The Unraveling: How the Kansas-Nebraska Act Ignited America’s Civil War

In the annals of American history, few legislative acts cast as long and ominous a shadow as the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854. Conceived with ambitions of westward expansion and national unity, it instead tore open the fragile compromises holding the Union together, plunging the nation into a bloody prelude to its inevitable civil war. This single piece of legislation, a masterpiece of political maneuvering by its architect, Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois, inadvertently became the detonator for the deepest conflict in American history.

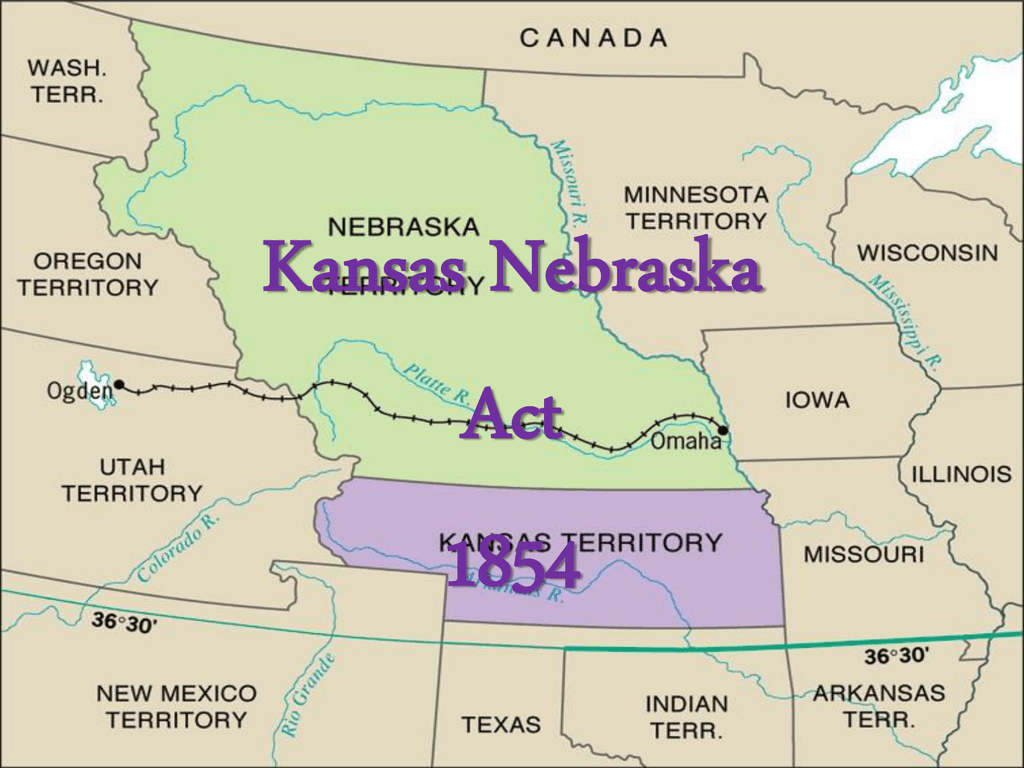

At its heart, the Kansas-Nebraska Act was a legislative gamble predicated on the alluring, yet ultimately disastrous, principle of "popular sovereignty." Douglas, a diminutive but titanic figure known as the "Little Giant," envisioned a vast transcontinental railroad connecting the East to the burgeoning West, with Chicago as its eastern hub. To achieve this, he needed to organize the immense unorganized territory west of Missouri and Iowa. This land, known as the Nebraska Territory, lay north of the 36°30′ parallel, a line established by the venerable Missouri Compromise of 1820, which had prohibited slavery in all new territories north of that latitude, save for Missouri itself.

The Weight of a Compromise

The Missouri Compromise had been a cornerstone of sectional peace for over three decades. It was a delicate balance, acknowledging slavery where it existed but limiting its expansion. For many, particularly in the North, it was considered a sacred, almost constitutional, agreement. To touch it was to invite catastrophe.

However, the political landscape had shifted dramatically since 1820. The Mexican-American War had added vast new territories to the United States, reigniting the explosive debate over slavery’s expansion. The Compromise of 1850 had temporarily quelled these tensions, but it had also introduced the concept of popular sovereignty to the territories acquired from Mexico, allowing residents there to decide on the slavery question for themselves. This precedent, though applied to different lands, would become Douglas’s weapon.

Douglas, a shrewd politician with an eye on the presidency, knew that organizing the Nebraska territory under the Missouri Compromise’s anti-slavery mandate would face fierce opposition from Southern senators. They saw it as denying them access to new lands for their "peculiar institution." To win their support and clear the path for his railroad, Douglas made a fateful concession: he proposed that the principle of popular sovereignty, previously applied only to the Mexican Cession, should also apply to the Nebraska territory.

The Fatal Flaw: Popular Sovereignty

Initially, Douglas’s bill proposed organizing a single Nebraska Territory. But Southern senators, led by Missouri’s David Rice Atchison, demanded more. They wanted a clear path for slavery into the region and insisted on the explicit repeal of the Missouri Compromise line. Under pressure, Douglas revised his bill. The new version would divide the territory into two: Kansas to the south, bordering slave-state Missouri, and Nebraska to the north. Crucially, it stated that the Missouri Compromise was "inoperative and void," effectively opening both territories to the possibility of slavery if their residents voted for it.

The concept of popular sovereignty, or "squatter sovereignty" as its critics derisively called it, sounded inherently democratic. "The great principle of self-government," Douglas declared, was that "every people ought to have the right to form and regulate their own domestic institutions in their own way." He genuinely believed this approach would remove the contentious issue of slavery from Congress, allowing local populations to decide, thus promoting national unity. He severely underestimated the moral outrage and fierce determination of both sides.

A Storm in Congress

The introduction of the Kansas-Nebraska Act in January 1854 unleashed a political firestorm. Northern Whigs and anti-slavery Democrats were aghast. They saw it as a betrayal, a cynical capitulation to Southern demands, and a moral abomination that opened the floodgates for slavery’s expansion. Horace Greeley, editor of the New York Tribune, famously declared it "an atrocious plot" and called for every freeman to resist it.

The debates in Congress were venomous, stretching for months. Opponents, including senators like Salmon P. Chase of Ohio and Charles Sumner of Massachusetts, lambasted the bill as a "gross violation of a sacred pledge." Sumner, a fiery abolitionist, delivered impassioned speeches condemning the bill, warning that it would "let loose the demon of discord." Southern leaders, conversely, championed the bill as a matter of states’ rights and equal access to territories.

Despite the fierce opposition, Douglas, with his formidable political skills and the support of President Franklin Pierce, managed to push the bill through. It passed the Senate by a vote of 37 to 14 and, after a grueling debate, the House of Representatives by 113 to 100. President Pierce signed it into law on May 30, 1854. The Missouri Compromise, a pillar of American stability, was dead.

"Bleeding Kansas": The Unfolding Horror

The ink on the Kansas-Nebraska Act was barely dry before its catastrophic consequences began to manifest. The idea that residents would simply "vote" on slavery proved a dangerous fantasy. Instead, Kansas became a battleground, a bloody proving ground for the coming Civil War.

Both pro-slavery and anti-slavery factions immediately recognized the stakes. Organized groups, funded by both Northern abolitionist societies (like the New England Emigrant Aid Company) and Southern pro-slavery militias, poured into Kansas. These "emigrants" were often armed and determined to sway the vote, by force if necessary.

The initial elections were rife with fraud and intimidation. In November 1854 and March 1855, thousands of "Border Ruffians" from Missouri, armed and often drunk, illegally crossed the border to cast ballots, ensuring overwhelming pro-slavery majorities. These fraudulent elections led to the establishment of a pro-slavery territorial legislature in Lecompton, which quickly enacted draconian slave codes.

In response, free-staters, refusing to recognize the legitimacy of the Lecompton government, formed their own parallel government in Topeka. Kansas now had two rival governments, two constitutions, and two sets of laws, each claiming legitimacy. The stage was set for violence.

The ensuing years, from 1854 to roughly 1859, became known as "Bleeding Kansas." The territory descended into a miniature civil war. The first major eruption occurred in May 1856, when a pro-slavery posse sacked the free-state town of Lawrence, destroying printing presses and burning buildings. The incident, though relatively bloodless, sparked outrage across the North.

Just days later, the radical abolitionist John Brown, incensed by the Sack of Lawrence and the earlier assault on Senator Charles Sumner (who was brutally beaten with a cane on the Senate floor by Congressman Preston Brooks for his anti-slavery speech, "The Crime Against Kansas"), retaliated. Brown, with a small band of followers, dragged five pro-slavery settlers from their homes along Pottawatomie Creek and hacked them to death with broadswords. This act of cold-blooded murder ignited a cycle of revenge killings, ambushes, and skirmishes that claimed an estimated 200 lives over the next few years. Farms were burned, families terrorized, and the rule of law collapsed.

The Political Earthquake and the Birth of a Party

The fallout from the Kansas-Nebraska Act extended far beyond the prairies of Kansas. It fundamentally reshaped the American political landscape.

Firstly, it utterly destroyed the Whig Party. Already weakened by internal divisions over slavery, the act split the party irrevocably along sectional lines. Northern Whigs, outraged by the repeal of the Missouri Compromise, abandoned the party, while Southern Whigs drifted towards the Democrats. By 1856, the Whig Party had effectively ceased to exist.

Secondly, it fractured the Democratic Party. While Douglas managed to secure its passage, the act alienated a significant portion of Northern Democrats, who felt betrayed by their party’s embrace of slavery expansion. This division would only deepen in the years to come, fatally weakening the party on the eve of the Civil War.

Most significantly, the Kansas-Nebraska Act gave birth to the Republican Party. Formed in 1854 as a direct response to the act, the new party coalesced around a core platform: opposition to the extension of slavery into the new territories. It drew together former Whigs, Free-Soilers, and disaffected Northern Democrats. Abraham Lincoln, a former Whig congressman from Illinois, was among its earliest and most eloquent proponents, famously condemning the act as a "great wrong." He understood that the act had not merely opened new territories to slavery but had also deeply unsettled the moral conscience of the nation.

The Irreversible Path to Disunion

The chaos in Kansas and the radical shifts in national politics were not isolated incidents; they were interconnected tremors preceding a massive earthquake. The Kansas-Nebraska Act inadvertently fueled a series of events that accelerated the nation’s descent into civil war.

The Dred Scott v. Sandford Supreme Court decision of 1857, which declared that Congress had no power to prohibit slavery in the territories (thus making popular sovereignty itself constitutionally questionable) and that black people, free or enslaved, were not citizens, further inflamed sectional tensions. It seemed to confirm Northern fears that the entire federal government was conspiring to expand slavery.

The Lincoln-Douglas debates of 1858, ostensibly for an Illinois Senate seat, became a national platform to discuss the very issues raised by the Kansas-Nebraska Act. Lincoln skillfully exposed the moral bankruptcy of popular sovereignty, arguing that a nation divided "cannot stand." While Douglas won the Senate race, Lincoln’s powerful articulation of the anti-slavery cause elevated him to national prominence, setting the stage for his presidential bid in 1860.

In the end, the Kansas-Nebraska Act, a legislative maneuver designed to foster compromise and facilitate westward expansion, achieved precisely the opposite. It nullified a sacred agreement, ignited a brutal proxy war in Kansas, shattered the existing political party system, and gave rise to a powerful new anti-slavery party. It exposed the irreconcilable differences between North and South over the future of slavery, pushing the nation past the point of no return. Stephen Douglas, the "Little Giant," had sought to untangle a knot but instead cut the cord holding the Union together, ushering in an era of unprecedented conflict and ultimately, the bloodiest war in American history. The act remains a stark reminder that even well-intentioned political compromises, when they ignore fundamental moral divisions, can unleash forces far beyond their architects’ control.