The Unquiet Fourth: Unearthing the Fury of Bates Battle, Wyoming

On a scorching July 4th, 1874, as much of America celebrated its independence with parades and picnics, a different kind of fire ignited in the rugged heart of Wyoming Territory. Here, amidst the sagebrush and rolling hills near present-day Bates Creek, a desperate and brutal clash unfolded – a battle for land, survival, and the very soul of the American West. This was the Bates Battle, a lesser-known but pivotal engagement that pitted the U.S. Cavalry against a formidable alliance of Arapaho, Lakota (Sioux), and Cheyenne warriors, etching a bloody footnote into the annals of a nation still defining itself.

Often overshadowed by the more dramatic narratives of Little Bighorn or Wounded Knee, the Bates Battle offers a microcosm of the larger, relentless conflict that defined the Indian Wars. It was a confrontation born of broken treaties, manifest destiny, and the unyielding will of indigenous peoples to defend their ancestral lands against an ever-advancing tide of settlers, prospectors, and military might.

A Territory in Flux: The Pre-Battle Landscape

The 1870s were a cauldron of conflict in the American West. The ink on the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie, which purportedly guaranteed vast tracts of land to the Lakota and their allies, including the Powder River Country, was barely dry. Yet, the relentless push westward continued unabated. Gold discoveries in the Black Hills, the construction of railroads, and the insatiable demand for land fueled an almost constant state of tension and skirmish. For the indigenous nations, this era was one of increasing desperation. Their traditional hunting grounds were shrinking, their way of life was under assault, and the promise of peace had proven to be a fragile illusion.

Wyoming, then a territory, was a strategic crossroads. Its vast plains and mountains were rich in resources and crucial for westward expansion. The U.S. Army was tasked with protecting these interests – guarding wagon roads, suppressing perceived threats to settlers, and generally asserting federal authority over the contested lands. It was into this volatile environment that Captain Alfred E. Bates and his Company B of the 2nd U.S. Cavalry found themselves operating.

Captain Bates, a seasoned veteran, was part of a larger expedition led by Major Richard I. Dodge. Their mission was ostensibly to explore and survey potential routes for a new wagon road connecting the Union Pacific Railroad to the rich timberlands of the Wind River Mountains and the nascent mining camps further north. This task, however, inevitably placed them on a collision course with the Northern Arapaho, Lakota, and Cheyenne, who viewed such incursions as direct violations of their territorial rights and a prelude to further settlement.

The Gathering Storm: Opposing Forces

Captain Bates’s command, consisting of approximately 40 troopers, was a small but well-equipped unit. They were mounted on sturdy cavalry horses, armed with the standard-issue Springfield Trapdoor rifles – powerful, single-shot weapons that offered a significant advantage in range and accuracy over most indigenous firearms, though many warriors were increasingly acquiring modern rifles. Their mission was one of reconnaissance and protection, but in the hostile environment of the Powder River Country, every patrol carried the risk of engagement.

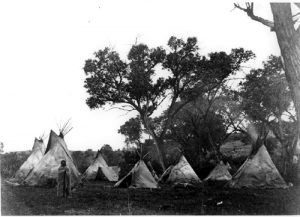

Opposing them was a formidable alliance of warriors. Led by Chief Black Coal of the Northern Arapaho, with support from Lakota and Cheyenne allies, their numbers are estimated to have ranged from 100 to perhaps as many as 200. These were not undisciplined fighters; they were skilled horsemen, expert trackers, and master tacticians, intimately familiar with the terrain. Their motivation was clear: to halt the advance of the white soldiers and protect their people, their hunting grounds, and their very existence. For them, this was not merely a battle for territory, but a sacred duty.

The Fourth of July Ambush

The stage was set on that fateful July 4th. Bates’s company, having detached from Major Dodge’s main force, was moving through the rugged country near what would later be named Bates Creek. The air was thick with the scent of sagebrush and the oppressive heat of a high-desert summer. The troopers were vigilant, but the indigenous warriors, masters of concealment, had been tracking them for some time.

As the cavalry rode along a narrow valley, the stillness shattered. From the bluffs and ravines above, a fusillade of gunfire and arrows erupted. It was a classic ambush, designed to disorient and overwhelm the smaller cavalry unit. The warriors, utilizing the broken terrain to their advantage, poured fire down on the unsuspecting soldiers.

Captain Bates, despite the surprise, reacted swiftly. A seasoned officer, he understood the critical importance of gaining the high ground and maintaining formation. He immediately ordered his men to dismount and return fire, seeking cover where they could. The fight quickly devolved into a desperate, close-quarters engagement. The sounds of rifle shots mingled with the thud of arrows, the shouts of men, and the war cries of the warriors.

A Desperate Stand: The Battle Unfolds

The terrain played a crucial role. The warriors, initially holding the higher ground, were able to inflict casualties on the exposed cavalrymen. However, the superior firepower and discipline of the U.S. Army began to tell. Bates rallied his men, leading a counter-attack up the slopes, determined to dislodge the ambushers. This was not a static fight; it was a running battle, with skirmishes erupting across the rugged landscape.

One particularly intense phase of the battle saw hand-to-hand combat. Accounts speak of the bravery on both sides – troopers fighting desperately to hold their ground, and warriors exhibiting incredible courage as they charged the fortified positions, armed with bows, lances, and a growing number of firearms. Chief Black Coal himself was a prominent figure, leading from the front, inspiring his warriors with his defiance.

The fighting raged for several hours under the relentless summer sun. The cavalry, despite being outnumbered, eventually managed to dislodge the warriors from their key positions. The Springfield rifles, capable of firing accurately at longer ranges, provided a decisive advantage against many of the warriors’ older firearms and traditional weapons. The sheer volume of fire and the methodical advance of the disciplined soldiers began to take their toll.

As the afternoon wore on, the warriors, having sustained significant casualties, began to withdraw. Their objective was not necessarily to annihilate the cavalry but to deter them, to make it clear that this land was defended, and that further incursions would come at a heavy price. The withdrawal was tactical, not a rout, but it marked the end of the immediate engagement.

Aftermath and Casualties

When the smoke cleared, the cost of the battle was evident. The U.S. Cavalry suffered relatively light casualties, with two troopers killed and a handful wounded. This low number was a testament to their training, firepower, and Captain Bates’s leadership.

For the allied tribes, however, the losses were much heavier. While exact numbers are difficult to ascertain due to the nature of indigenous warfare (where warriors often carried off their dead and wounded), estimates suggest between 25 to 30 warriors were killed, and many more wounded. The Arapaho, in particular, bore the brunt of these losses, including several prominent members of their community. This was a significant blow to their fighting strength and morale.

Captain Bates, despite the tactical victory, knew he was in hostile territory. After tending to his wounded and burying his dead, he carefully withdrew his company, eventually rejoining Major Dodge’s main force. The immediate objective of the road survey was temporarily put on hold, but the broader conflict continued unabated.

A Footnote in History, A Legacy of Conflict

The Bates Battle, fought on the nation’s birthday, served as a stark reminder of the true cost of westward expansion. It was a clash of two irreconcilable forces: the relentless march of American settlement and the desperate struggle of indigenous peoples to preserve their way of life.

Why is it less known than other battles? Several factors contribute. It was a relatively small-scale engagement compared to the epic clashes that would follow, such as the Battle of the Little Bighorn just two years later. There were no famous generals like Custer involved, no grand strategic implications that reshaped the entire war. Yet, its significance lies in its typicality. The Bates Battle was one of hundreds of such skirmishes, ambushes, and fights that collectively defined the Indian Wars. It embodied the courage, the desperation, and the tragedy of that era for both sides.

For the Arapaho, the battle was a painful but defiant stand. It demonstrated their unwavering commitment to their lands, even in the face of overwhelming odds. For the U.S. Army, it was a successful engagement, but one that highlighted the immense challenge of pacifying a vast territory inhabited by resilient and determined indigenous nations.

Today, a historical marker near Bates Creek commemorates the battle, a quiet sentinel in the vast Wyoming landscape. It invites reflection on a complex past, reminding us that history is rarely simple, and that even seemingly minor events can carry profound weight. The Bates Battle, though fought in the shadow of larger narratives, remains a powerful testament to the bravery and sacrifice of all those who fought and died on the frontier. It is a reminder that the narrative of America’s expansion is not a simple tale of triumph, but a complex tapestry woven with courage and tragedy, ambition and resistance, the echoes of which still resonate in the unquiet heart of the American West.