The Unlikely Oasis: Camp Ewing and Kansas’s Forgotten WWII Secret

The vast, golden plains of Kansas, stretching endlessly beneath an immense sky, are synonymous with agriculture, the heartland of America, and a quiet, unassuming way of life. It is a landscape that whispers of wheat fields, pioneer spirit, and perhaps, the gentle hum of small-town existence. Yet, nestled near the city of Liberal, in the southwest corner of this quintessential American state, lies the spectral memory of a chapter in history that defies the pastoral image: Camp Ewing, a sprawling prisoner of war (POW) camp that, for a crucial period during World War II, housed thousands of captured Axis soldiers, turning a corner of the prairie into an unlikely and often misunderstood oasis of wartime diplomacy and unexpected humanity.

The very notion of a German or Italian soldier, captured on the battlefields of North Africa or Europe, finding themselves tilling sugar beet fields in Kansas, seems almost surreal. But as the tide of World War II turned against the Axis powers, the sheer volume of captured enemy personnel presented the Allied forces with a logistical challenge. Britain, already stretched thin by the war effort and facing the constant threat of invasion, couldn’t accommodate the influx of prisoners. The United States, with its vast interior, relative safety, and abundant resources, became the logical solution. By the war’s end, America would host over 500 POW camps, holding more than 425,000 enemy combatants. Camp Ewing, near Liberal, was one such installation, a significant cog in this intricate, often overlooked, wartime machinery.

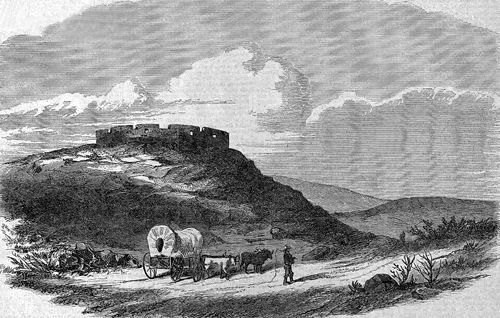

Liberal, Kansas, was chosen for several practical reasons. Its isolation offered security, far from coastal areas and potential escape routes. The flat terrain was ideal for rapid construction, and perhaps most importantly, it was strategically located near the Liberal Army Airfield, a crucial training ground for B-24 bomber crews. The camp was activated in 1943, initially designed to house up to 3,000 prisoners, though its population fluctuated, at times exceeding that number. It was a self-contained city, complete with barracks, mess halls, a hospital, recreational facilities, and guard towers, all encircled by barbed wire fences.

For the residents of Liberal and surrounding communities, the arrival of thousands of enemy soldiers was a profound culture shock. America had been drawn into the war by the attack on Pearl Harbor and the aggressive expansion of the Axis. Propaganda painted a clear picture of the enemy. To suddenly have these "enemies" in their midst, not as invaders but as prisoners, often young men barely older than their own sons fighting overseas, was a jarring experience. Initial apprehension and suspicion were natural, even expected. Local newspapers, while reporting on the camp, sometimes reflected this unease, though always within the bounds of wartime censorship and national unity.

Yet, what transpired within and around Camp Ewing was, in many ways, a testament to American values and the adherence to international law. The United States was a signatory to the Geneva Convention of 1929, which outlined the humane treatment of POWs. This meant providing adequate food, shelter, medical care, and the opportunity for meaningful labor, all under the watchful eye of the International Red Cross. Prisoners at Camp Ewing were paid 80 cents a day in scrip for their labor, which they could use at the camp’s canteen for cigarettes, toiletries, or snacks. They were allowed to wear their uniforms (though insignia were often removed), participate in religious services, and even organize cultural and educational activities.

Life inside Camp Ewing was far from luxurious, but it was generally orderly and, by wartime standards, humane. The prisoners, mostly German and some Italian, came from diverse backgrounds – farmers, factory workers, students, and professionals. To combat boredom and contribute to the war effort (indirectly, as per the Geneva Convention’s rules against direct war-related labor), they were put to work. A common sight in southwest Kansas during those years was groups of German POWs, under armed guard, heading out to local farms. They picked cotton, harvested wheat, thinned sugar beets, and helped with other agricultural tasks that American labor shortages, due to men being overseas, had made critical.

"We were short-handed, desperately short-handed," recalled Agnes Miller, whose family farm near Liberal relied on the POWs for their sugar beet harvest. "At first, we were a bit scared. They were the enemy, after all. But they were just boys, really. And they worked hard. We’d give them extra water, sometimes a sandwich. They were polite." This sentiment, echoed by many rural Kansans, highlights a fascinating aspect of the POW experience: the gradual breakdown of "enemy" stereotypes through direct, if supervised, interaction.

Beyond labor, the prisoners created their own vibrant, if confined, community. They organized soccer teams, staged plays, formed orchestras, and took classes. Many learned English, often teaching their guards German in return. Some even started small businesses within the camp, using their artistic or crafting skills. These activities served not only as morale boosters but also as a way for the prisoners to maintain a sense of dignity and purpose in an otherwise powerless situation. There were even instances of escape attempts, though these were generally short-lived and often more about curiosity than genuine malice. The vast, empty plains of Kansas, after all, offered few places to hide for a foreigner without local knowledge or resources. Most escapees were quickly apprehended, often found asking for directions or a meal at a nearby farmhouse.

The experience at Camp Ewing, and similar camps across the US, was not without its complexities. There were instances of internal divisions among prisoners, particularly between ardent Nazis and those who were disillusioned with the regime or simply conscripted. American authorities were aware of these tensions and tried to manage them, sometimes separating groups to prevent conflict or propaganda efforts. Yet, overall, the atmosphere was one of pragmatic coexistence.

As the war drew to a close in 1945, the fate of the prisoners became a priority. Repatriation was a massive undertaking. The men of Camp Ewing, having spent years in the heart of America, were gradually shipped back to Europe. For many, their time in Kansas had been transformative. They had seen a different side of America, one that was not solely defined by the battlefields. They had experienced a level of freedom and humane treatment that often surprised them, especially those who had been fed Nazi propaganda demonizing the Allied nations. Some left with a deep appreciation for the country that had held them captive, carrying memories of kindness and the vast, open skies of Kansas.

The physical remnants of Camp Ewing are scarce today. Like many temporary wartime installations, it was dismantled after the war, its buildings sold off or repurposed, the land returned to agricultural use. The wind that sweeps across the Kansas prairie now whispers over fields where barracks once stood, where German and Italian voices once echoed. However, the legacy of Camp Ewing endures in local history archives, in the fading photographs, and in the oral histories of those who lived through that extraordinary time.

The Mid-America Air Museum in Liberal, for instance, dedicates a section to the area’s WWII history, including the POW camp. Local historical societies keep the memory alive, ensuring that this unique chapter is not forgotten. The story of Camp Ewing serves as a powerful reminder of the paradoxes of war: how humanity can emerge even amidst conflict, how perceived enemies can find common ground, and how a quiet corner of America became an unexpected crucible of international relations.

In an era of global conflict, where the treatment of prisoners of war remains a critical measure of a nation’s character, Camp Ewing stands as a quiet testament to America’s commitment to the Geneva Convention. It underscores the belief that even in wartime, there are lines that must not be crossed, and that respect for human dignity, even for the enemy, is paramount. The image of Axis soldiers working alongside American farmers in the Kansas sun is more than just a historical footnote; it is a profound illustration of a nation upholding its values, even in the most challenging of circumstances, turning a wartime necessity into an unexpected, enduring lesson in humanity. The silent plains of Kansas, once home to an unlikely oasis, continue to hold these stories, etched into the very soil, for those who care to listen.