The Unsung Apostles of the American Frontier: Pioneer Preachers and the Forging of a Nation’s Soul

Picture a solitary figure, dust-caked and weary, astride a horse that knows the winding paths of the wilderness better than any map. He carries no weapon, no great fortune, only a Bible, a hymnal, and an unshakeable conviction. This is the iconic image of the pioneer preacher, a spiritual vanguard who braved the untamed American frontier, not with a rifle and a plow, but with a sermon and a prayer. These were the circuit riders, the evangelists, the forgotten giants who, in the 18th and 19th centuries, played a foundational role not just in shaping America’s religious landscape, but in forging its very identity.

Their story is one of unparalleled hardship, fierce dedication, and profound impact. As settlers pushed westward, leaving behind the established churches and social structures of the East, a spiritual vacuum emerged. Life on the frontier was brutal: isolated, dangerous, and often devoid of formal education or moral guidance. Into this void stepped the pioneer preachers, men (and occasionally women, though far less recognized in formal roles) who felt a divine call to bring salvation, community, and a sense of order to a chaotic new world.

The Call to the Wilderness: A Spiritual Imperative

The period following the American Revolution saw rapid expansion and a significant religious revival known as the Second Great Awakening. This era, roughly from the 1790s to the 1840s, was characterized by widespread evangelical fervor and a deeply democratic impulse in religious practice. Unlike the more structured, often hierarchical denominations of Europe, American frontier religion was dynamic, personal, and accessible. It resonated with the independent spirit of the settlers.

The most famous of these spiritual trailblazers were the Methodist circuit riders, though Baptists, Presbyterians, and other denominations also sent their ministers into the wild. What drove these men to abandon comfort, family, and safety for a life of relentless travel and often meager reward? It was, unequivocally, a profound sense of divine calling. They believed, with every fiber of their being, that souls were in peril and that they were God’s chosen instruments to deliver the message of salvation.

As historian Nathan O. Hatch noted in his seminal work, The Democratization of American Christianity, these preachers were not just religious figures; they were "cultural heroes who supplied a spiritual and moral framework for a sprawling and diverse society." They spoke a language that resonated with the common person, bypassing theological complexities for direct, emotional appeals to the heart.

Enduring Hardship: A Life on Horseback

The life of a pioneer preacher was not for the faint of heart. They traversed vast distances on horseback, often covering hundreds, even thousands of miles annually, regardless of weather. Swamps, dense forests, raging rivers, and treacherous mountain passes were their daily commute. They faced wild animals, disease, hunger, and the constant threat of injury or death. Lodging was often primitive, consisting of rough cabins, lean-tos, or simply the open sky. Meals were sparse and basic.

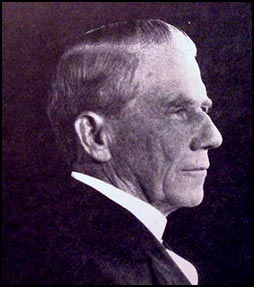

Francis Asbury, the "Father of American Methodism," is perhaps the most iconic example of this endurance. Arriving in America from England in 1771, he dedicated his life to organizing and leading the Methodist movement. Over 45 years, he rode an astonishing estimated 300,000 miles on horseback – a distance equivalent to circling the globe more than ten times. He preached an estimated 16,000 sermons, held countless meetings, and established churches and circuits across the nascent nation. His journals reveal a man driven by an almost superhuman resolve, enduring sickness, pain, and constant travel. One poignant entry captures his spirit: "Lord, we are here, and here we mean to stay."

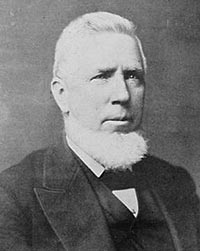

Peter Cartwright, another legendary figure, vividly described the physical demands in his Autobiography of Peter Cartwright, The Backwoods Preacher: "My circuit was four hundred miles round, and I had to preach every day, and very often twice a day. I had to swim creeks, and sometimes my horse would get bogged, and I would have to get off and wade. I suffered greatly from cold, hunger, and exposure." His account is a raw, unvarnished look at the reality of the frontier ministry, far removed from any romanticized notions.

The Camp Meeting Phenomenon: Igniting the Spirit

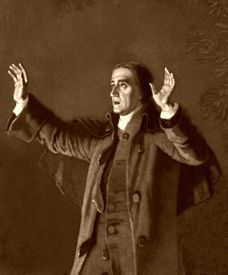

Perhaps the most distinctive and impactful method of the pioneer preachers was the camp meeting. These multi-day religious revivals, held in forest clearings, brought together thousands of settlers from miles around. They were part social gathering, part spiritual catharsis, and part sheer spectacle. Families would travel for days, camping out in tents and wagons, eager for human connection as much as divine inspiration.

The Cane Ridge Revival in Kentucky in 1801 is often cited as the prototype, drawing an estimated 10,000 to 25,000 people – a staggering number for the time and place. Preachers from various denominations would take turns delivering fiery sermons from makeshift pulpits. The atmosphere was electric, charged with emotion. People would shout, weep, dance, and fall into trance-like states, experiencing what they believed to be direct encounters with the Holy Spirit.

These meetings provided a powerful sense of community and shared experience in an otherwise fragmented world. They offered emotional release, moral guidance, and a renewed sense of purpose. For many, they were the only form of entertainment, news, and social interaction available. The raw, uninhibited nature of these revivals contrasted sharply with the more formal worship of the East, cementing a uniquely American style of evangelical Christianity.

More Than Preachers: Nation Builders and Social Reformers

The influence of pioneer preachers extended far beyond spiritual conversion. They were, in many ways, the unacknowledged nation-builders of the frontier.

- Community Architects: They established churches, which often served as the first public buildings in a new settlement. These churches became centers for social life, education, and mutual aid. They provided a moral compass and helped instill a sense of order and shared values in rapidly expanding communities.

- Educators: Many pioneer preachers were passionate advocates for education. They founded academies and colleges, seeing literacy and learning as essential for both spiritual understanding and civic virtue. Methodist institutions like Emory and Henry College, Randolph-Macon College, and McKendree University trace their roots to this era.

- Social Reformers: While their primary focus was on individual salvation, many pioneer preachers also championed social causes. The Methodist and Baptist denominations, in particular, were early and vocal opponents of slavery, though their stances sometimes wavered under pressure in the southern states. They also spearheaded the temperance movement, advocating against alcohol abuse, which was a pervasive problem on the frontier. Peter Cartwright, for instance, was known for physically confronting drunkards and rowdies at his meetings.

- Democratic Spirit: Their emphasis on personal conversion and accessible theology resonated with the democratic ideals of the young republic. They fostered a sense that spiritual authority lay not just with an educated elite, but with any individual who felt called to preach, regardless of their social standing or formal training.

The Enduring Legacy

By the mid-19th century, the era of the lone circuit rider began to wane as towns grew, roads improved, and established churches became more common. Yet, the legacy of the pioneer preachers remains indelibly stamped on the American psyche.

Their tireless efforts laid the groundwork for the robust and diverse religious landscape of the United States. They cultivated an evangelical tradition characterized by personal experience, passionate preaching, and a strong missionary impulse that continues to shape many denominations today. They instilled a sense of moral purpose and community in a vast, wild land, helping to civilize the frontier not just physically, but spiritually.

The stories of figures like Asbury and Cartwright, with their tales of unwavering faith, incredible endurance, and direct engagement with the challenges of their time, have become part of American folklore. They embody the frontier spirit: resilience, self-reliance, and an unshakeable belief in a higher purpose.

In a modern world often characterized by cynicism and fragmentation, the dedication of these pioneer preachers offers a powerful reminder of the human capacity for devotion, sacrifice, and the enduring quest for meaning. They were, indeed, the unsung apostles who rode into the heart of a new nation, not merely spreading a faith, but helping to forge a soul. Their dust-caked Bibles and weary horses carried not just sermons, but the very seeds of American identity.