The Unstoppable Engine: How the Industrial Revolution Forged Our Modern World

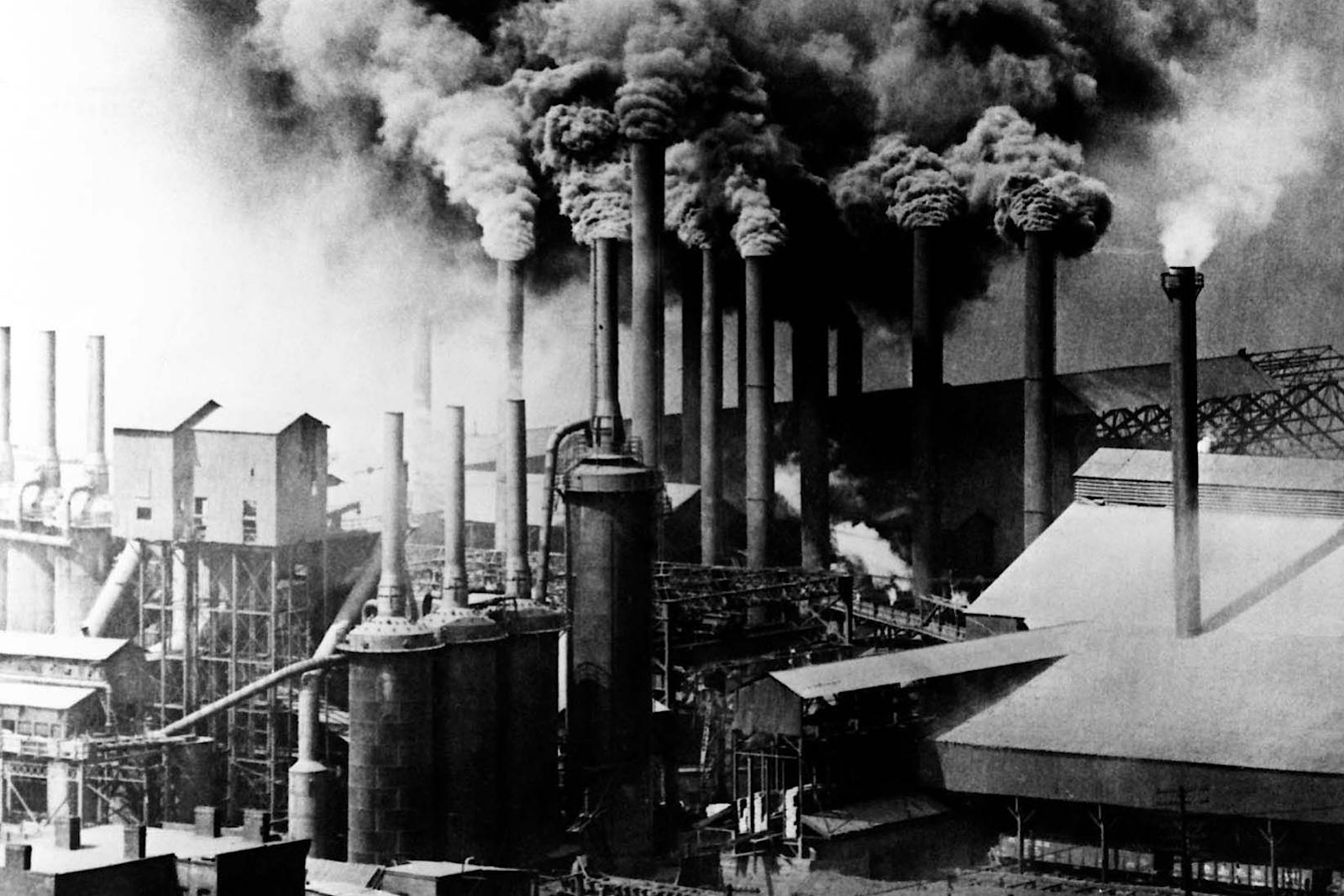

Imagine a world powered not by muscle or wind, but by the relentless hiss and thrum of steam. A world where goods, once painstakingly crafted by hand, now pour from colossal factories. A landscape transformed by smoke-stack silhouettes and iron arteries of rail. This wasn’t a slow evolution; it was a seismic shift, a revolution that ripped through the fabric of human existence and irrevocably forged the modern world we inhabit today. This was the Industrial Revolution, an era that began in the unassuming workshops and coalfields of 18th-century Britain, unleashing forces that continue to shape our economies, societies, and even our planet.

Before this unprecedented upheaval, life for most was agrarian, localized, and largely unchanging across generations. Villages were self-sufficient, producing what they consumed. Travel was slow and arduous. Information spread at the pace of a horse. It was a world of finite resources and human limitations. Then came the spark.

Britain’s Crucible: The Perfect Storm

Why Britain? The question has long fascinated historians, and the answer lies in a fortuitous convergence of factors. Firstly, Britain possessed abundant natural resources: vast reserves of coal and iron, the very fuel and sinew of industrialization. Its island geography, combined with a robust network of rivers and canals, provided efficient transport for raw materials and finished goods.

Politically, Britain enjoyed a period of relative stability, fostering an environment where innovation and investment could flourish. Unlike many continental European nations plagued by internal strife, the British state was stable enough to protect property rights and enforce contracts, crucial for nascent industries. Furthermore, a burgeoning colonial empire provided not only raw materials like cotton but also captive markets for manufactured goods.

Perhaps most critically, there was a culture of scientific inquiry and practical ingenuity. The Enlightenment had fostered a spirit of rational investigation, and while many early inventors were not formally trained scientists, they were brilliant tinkerers driven by practical problems. This fertile ground was about to bear extraordinary fruit.

The Weave of Innovation: From Cottage to Factory

The first industry to be truly revolutionized was textiles. For centuries, cloth production was a "cottage industry," with spinning and weaving done by hand in homes. But demand for cloth, particularly cotton, was soaring. The bottleneck was spinning. A single weaver could outpace several spinners.

Enter a series of ingenious inventions. In 1764, James Hargreaves, a weaver, invented the Spinning Jenny, allowing one worker to operate multiple spindles simultaneously. This was quickly followed by Richard Arkwright’s Water Frame (1769), which used water power to produce stronger thread, and Samuel Crompton’s Mule (1779), which combined the best features of both, creating fine, strong yarn. These machines, too large and expensive for homes, necessitated purpose-built factories, often located near rivers for water power.

But the true game-changer was the Power Loom, perfected by Edmund Cartwright in 1785. While initially slow to adopt, its eventual widespread use mechanized weaving, transforming what was once skilled manual labor into a machine-driven process. The sheer scale was astonishing: by 1835, a single power loom operator could produce 3.5 times as much cloth as a handloom weaver. This explosion in textile production drove down prices, making clothing accessible to the masses and fueling global trade.

An interesting footnote to this textile revolution is its connection to another continent. The demand for raw cotton spurred the growth of plantations in the American South, and Eli Whitney’s Cotton Gin (1793), which efficiently separated cotton fibers from seeds, dramatically increased the profitability of cotton production. Tragically, this innovation inadvertently entrenched and expanded the institution of slavery in the United States, linking the progress of industrialization in one part of the world to immense human suffering in another.

The Age of Steam: The True Game-Changer

While water power was effective, it tethered factories to rivers. The real breakthrough, the invention that untethered industry and allowed it to spread, was the steam engine. Early rudimentary steam engines, like Thomas Newcomen’s atmospheric engine (1712), were used primarily to pump water out of mines. They were inefficient giants.

It was James Watt, a Scottish instrument maker, who truly transformed steam power. Tasked with repairing a Newcomen engine in the 1760s, Watt identified its inefficiencies and, over several years, developed a separate condenser and other improvements. His patented rotary steam engine (1781) was far more efficient and, crucially, could drive machinery of all kinds, not just pumps.

Watt’s engine was the heart of the Industrial Revolution. It could power textile mills, forge iron, and eventually, propel trains and ships. No longer reliant on fickle winds or flowing water, factories could be built anywhere coal was available. The "Age of Steam" had arrived, providing unprecedented levels of reliable, concentrated power.

Iron, Coal, and Steel: Building the Future

The steam engine’s appetite for fuel drove the expansion of coal mining. Deeper mines required better pumps and stronger lifting equipment, further stimulating innovation. Coal, in turn, was essential for the iron industry. Abraham Darby’s earlier innovation (1709) of smelting iron with coke (a purified form of coal) instead of charcoal allowed for larger-scale production. Later, Henry Cort’s puddling and rolling process (1784) produced stronger, more malleable wrought iron.

This better iron was crucial for building more efficient steam engines, stronger machines, and the infrastructure of the new industrial age. Bridges, buildings, and eventually, the railways that would crisscross the land, all depended on this foundational material. Much later, the Bessemer process (1856) would make steel production cheap and efficient, ushering in the "Second Industrial Revolution" and enabling even grander structures and machines.

Connecting the World: The Railway Revolution

Perhaps nothing symbolized the Industrial Revolution’s relentless momentum more than the railway. Early railways, or "wagonways," had existed for moving coal in mines, using horses. But the application of steam power to locomotion was transformative. Richard Trevithick built the first full-scale working railway steam locomotive in 1804, but it was George Stephenson’s "Rocket" (1829), winning the Rainhill Trials, that truly launched the railway age.

Suddenly, goods and people could be transported across vast distances with unprecedented speed and volume. Raw materials could reach factories, finished goods could reach markets, and people could travel for work or leisure. The railways shrunk distances, fostered national markets, and spurred further industrial growth by demanding vast quantities of iron, coal, and labor. By 1850, Britain had over 6,000 miles of railway tracks. Steamships, similarly, revolutionized oceanic transport, connecting global markets as never before.

The Human Cost and Societal Transformation

While the Industrial Revolution brought unprecedented wealth and technological advancement, its immediate human cost was immense. Rapid urbanization saw millions flock from rural areas to burgeoning industrial cities like Manchester and Birmingham, which swelled beyond recognition. These cities were often ill-equipped to handle the influx, leading to overcrowding, squalor, and rampant disease.

Working conditions in factories and mines were brutal. Long hours (12-16 hours a day, six days a week) were common, pay was meager, and safety was non-existent. Children as young as five were employed in dangerous conditions, often for their small stature to navigate machinery or narrow mine shafts. Accounts of industrial life from the era are chilling. Friedrich Engels, in The Condition of the Working Class in England (1845), painted a stark picture of poverty, disease, and exploitation. The "Great Stink" of 1858 in London, caused by the untreated sewage in the River Thames, was a stark illustration of the environmental and public health crises that industrialization wrought.

A new social order emerged: a powerful industrialist class at the top, a growing middle class of managers and professionals, and a vast, often impoverished, industrial working class – the proletariat. The stark inequalities and harsh realities of industrial capitalism gave rise to new political and economic ideologies, including socialism and communism, most famously articulated by Karl Marx and Engels. Their Communist Manifesto (1848) was a direct response to the perceived injustices of the industrial system.

An Unfolding Legacy

By the mid-19th century, the Industrial Revolution had spread beyond Britain, taking root in Belgium, France, Germany, and the United States. It continued to evolve, leading to a "Second Industrial Revolution" from the late 19th century, characterized by new sources of energy (electricity, oil), new industries (chemicals, steel, internal combustion engine), and new forms of mass production (assembly lines).

The legacy of the Industrial Revolution is the world we inhabit. It gave us mass production, global trade, rapid transportation, and communication (telegraph, telephone). It lifted countless millions out of subsistence living and led to an overall rise in living standards, though often at a steep initial price for many. It created the foundations of modern capitalism and consumerism.

Yet, its legacy also includes profound challenges: environmental degradation, social inequality, and the relentless pressure of technological change. The question of how to balance economic progress with human well-being and environmental sustainability remains a central dilemma of our time, a direct inheritance from the choices made during that pivotal era.

The Industrial Revolution was not a singular event but an ongoing process, a testament to human ingenuity and its often-unforeseen consequences. From the whirring spindles of a cotton mill to the roaring furnaces of a steelworks, it set in motion an unstoppable engine of progress and disruption that continues to redefine what it means to be human in an ever-accelerating world. We are, in essence, still living in the revolution it began.