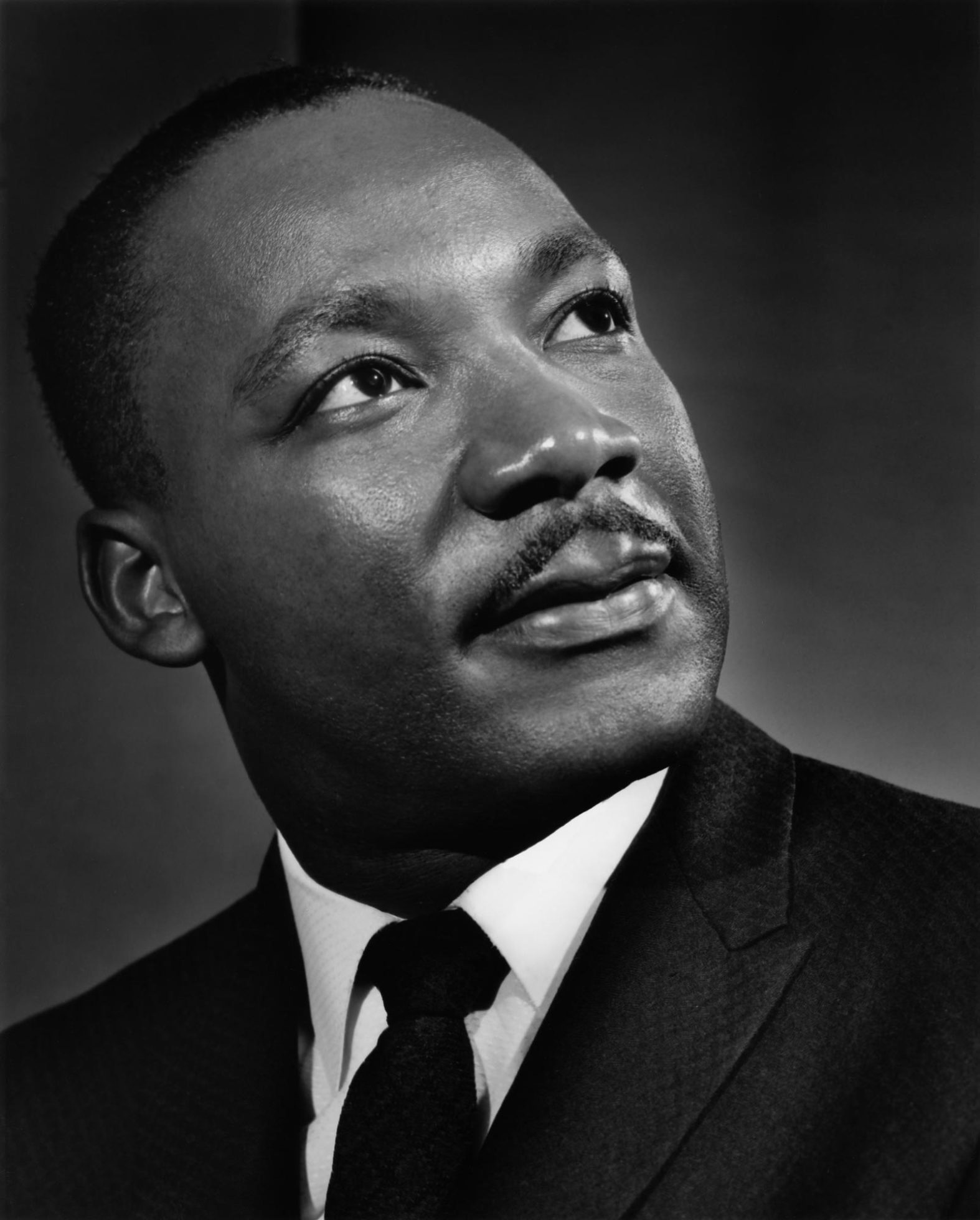

The Unfinished Symphony: Martin Luther King Jr.’s Enduring Dream

On August 28, 1963, before a quarter of a million people gathered on the National Mall, a voice resonated from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, painting a vision of a nation transformed. "I have a dream," declared Martin Luther King Jr., "that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character." It was a moment etched into the annals of history, a rhetorical crescendo that crystallized the aspirations of a generation and continues to echo through the corridors of time. Yet, to reduce King to this singular, iconic speech is to miss the complexity, the unwavering courage, and the profound strategic genius of a man who, in a tragically short life, fundamentally reshaped America and inspired movements for justice worldwide.

Born Michael King Jr. in Atlanta, Georgia, on January 15, 1929, he later adopted the name Martin Luther in homage to the Protestant Reformation leader. His upbringing in the heart of the Jim Crow South, as the son of a prominent Baptist minister, immersed him early in the realities of racial segregation and the spiritual sanctuary of the Black church. This dual exposure – the sting of injustice and the solace of faith – would define his path. Educated at Morehouse College, Crozer Theological Seminary, and Boston University, where he earned his Ph.D. in systematic theology, King was intellectually rigorous, a scholar deeply versed in philosophy, history, and the social gospel. He drew heavily from the nonviolent philosophy of Mahatma Gandhi, believing that moral force, rather than physical aggression, was the most potent weapon against oppression.

King’s emergence onto the national stage was less a calculated career move and more a reluctant calling thrust upon him by circumstance. In December 1955, a seamstress named Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a Montgomery, Alabama, bus to a white passenger, sparking a city-wide boycott. The local Black community, seeking a leader for their burgeoning movement, turned to the young, articulate pastor of Dexter Avenue Baptist Church. At just 26 years old, King found himself at the helm of the Montgomery Bus Boycott, a 381-day struggle that tested the resolve of an entire community. His leadership, characterized by fervent oratory and an unshakeable commitment to nonviolence, transformed a local protest into a pivotal moment in the Civil Rights Movement. The Supreme Court’s ruling desegregating public transportation in Montgomery validated the movement’s strategy and catapulted King into the national spotlight as the voice of a burgeoning, nonviolent revolution.

The success in Montgomery led to the formation of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) in 1957, with King as its first president. This organization became the primary vehicle for his nonviolent direct action campaigns across the South. The years that followed were a relentless crucible of sit-ins, freedom rides, and mass protests, each designed to expose the brutality of segregation and force federal intervention. King understood that for moral suasion to work, the injustice had to be visible and undeniable. "We must use time creatively," he famously wrote, "in the knowledge that the time is always ripe to do right."

One of the most perilous and strategically crucial campaigns unfolded in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1963. Known as "Bombingham" due to its history of racial violence, the city was a bastion of segregation. King’s decision to confront its notorious police chief, Bull Connor, was a high-stakes gamble. The images of peaceful demonstrators, including children, being attacked by police dogs and fire hoses shocked the nation and the world, exposing the raw, ugly face of racism. It was during his imprisonment in Birmingham that King penned his seminal "Letter from a Birmingham Jail," a powerful defense of nonviolent civil disobedience, articulating why direct action was necessary to create "a crisis-packed situation that will inevitably open the door to negotiation." This letter, smuggled out of jail and widely published, became a foundational text for the movement, rebuking white moderates who prioritized order over justice.

The Birmingham campaign, despite its harsh repression, proved to be a turning point, galvanizing public opinion and paving the way for the March on Washington later that summer. The "I Have a Dream" speech, delivered on that sweltering August day, was not merely an eloquent plea for racial equality but a masterful articulation of America’s unfulfilled promise, framed within the nation’s founding ideals. It was a call to live up to the "magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence."

The momentum generated by these campaigns bore fruit in landmark legislation. The Civil Rights Act of 1964, signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson, outlawed segregation in public places and discrimination in employment. The following year, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 dismantled discriminatory voting practices that had disenfranchised Black Americans for generations. These were monumental achievements, direct results of the sacrifices made by King and countless other activists. King himself was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964, becoming the youngest recipient at 35, a testament to his global impact.

However, King understood that legal victories, while essential, were not enough. As the movement moved north, it confronted de facto segregation, economic inequality, and systemic poverty that were more deeply entrenched and less amenable to simple legislative fixes. His focus broadened to encompass economic justice for all, regardless of race. He launched the Poor People’s Campaign, aiming to unite a multi-racial coalition of impoverished Americans to demand economic rights. "What good is it to be able to eat at a lunch counter," he asked, "if you can’t afford a hamburger?"

King’s moral compass also led him to oppose the Vietnam War, a stance that alienated some of his allies, including President Johnson, and drew criticism from both conservatives and some within the Civil Rights Movement who feared it would dilute their message. Yet, King saw the interconnectedness of injustice, arguing that the resources squandered on war could be used to alleviate poverty at home and that the war disproportionately affected poor Americans and people of color. "A nation that continues year after year to spend more money on military defense than on programs of social uplift," he declared, "is approaching spiritual death."

His final years were marked by escalating threats, FBI surveillance, and the growing frustration of a movement facing increasingly complex challenges. The rise of Black Power, while offering a different approach to racial liberation, also highlighted internal tensions within the broader movement, though King consistently maintained his commitment to nonviolence.

On April 4, 1968, while in Memphis, Tennessee, to support striking sanitation workers, Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel. His death sent shockwaves across the globe, igniting riots in cities across America and plunging the nation into profound grief. The "dreamer" had been silenced, but his dream, though bruised and battered, lived on.

The legacy of Martin Luther King Jr. is an unfinished symphony, a testament to both profound progress and persistent struggle. His words and actions continue to inspire movements for human rights, democracy, and social justice in every corner of the world. The annual celebration of Martin Luther King Jr. Day serves as a national reminder not only of his extraordinary contributions but also of the ongoing work required to realize his vision of a "Beloved Community" – a society founded on justice, equality, and love.

Fifty years on, the United States has made undeniable strides, with greater legal equality and opportunities for people of color. Yet, systemic racism persists in various forms, from economic disparities and mass incarceration to educational inequities and health care access. The fight against prejudice, poverty, and militarism, the "triple evils" King identified, remains a pressing concern. His life reminds us that true progress demands unwavering moral courage, strategic action, and a persistent faith in the possibility of a more just world. As King himself articulated, "The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice." His enduring dream serves as both a comfort and a challenge, a beacon guiding humanity towards the difficult, yet essential, work of building a society where character, not color, truly defines every individual.