letters, and his father’s past as a suspect in other cases. While compelling, this theory, like all others, remains unproven by conclusive evidence that would stand up in court.

Other suspects have included Robert Manley, a salesman who had spent time with Short shortly before her death; Jack Anderson Wilson, a known serial killer; and even figures as disparate as Orson Welles and Woody Guthrie were briefly, and wildly, speculated upon. The lack of closure has allowed the speculation to fester, creating a fertile ground for true crime enthusiasts and amateur detectives.

A Legacy of Shadows

The Black Dahlia murder remains officially unsolved, a permanent stain on the LAPD’s record and a grim reminder of the limitations of justice. Elizabeth Short’s brutal death transcended a mere crime; it became a cultural phenomenon, a dark archetype of Hollywood’s underbelly, and a cautionary tale of dreams gone awry.

Her story has been retold countless times in books, films (most notably Brian De Palma’s 2006 adaptation of James Ellroy’s novel), documentaries, and TV shows. It continues to inspire artists, writers, and true crime enthusiasts, drawn to its potent mix of glamour, depravity, and an enduring mystery. The case is often cited as a benchmark for unsolved homicides, a symbol of the perfect crime – or perhaps, simply a victim of its time, when forensic science was in its infancy and media sensationalism could easily derail an investigation.

Elizabeth Short, the young woman with black hair and a yearning for a different life, lies buried in an Oakland cemetery, her final resting place far from the Hollywood lights she once chased. Her memory, however, remains inextricably linked to the chilling nickname and the horrifying manner of her death. The Black Dahlia case is more than just a cold case; it is a permanent fixture in the dark mythology of Los Angeles, a city forever haunted by the ghost of a dream that turned into a nightmare. The question of who killed Elizabeth Short lingers, an unfading stain on the fabric of American crime, a testament to a mystery that refuses to die.