The Unflinching Eye: Charles Carroll Goodwin and the Forging of America’s Legends

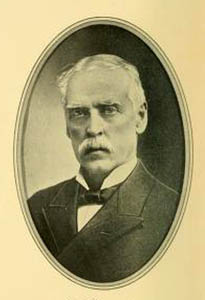

America, a nation born of revolution and built on a vast, untamed continent, is as rich in legends as it is in history. From the towering figures of the Founding Fathers to the mythical beasts of the wilderness, from the heroic deeds of frontier pioneers to the spectral tales whispered in shadowed valleys, these narratives form the bedrock of the national psyche. Yet, legends are not born in a vacuum; they emerge from the crucible of lived experience, amplified by storytellers, and solidified by the collective imagination. Few stood closer to this fascinating process than Charles Carroll Goodwin, a journalist, editor, and author whose keen eye and sharp pen captured the raw material of American myth-making as it unfolded in the tumultuous 19th-century West.

Goodwin was not a mythmaker in the traditional sense, crafting fanciful tales from whole cloth. Rather, he was an observer, a chronicler of an era so dynamic, so fraught with peril and promise, that its everyday realities often bordered on the legendary. As editor of the Carson Appeal and later the Virginia City Daily Territorial Enterprise – two pivotal newspapers in the heart of the Comstock Lode – Goodwin was positioned at the epicenter of one of America’s most dramatic sagas: the silver rush that transformed a desolate Nevada landscape into a roaring engine of wealth and human ambition. His work offers a unique window into how the grit, grandeur, and occasional madness of the American West were transmuted into enduring legends.

The Comstock Lode itself, discovered in 1859, was a legend in the making. It wasn’t just a silver strike; it was a phenomenon that drew prospectors, engineers, gamblers, prostitutes, poets, and desperadoes from across the globe. Overnight, boomtowns like Virginia City sprung up, teeming with a volatile mix of hope and desperation. This was Goodwin’s beat. He reported on the dizzying fortunes made and lost, the subterranean struggles of miners battling heat and rock, the cutthroat politics, and the vibrant, often violent, social fabric of a society being forged anew.

Goodwin’s journalism, characterized by its detailed observations and often wry commentary, served as a primary source for understanding this epic period. He documented the lives of the "bonanza kings" – figures like John Mackay, James Fair, James Flood, and William O’Brien – whose rags-to-riches stories became archetypes of American opportunity. These men, through sheer will, luck, and shrewd business acumen, amassed fortunes that rivaled European royalty. Their lives, filled with spectacular successes and bitter rivalries, were the stuff of immediate legend, broadcast daily by papers like Goodwin’s. He saw the transformation of ordinary men into titans, and in doing so, he recorded the genesis of a fundamental American legend: that of limitless possibility and the self-made man.

Beyond the magnates, Goodwin chronicled the everyday heroes and anti-heroes of the Comstock: the tireless miners who risked their lives in sweltering depths, the tenacious pioneer women who built homes in the wilderness, and the colorful rogues whose escapades added spice to the frontier narrative. He was there when Mark Twain, then Samuel Clemens, was honing his literary voice at the Territorial Enterprise, sharing the same newsroom and perhaps even contributing to the vibrant, exaggerated style that would become synonymous with frontier storytelling. Twain, of course, would become a legend himself, and his early experiences in the West, documented and shared by his contemporaries, laid the groundwork for his later iconic works.

In his seminal work, The Comstock Lode: America’s First Great Mining Bonanza (1900), Goodwin offered a retrospective, detailed account of the era he witnessed. This book, while a work of history, is permeated with the spirit of legend. He doesn’t just list facts; he paints vivid pictures, recounts anecdotes, and evokes the larger-than-life atmosphere that defined the Comstock. For instance, he details the engineering marvels of the mining shafts, the immense wealth extracted, and the sheer human effort involved, all of which contributed to the almost mythical scale of the endeavor. He describes the vast underground networks, the dangerous "fire damp" explosions, and the incredible heat, turning the mundane act of mining into an epic struggle against nature itself.

Goodwin understood that legends often emerge from the collision of human ambition with the unforgiving forces of nature. The West was a canvas for such collisions. The vastness of the landscape, the extremes of weather, and the sheer physical challenge of carving out a civilization all contributed to a sense of the heroic. The tall tales of Pecos Bill or Paul Bunyan, while often attributed to later periods, drew their spirit from the kind of exaggeration and larger-than-life experiences that Goodwin would have encountered daily. The need to make sense of an incomprehensible new world, to tame its terrors and celebrate its triumphs, fostered a fertile ground for such narratives.

But it wasn’t just the heroic or the industrious that became legendary. The West was also a crucible of lawlessness, and its outlaws and lawmen also etched themselves into the national consciousness. While figures like Billy the Kid and Jesse James operated in different territories, the archetype of the gunslinger and the quick-draw justice (or injustice) was a pervasive element of the frontier. Goodwin, in his reporting, would have covered local skirmishes, duels, and the struggles of nascent legal systems to impose order. These factual accounts, stripped of their immediate context and romanticized over time, became the basis for countless Western legends. The newspaper, in this sense, was not merely a recorder of events but an active participant in shaping public perception, inadvertently laying the groundwork for future mythologies.

Consider the legend of the "ghost town." Goodwin saw these towns in their infancy and their full, vibrant bloom. He also witnessed their decline as veins of ore ran dry or markets shifted. The rapid abandonment of once-thriving communities left behind silent streets and decaying buildings, fertile ground for tales of lingering spirits, lost fortunes, and the ephemeral nature of human endeavor. Goodwin’s descriptions of the Comstock’s boom-and-bust cycle provide the historical underpinning for these later, more spectral legends. He saw the lifeblood drain from a place, setting the stage for the whispers of what might have been.

One of the fascinating aspects of Goodwin’s journalistic approach was his commitment to documenting the truth as he saw it, even as that truth was often stranger and more dramatic than fiction. He did not intentionally spin yarns, but his precise, detailed reporting of extraordinary events and characters naturally lent itself to the creation of legend. As historian Frederick Jackson Turner famously argued, the American frontier was a crucible that forged a unique national character—independent, resourceful, and democratic. Goodwin’s writings provide empirical evidence of this forging process, showing how the challenges and opportunities of the frontier shaped individuals and, by extension, the collective American narrative.

In a broader sense, Goodwin’s work illuminates how American legends differ from those of older civilizations. While European legends often involve ancient kings, mythical beasts, or divine interventions, American legends frequently center on human agency, ingenuity, and the struggle against a vast, indifferent wilderness. They celebrate the individual’s ability to overcome immense obstacles, to carve out a destiny, and to transform the landscape. Goodwin’s accounts of the mining frontier are a testament to this spirit—a spirit that saw men tunnel miles into the earth, endure unimaginable conditions, and build cities overnight, all driven by the promise of wealth and the allure of the unknown.

In conclusion, Charles Carroll Goodwin, the journalist of the Comstock Lode, was a crucial, albeit unintentional, architect of American legends. Through his unflinching eye and diligent reporting, he captured the raw, visceral reality of the 19th-century American West, a reality so potent and dramatic that it could not help but evolve into myth. He chronicled the rise of self-made titans, the epic struggle against nature, the boom-and-bust cycles of fortune, and the vibrant, often chaotic, society that gave birth to enduring archetypes. His detailed accounts, far from being mere dry historical records, provide the factual bedrock upon which the rich tapestry of American legends is woven. They remind us that legends are not just stories from a distant past but living narratives, constantly being shaped by human experience, and forever rooted in the extraordinary truths witnessed by those who, like Goodwin, stood at the very moment of their making. His legacy is a testament to the idea that sometimes, the most compelling legends are simply the truth, well-observed and powerfully told.