The Unfolding Tragedy: Native American Timelines in the Shadow of Westward Expansion

The narrative of American westward expansion is often painted with broad strokes of heroism and progress, a saga of pioneers conquering a vast, untamed wilderness. Yet, beneath this romanticized veneer lies a far more complex and often tragic reality – a story of profound displacement, broken treaties, and cultural destruction for the Indigenous peoples who had inhabited these lands for millennia. This journalistic exploration delves into the Native American timeline during westward expansion, illuminating the resilience, resistance, and devastating losses experienced by these First Nations as a continent was reshaped.

A Continent Thriving: Before the European Tide

Long before the concept of "westward expansion" even existed, the North American continent was a mosaic of diverse, thriving Indigenous civilizations. From the sophisticated agricultural societies of the Mississippian Mound Builders in the Southeast to the intricate Pueblo communities of the Southwest, the nomadic hunter-gatherers of the Great Plains, and the sophisticated fishing cultures of the Pacific Northwest, an estimated 2 to 18 million people lived in harmony with the land, developing complex political structures, rich spiritual traditions, and sustainable economies.

For example, the Iroquois Confederacy in the Northeast, established centuries before European contact, featured a democratic system that influenced the framers of the U.S. Constitution. On the Great Plains, tribes like the Lakota, Cheyenne, and Comanche had developed a profound relationship with the buffalo, which provided sustenance, shelter, and spiritual meaning. These were not empty lands awaiting discovery, but vibrant, interconnected worlds.

The initial European arrival in the late 15th and 16th centuries brought not just new technologies and ideas, but also devastating diseases like smallpox, measles, and influenza, against which Native populations had no immunity. Historians estimate that up to 90% of some Indigenous populations perished in the initial waves of epidemics, profoundly weakening societies even before widespread conflict over land began. This biological catastrophe laid a grim foundation for the centuries of interaction to come.

The Dawn of a New Nation: Land Hunger and "Civilization"

With the birth of the United States in 1776, the fledgling nation immediately cast its eyes westward. The vast lands beyond the Appalachian Mountains, largely inhabited by various Indigenous nations, became the object of intense desire for an expanding population. Early federal policy, particularly under President Thomas Jefferson, adopted a dual approach: while speaking of "civilizing" Native Americans by encouraging them to adopt farming, Christianity, and private land ownership, it simultaneously pursued their removal to make way for white settlers.

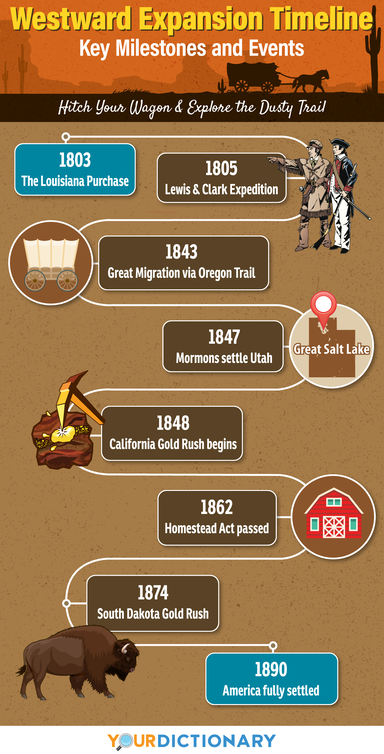

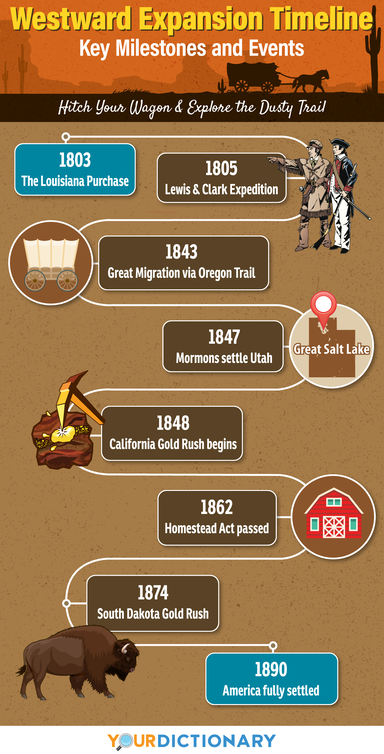

The Louisiana Purchase of 1803, a monumental acquisition from France, dramatically expanded U.S. territory, effectively doubling its size overnight. Crucially, this purchase was made without any consultation or recognition of the Indigenous peoples who held ancestral claims to these lands. It was a transaction between European powers that completely disregarded the sovereignty of nations like the Osage, Pawnee, and Sioux, setting a dangerous precedent for future land grabs.

Jefferson’s vision, though seemingly benevolent in its "civilization" rhetoric, was inherently predicated on the idea that Native cultures were inferior and must be changed or removed. He famously wrote in 1803 that Native Americans could "live in peace and plenty," but only if they "will give up hunting, and live by labour as we do." The implicit threat was clear: adapt or move.

The Era of Forced Removal: "Trail of Tears" and Beyond

The early 19th century witnessed the most egregious act of state-sponsored ethnic cleansing in American history: the forced removal of the "Five Civilized Tribes" – the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole – from their ancestral lands in the southeastern United States. These tribes had, ironically, largely adopted many aspects of American culture, including writing systems (the Cherokee Syllabary invented by Sequoyah), constitutional governments, and farming practices. They were, by all accounts, sovereign nations with established treaties with the U.S. government.

However, their lands lay in the path of the burgeoning cotton kingdom, and the discovery of gold in Cherokee territory intensified settler and state government demands for their removal. Despite the Supreme Court ruling in Worcester v. Georgia (1832), which affirmed Cherokee sovereignty and invalidated Georgia’s laws over their territory, President Andrew Jackson famously defied the decision, reportedly sneering, "John Marshall has made his decision; now let him enforce it."

The Indian Removal Act of 1830, championed by Jackson, authorized the forced displacement of these tribes to lands west of the Mississippi River, in what is now Oklahoma. Between 1830 and 1850, tens of thousands of Native Americans were forcibly marched from their homes. The most infamous was the Cherokee’s "Trail of Tears" in 1838-39, a brutal winter march where over 4,000 of the 16,000 Cherokees died from disease, starvation, and exposure. Private John G. Burnett, a soldier who participated in the removal, later recalled, "I saw the helpless Cherokees arrested and dragged from their homes… I saw them loaded like cattle or sheep into six hundred and forty-five wagons and started toward the west." This event stands as a stark testament to the U.S. government’s willingness to violate its own laws and moral principles in pursuit of land.

Manifest Destiny and the Western Front

As the nation pushed further west, the ideology of "Manifest Destiny" took hold. Coined in 1845 by journalist John L. O’Sullivan, it asserted America’s divinely ordained right, even duty, to expand its dominion and spread democracy across the North American continent "from sea to shining sea." This powerful, often racist, belief provided a moral justification for territorial expansion, economic exploitation, and the displacement of Indigenous peoples.

The discovery of gold in California in 1848 triggered a massive influx of settlers, forever altering the landscape and escalating conflicts. The Homestead Act of 1862 further incentivized westward migration, offering 160 acres of "free" land to settlers – land that was, in reality, almost universally occupied by Native Americans. The construction of the Transcontinental Railroad, beginning in the 1860s, tore through Indigenous territories, bringing more settlers, resources, and environmental destruction, particularly to the vast buffalo herds of the Great Plains.

The Plains tribes, including the Lakota, Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Comanche, were among the last to experience the full force of this expansion. Their nomadic way of life, centered around the buffalo, was directly threatened by settler encroachment, railroad construction, and the deliberate slaughter of the buffalo.

The Plains Wars and the Reservation System

The period from the 1850s to the late 1880s was marked by intense and brutal conflicts known as the Plains Wars. As settlers encroached on Native hunting grounds and sacred sites, resistance flared. Key battles and massacres dotted the landscape:

- Sand Creek Massacre (1864): U.S. troops attacked a peaceful encampment of Cheyenne and Arapaho, killing over 150, mostly women and children, despite a white flag being flown.

- Fetterman Fight (1866): Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho warriors ambushed and annihilated a U.S. Army detachment, a significant victory for Native forces.

- Battle of Little Bighorn (1876): A stunning defeat for the U.S. Army, where Lakota and Cheyenne warriors, led by Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse, annihilated General George Custer’s 7th Cavalry. This victory, however, was short-lived and only intensified the government’s resolve.

A critical, and devastating, strategy employed by the U.S. military was the deliberate extermination of the American bison (buffalo). From an estimated 30-60 million in the early 19th century, the buffalo population plummeted to a few hundred by the end of the century. This was not merely a consequence of hunting; it was a calculated military tactic to destroy the primary food source and cultural bedrock of the Plains tribes, forcing them into dependency and onto reservations. As General Philip Sheridan stated, "Let them kill, skin, and sell until the buffalo is exterminated, as it is the only way to bring lasting peace and allow civilization to advance."

The reservation system, initially conceived as a way to separate and "protect" Native Americans, quickly became a tool of control and impoverishment. Tribes were confined to small, often unproductive parcels of land, breaking their traditional social structures, economies, and spiritual connections to the wider landscape. Their sovereignty was severely curtailed, and they were subjected to paternalistic federal oversight.

One of the most poignant examples of this era is Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce, who led his people on an epic 1,170-mile flight in 1877, attempting to escape forced removal to a reservation. His surrender speech remains a powerful testament to the futility of resistance against overwhelming odds: "Hear me, my chiefs! I am tired; my heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands, I will fight no more forever."

Assimilation and the Dawes Act

Even as physical resistance waned, the U.S. government launched a new assault: cultural assimilation. The philosophy was encapsulated in the grim phrase, "Kill the Indian, save the man." Policies aimed at eradicating Indigenous languages, religions, and traditions were implemented.

Boarding schools, such as the infamous Carlisle Indian Industrial School, became a primary tool. Native children, often forcibly removed from their families, had their hair cut, were forbidden to speak their native languages, and were taught vocational skills and Christian values. The trauma inflicted by these schools, designed to strip children of their cultural identity, reverberates through generations today.

The General Allotment Act, or Dawes Act, of 1887, was another devastating blow. It aimed to break up communally held tribal lands into individual plots, believing that private land ownership would "civilize" Native Americans. "Surplus" land – often the most valuable – was then sold off to non-Native settlers. The result was a catastrophic loss of land for Native Americans: from about 150 million acres in 1887, their land holdings shrunk to just 48 million acres by 1934. It further fragmented tribal communities and undermined their collective power.

Wounded Knee and the End of an Era

The final tragic chapter of this era of armed conflict came at Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota, in December 1890. Fearful of the Ghost Dance movement, a spiritual revival that promised a return of Native ways and the buffalo, U.S. troops confronted a band of Lakota Sioux. A shot was fired – its origin disputed – and the soldiers opened fire, killing an estimated 300 unarmed Lakota, including many women and children. This massacre effectively marked the end of major armed resistance by Native Americans to U.S. expansion.

Legacy and Resilience

The legacy of westward expansion for Native Americans is one of profound trauma, dispossession, and systemic inequality. Generations have grappled with the intergenerational effects of forced removal, cultural suppression, and economic marginalization. Poverty, health disparities, and historical trauma continue to challenge Indigenous communities.

Yet, the story does not end there. Despite centuries of concerted effort to erase them, Native American nations have demonstrated extraordinary resilience. Today, 574 federally recognized tribes in the United States continue to fight for sovereignty, self-determination, and the revitalization of their cultures and languages. Movements like the Standing Rock Sioux’s resistance to the Dakota Access Pipeline underscore the ongoing struggle for land, water, and treaty rights.

Understanding the true Native American timeline of westward expansion requires confronting the uncomfortable truths of American history. It demands acknowledging that the "progress" of one group often came at the catastrophic expense of another. As the historian Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz aptly states, "The United States is a colonial settler-state, founded on the doctrine of discovery and built on the dispossession of Indigenous peoples." Only by grappling with this complex, painful history can a path forward be forged, one that honors the enduring presence, contributions, and sovereignty of America’s First Nations.