The Unfired Volley: How the Wakarusa War Forged Bleeding Kansas

In the annals of American history, the years leading up to the Civil War are often painted in broad strokes of political rhetoric, legislative battles, and the looming threat of disunion. Yet, beneath this grand narrative, a smaller, more intimate conflict simmered and erupted on the Kansas frontier, a brutal dress rehearsal for the national catastrophe to come. This was "Bleeding Kansas," a period of intense violence and ideological warfare, and its opening act, the Wakarusa War of November-December 1855, stands as a pivotal, if often overlooked, chapter. It was a war that, paradoxically, saw little actual combat but solidified the lines of division, galvanized partisans, and irrevocably set the stage for escalating bloodshed.

To understand the Wakarusa War, one must first grasp the explosive context of Kansas Territory in the mid-1850s. The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, championed by Senator Stephen A. Douglas, was designed to resolve the contentious issue of slavery in new territories by introducing the principle of "popular sovereignty." This meant the residents of each territory would decide for themselves whether to allow slavery. The Act simultaneously repealed the Missouri Compromise of 1820, which had prohibited slavery north of the 36°30′ parallel, thus throwing open vast new lands to potential slaveholding.

The repeal of the Missouri Compromise was akin to striking a match in a powder keg. For abolitionists and Free-Staters (those who opposed the expansion of slavery), it was an outrageous concession to the slaveholding South. For pro-slavery advocates, particularly those in neighboring Missouri, it represented an opportunity to secure Kansas as a slave state, protecting their peculiar institution and expanding its influence. The result was a desperate race for settlement, transforming Kansas into a battleground for the very soul of the nation.

Settlers poured into Kansas from both sides of the divide. From the North came emigrants, often subsidized by organizations like the New England Emigrant Aid Company, armed with Bibles, rifles, and a fervent belief in free labor. From the South, especially western Missouri, came "Border Ruffians"—armed pro-slavery men, often crossing the border merely to vote illegally, intimidate Free-Staters, and enforce their will through violence. These two groups, diametrically opposed in their vision for Kansas, were on an inevitable collision course.

The Spark: A Murder and a Rescue

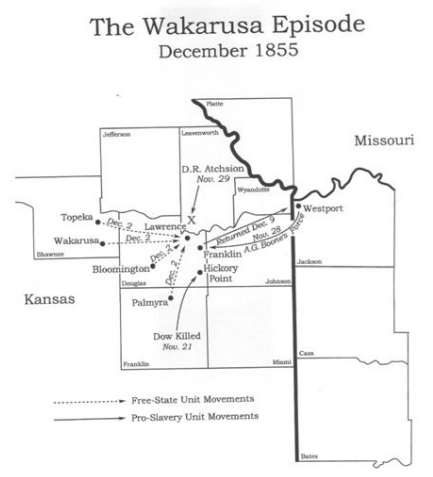

The immediate catalyst for the Wakarusa War was a seemingly minor dispute that quickly escalated into a territorial crisis. On November 21, 1855, near Hickory Point, a pro-slavery settler named Franklin Coleman shot and killed Charles Dow, a Free-State man, over a land claim dispute and a perceived insult. While Coleman claimed self-defense, Free-Staters viewed it as an unprovoked murder.

The local pro-slavery sheriff, Samuel J. Jones, based in the pro-slavery stronghold of Douglas County (near present-day Lecompton), attempted to arrest a Free-State neighbor of Dow’s, Jacob Branson, for alleged complicity in the dispute. However, as Jones transported Branson, a group of Free-Staters, led by James H. Lane and Samuel N. Wood, ambushed the sheriff and his posse, freeing Branson and spiriting him away to the Free-State bastion of Lawrence.

Sheriff Jones, humiliated and enraged, saw this act as an open rebellion against legitimate authority. He immediately appealed to Territorial Governor Wilson Shannon for assistance, claiming that Lawrence was in open revolt and calling for a substantial militia to help him enforce the law. Governor Shannon, a Democrat appointed by President Franklin Pierce, found himself in an impossible position, caught between the increasingly volatile factions. Unsure of the true extent of the "rebellion," but under immense pressure from pro-slavery elements, Shannon reluctantly authorized the formation of a territorial militia.

The Gathering Storm: An Army on the Plains

News of the events spread like wildfire. To the Free-Staters, Jones’s call for a militia was merely a pretext for pro-slavery forces to invade and destroy Lawrence, the symbolic heart of their movement. To the pro-slavery forces, Branson’s rescue and the perceived defiance of Lawrence were intolerable challenges to their authority and vision for Kansas.

Within days, thousands of armed men converged on the Wakarusa River valley, just south of Lawrence. From Missouri streamed Border Ruffians, often heavily armed, many wearing distinctive blue shirts, and eager for a fight. They established camps, most notably Fort Saunders, on the high ground overlooking the Free-State town. Estimates of their numbers vary, but it is believed that between 1,500 and 2,500 pro-slavery men gathered, vastly outnumbering the defenders of Lawrence. Among them were prominent pro-slavery leaders like David Rice Atchison, a former U.S. Senator from Missouri, who openly encouraged the men to "send every scoundrel of them back to where he came from, or into hell."

Lawrence, meanwhile, braced for the assault. Under the leadership of Free-State governor-elect Charles Robinson and the charismatic, if controversial, James H. Lane, the town quickly erected makeshift defenses. Stone barricades were thrown up, trenches dug, and settlers armed themselves with whatever they could find—hunting rifles, pistols, and even farming implements. Men, women, and children worked feverishly to fortify their homes and prepare for the inevitable. Though numbering perhaps only 500-800 effective fighting men, the Free-Staters were united by a fierce determination to defend their homes and their vision for Kansas.

The stage was set for a bloody confrontation. For nearly two weeks, the two armed camps faced each other across the frozen prairie. The air crackled with tension, punctuated by sporadic skirmishes, taunts, and the occasional exchange of gunfire. Both sides knew that a full-scale battle could unleash unimaginable carnage. Yet, amidst the fervent preparations and the bluster, a crucial element was missing: a decisive order to attack.

The Unfired Volley: A Tense Stand-off

Despite the overwhelming numerical superiority of the pro-slavery forces, and their stated intent to "exterminate" Lawrence, a full-scale assault never materialized. Several factors contributed to this uneasy stalemate. Governor Shannon, despite his initial misjudgment, became increasingly alarmed by the sheer scale of the pro-slavery forces and the potential for a catastrophic loss of life. He realized that a full-blown attack on Lawrence would be a massacre, staining his administration and potentially igniting a national civil war even sooner.

Shannon desperately sought to mediate a peaceful resolution. He met with leaders from both sides, including Robinson and Lane from Lawrence, and Atchison and other pro-slavery figures from the militia camps. The Free-State leaders, while defiant, were also pragmatic. They understood their numerical disadvantage and the terrible cost of an open battle. Their primary goal was to ensure the safety of Lawrence and prevent the imposition of pro-slavery law by force.

On December 8, 1855, after intense negotiations, an agreement was finally reached. The "Treaty of Wakarusa," as it became known, was a fragile truce. In exchange for the disbandment of the pro-slavery militia, Governor Shannon pledged to investigate the Dow murder, protect Lawrence from further attacks, and release any Free-Staters held by the pro-slavery forces. The Free-State leaders, for their part, agreed to cooperate with legal processes and to disarm their own forces.

The Wakarusa War officially ended with the dispersal of the militias. Casualties were remarkably low for such a large-scale confrontation—only one Free-Stater and one pro-slavery man were killed in minor skirmishes, and a pro-slavery man was accidentally killed by friendly fire. However, the human cost was not measured solely in lives lost. The psychological toll, the fear, the disruption, and the hardening of animosities were immense.

Echoes of War: The Legacy of Wakarusa

While the Wakarusa War averted a major battle, its impact on Bleeding Kansas and the national trajectory was profound. It proved to be a critical turning point, not in ending the violence, but in accelerating it and defining its terms.

- Failure of Popular Sovereignty: The war starkly demonstrated that popular sovereignty, in practice, was a recipe for chaos and violence, not peaceful democratic resolution. The federal government, through Governor Shannon, had shown its inability to control the situation, ceding de facto authority to armed militias.

- Radicalization of Both Sides: The near-confrontation further hardened the resolve of both Free-Staters and pro-slavery advocates. For Free-Staters, it was a confirmation that they could only rely on themselves for defense against what they perceived as an invading force. For many pro-slavery men, it fueled a sense of grievance and a desire for retribution against the "rebellious" Free-Staters.

- Rise of Militancy: The Wakarusa War directly preceded and arguably influenced the actions of more extreme figures. John Brown, who had arrived in Kansas earlier in 1855, saw the events at Wakarusa as further proof that only armed struggle could secure freedom. His infamous Pottawatomie Massacre in May 1856, a brutal retaliatory killing of five pro-slavery settlers, was a direct response to the escalating violence and the Sack of Lawrence (which occurred shortly before Pottawatomie, illustrating the rapid escalation post-Wakarusa). The Sack of Lawrence, where pro-slavery forces ransacked and burned buildings, was another unpunished act of aggression that showed the Wakarusa truce was merely a pause.

- National Attention: The Wakarusa War, though bloodless in comparison to later events, drew significant national attention to Kansas. Newspapers across the country reported on the brink of civil war in the territory, further polarizing public opinion and fueling the growing sectional divide. The image of two armed camps facing each other, ready to fight over the future of slavery, became a powerful symbol of America’s deepening crisis.

In essence, the Wakarusa War was a moment of profound revelation. It exposed the raw, visceral hatred that simmered beneath the surface of American society. It showed that the issue of slavery was no longer a matter for polite debate or legislative compromise, but a fundamental conflict that people were willing to kill and die for. It established Lawrence as a symbol of Free-State resistance and a repeated target, and it transformed Kansas into the crucible where the future of the nation was being violently forged.

The Wakarusa War, an "unfired volley" that nonetheless echoed across the continent, stands as a testament to the fact that wars are not always defined by their body count. Sometimes, the threat of violence, the mobilization of armies, and the hardening of ideological lines can be just as significant in shaping history as any bloody battle. It was a war that, by not truly fighting, ensured that far bloodier conflicts would inevitably follow, paving the grim road to Fort Sumter and the American Civil War.